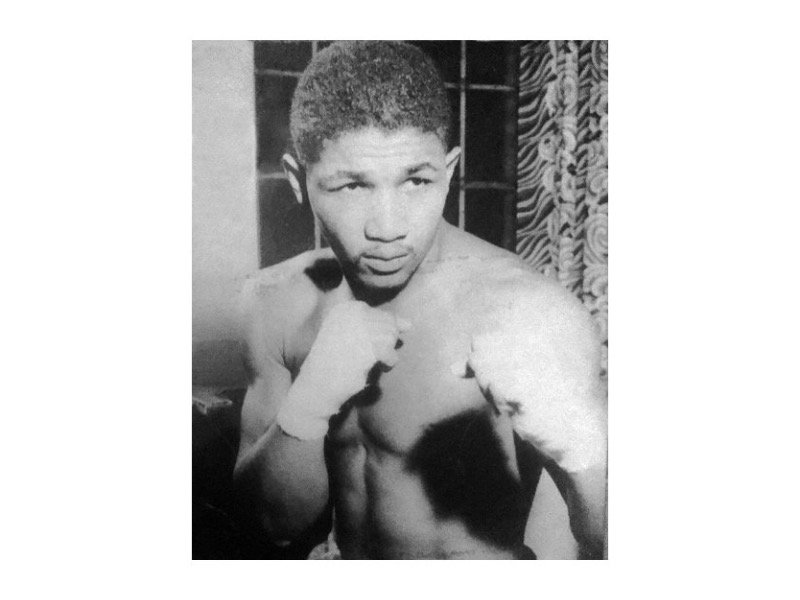

Fifty-nine years ago this month a Milwaukee heavyweight boxer called "Long John" Hubbard got what was coming to him for putting up what a newspaper called "the best fight of his career."

Three months in the House of Correction.

If he had fought in the ring with half the ferocity with which he battled six policemen in a wild street brawl that made headlines diametrically opposite the kind abounding in the local press today, Hubbard might now be in the Boxing Hall of Fame.

But the only time he lived up to his true potential in the squared circle, Hubbard was fired as a sparring partner for world champion Joe Louis in 1949 for making one of the greatest heavyweights of all time look like a chump.

Otherwise, the 6-foot-3-inch Hubbard never attained more than journeyman status in a nine-year boxing career that achieved impressive lift-off in 1942 when he won the Milwaukee Golden Gloves 175-pound championship and went as far as the semi-finals of the National Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions in Chicago.

The following year Hubbard – one of the numerous outstanding amateurs developed at the legendary Urban League gym at North 9th and West Vine Streets by former professional great Baby Joe Gans – repeated as local Golden Gloves champ and again fought his way to the semi-finals of the national tournament at Chicago Stadium, and then lost because his opponent took advantage of Hubbard's good sportsmanship.

When the bell rang to start the third and final round of the Milwaukee boxer's semi-final bout with Chicago's Reedy Evans, reported the Journal's R.G Lynch from ringside at Chicago Stadium, "As Long John reached out to touch gloves ... Evans smashed a right to the chin" which sent the Milwaukee boxer to the mat and on his way to a KO loss.

"The knockout punch was within the rules, which call for boxers to come out fighting," reported Lynch, "but the crowd of 20,624 knew it was dirty in an amateur bout and booed (Evans) until the stadium rocked. When Hubbard was able to get up the fans cheered him long and loudly."

They cheered more a month later when Hubbard, selected as an alternate on the team of Chicago Golden Gloves champions facing off against their New York City counterparts, won a decision over future pro heavyweight contender Bill Gilliam.

But after turning pro in '43, Hubbard was never more than a preliminary fighter in his own hometown, though he did headline a couple cards in Chicago. He won more than he lost (finishing in 1951 with a record of 24-12-3), but was never even close to becoming a contender for the title held by the great Louis, the immortal Brown Bomber who'd owned the heavyweight championship belt since 1937 and put it up for grabs a record 25th time when he fought Jersey Joe Walcott at Yankee Stadium in New York City on June 25, 1948.

