Milwaukee’s original "Greek Freak" Theodore Anton stood only waist-high to the current one playing for the Bucks. But in a match-up in Anton’s arena, 6’11" Giannis Antetokounmpo would be in over his head.

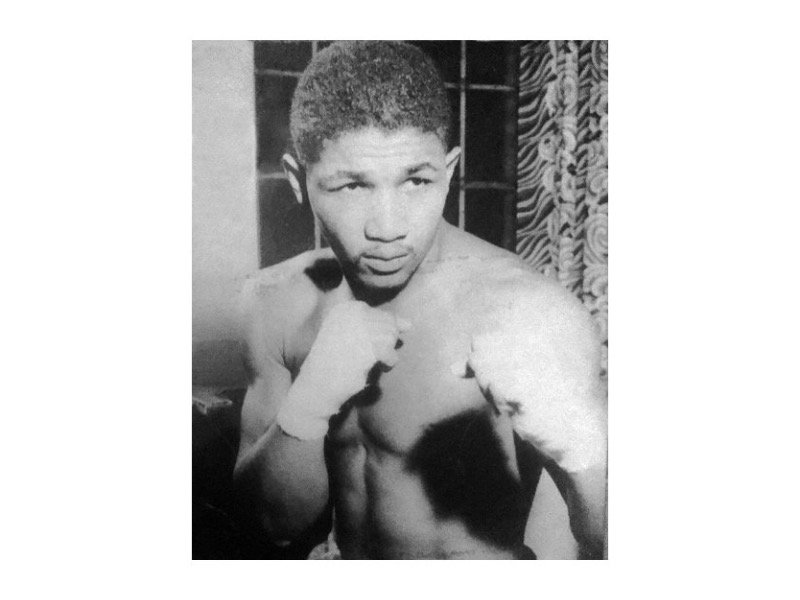

The only championship the boxer known as Anton the Greek ever claimed was the welterweight title of Wisconsin, but what he lacked in fighting know-how, he more than made up for with guts and a determination to keep pitching leather no matter how badly he was getting licked.

Born Theodore Antonopoulis in Ageonsosten, Greece, on Sept. 2, 1891, Anton came to Milwaukee in 1902. The 14-year-old Greek weighed less than 100-pounds when he started out on fight cards at local theaters.

"Anton the Greek took enough punishment at the hands of Young Pinkey to founder the ordinary pug, but the pride of Wells St. weathered the storm trying for a knockout to the last," reported the Milwaukee Free Press on April 11, 1912.

What really gilded the Greek’s reputation as an indomitable tough guy and permanently endeared him to boxing fans happened at the Armory in Fond du Lac on Jan. 27, 1913. Fighting in the eight-round semi-windup bout, Anton and Bert Stanley of Oshkosh put on a battle described by the Fond du Lac Reporter as "full of action from start to finish" and "the best seen in the Armory in several seasons."

Stanley won by a wide margin, and after the final bell, Anton shook his hand and said, "Mr. Stanley, you were too clever for me."

"And you," replied Stanley, "were too tough for me."

The main event that night was to feature Fond du Lac’s Dauber Jaeger against the same Young Pinkey who’d whipped Anton handily in Milwaukee a year earlier. But 10 minutes before fight time, Pinkey suffered what the Reporter story called "’coldfeetis’ following an attack of ‘yellowstreakus’ in its most malignant type," and refused to enter the ring.

As the crowd booed and hissed, Anton the Greek offered to take on Jaeger himself after a 15-minute rest, a cold shower and a rubdown.

He got them – and then got his second beating of the night, with Jaeger "landing 10 blows to the Greek’s one" in their six-rounder. But the headline in the next edition of the Reporter – "Greek Anton A Real Fighter" – went all over the country, and Anton was famous.

He still wasn’t much of a fighter, but over the next few years, the Greek was in demand throughout the Midwest. He lost as much as he won, but nobody ever asked for their money back after one of Anton’s fights.

When he lost a tight decision to Bud Logan, Anton demanded a rematch and told the Free Press he would "meet Logan for a peanut or he will wager his grocery store against almost nothing that he can win."

The reference was to the market on 6th and Wells Sts. that was the Greek’s headquarters between fights. Anton and his relatives started the store from scratch and, by dint of nose-to-the-grindstone work, built it into a thriving enterprise. It turned out that the little fighter whose head was almost impossible to miss in the ring had one hell of a head for business outside of it.

Between the store and the boxing purses he didn’t have to share with a manager because he refused to have one ("I make my own matches and keep every cent"), Anton made money hand-over-fist and salted away every penny.

In 1914, Anton made headlines again when he took on two opponents in a single night in Grand Rapids, Michigan. After he knocked out Farmer Smith, one of the latter’s pals in the crowd stood up and challenged the Greek to fight. Anton beat him, too.

In 1916, with World War I looming up, Anton became a U.S. citizen. "I sure am glad that I am now an American citizen," he told reporters. "I think a good boxer would make a good fighter for his country."

He enlisted in the Army, and "even the $30 per day he received from Uncle Sam was saved," according to The Milwaukee Journal.

After more than 100 fights, Anton quit boxing in 1922 and moved from Milwaukee to Cicero, a suburb of Chicago. He opened a fruit stand that became spectacularly fruitful, sold out and then plunged into real estate. He built the Hotel Anton, bought another hotel called The Hawthorne, and also ran a smoke shop and restaurant on the same block.

In the mid-1920s, Chicago Mayor William E. Dever set out to rid his city of the mob forces at war with one another. One of his main targets, Al "Scarface" Capone, later to become America’s biggest crime lord, set up shop in The Hawthorne. He and the proprietor became pals, and Anton’s hotel became Capone’s headquarters – and a target for the police and rival gangs. The former raided The Hawthorne and charged Anton with keeping a disorderly house, and the latter strafed the building with machine-gun fire.

In November of 1927, Anton the Greek returned to Milwaukee in a chauffeur-driven car to see old friends. He bragged about a net worth of almost 150 grand (just about $2 million in today’s dollars) and indicated he intended to come back for good as soon as he could unload his Cicero properties for what he figured they were worth.

In the meantime, Anton reportedly did something even gutsier than taking on two guys on the same night: He told Al Capone to take his underworld operation someplace else.

So it was hardly a surprise a few days later when proprietor Anton disappeared without a trace from The Hawthorne Hotel.

On Dec. 4, his bloodstained overcoat was discovered near Des Plaines, Ill., and a month later, Anton’s body was found in a shallow, lime-filled grave outside Chicago Heights.

"Two bullets had been fired into the head and an inflammable liquid poured over the body and set aflame," reported the Chicago Herald Examiner. A finger had been cut off, apparently to make it easier for his killers to remove the victim’s $1,000 diamond ring.

Newspapers at the time said Capone ordered the hit, and several Capone biographies say the same. But descendants of Anton still maintain that a rival gang took him out and that Al wept over his pal’s death. Nobody was ever charged with the crime.

This much is indisputable: In the ring and out, nobody was less disposed to "coldfeetis" and "yellowstreakus" than Milwaukee’s first Greek Freak.