Long John hired on as one of the champ's sparring partners at Louis' training camp at Pompton Lakes, N. J. A sparring partner for Joe Louis was a glorified shock-absorber, given room and board and paid up to $25 a round to take a beating from Joe, who never held back against his hired help.

But Louis had problems with Long John from the start. "Hubbard, a lanky 185-pounder who imitates Walcott's style expertly, proved an elusive target," wrote Whitney Martin of the AP after watching them spar on June 1.

A week later, Lynch of the Journal reported that Hubbard had been sent packing by Louis' trainer, Manny Seaman, "because he kept jabbing with his glove open and his thumb caught Louis in the eye several times."

That was news to Long John, who in response showed Lynch a column from the Newark Evening News by sports editor Willie Ratner, in which Ratner wrote: "I don't think Hubbard will be around camp for any length of time. If the heavyweight champion does not render him hors de combat within the next few workouts he is almost certain to fire the guy. If you think Walcott made Louis look bad (in their first fight, won by Louis on a highly controversial decision), you should see what Mr. Hubbard does to him." Long John's indiscretions reportedly included knocking Louis down at least once.

That was the high water mark of Hubbard's two-fisted career until 2 o'clock on the morning of Nov. 2, 1953. That's when two police patrolmen, seeing him walking on North 5th and West Juneau Streets, stopped Hubbard and demanded to know what he was doing. He refused to answer and the cops put him under arrest for vagrancy and started to pat him down, at which point Hubbard started swinging, knocking one of them out with a punch to the jaw and hitting the other one so hard in the right arm that it was paralyzed. With his good arm the officer whacked Hubbard repeatedly on the head with his billy club to no effect.

Two detectives arrived on the scene and after radioing for reinforcements waded into the fray. Their billy clubs also shattered over Hubbard's skull, but he was still swinging away – even after one of the cops pointed his gun at Hubbard's head and said if he didn't stop fighting he'd shoot – when they and three more cops finally subdued and took him into custody. Three of the policemen required medical care.

"Fighter Batters Police; Protection Drive Starts" was the front-page headline in the Journal the next day, over side-by-side stories. One was about the battle royale between Hubbard and the six cops; the other concerned Mayor Frank Zeidler's instructions to Police Chief John W. Polcyn "to take whatever steps are necessary to protect policemen against assault by belligerent men whom they have arrested."

Jet Magazine, the national African-American weekly, reported the incident under the headline, "Louis's Ex-Sparring Mate Stages 1-Man Riot."

R.G. Lynch added fuel to the fire when he weighed in on Hubbard's behalf. "Long John is not a bad man," wrote the Journal sports editor in his Nov. 5 column. "He is a big, easy going guy, never troublesome. Any citizen might get into the same trouble if he did not curb his resentment of the 'shakedown' to which late hour pedestrians are subjected by police in troublesome neighborhoods."

At his trial, Hubbard said the cops had incited the violence by using racial slurs. On Dec. 5 he was found guilty of resisting arrest and given a three-month jail sentence that was stayed pending appeal. He was still out on $500 bond the following May when he was arrested again for punching a woman.

"I hit her on the button," admitted Hubbard, who said she deserved it for "lifting her hand" at him. "I'm touchy when somebody raises a hand at me."

He was fined $25 for disorderly conduct in the latter case (the woman he socked was fined $10).

In August of '54, Long John was retried on the resisting arrest charge and again found guilty. "If society doesn't protect those who protect it, it is neither grateful nor just," said Judge Herbert Steffes, who doubled Hubbard's original sentence from three to six months in the House of Correction.

I always figured Long John got his nickname because he was a tall, rangy boxer with a long left jab, but I have been set straight on that score by LeRoy Allen, three-time Golden Gloves champion in the 1950s who trained with Hubbard at the Urban League gym.

"He was really a character, and quite the comic in the gym," says LeRoy. "He would walk around in the locker room in the nude just to show off his 'long john!'"

I stand corrected. And, frankly, even more in awe.