The "Coming Home" series, brought to you by the Milwaukee Art Museum, explores the lives of Milwaukeeans who moved away but ultimately returned to make a difference. The series is in conjunction with three current exhibitions at the Museum that expose how travel provides different ways to see the world and the everyday. Learn more about the Museum’s season of travel at mam.org/travel

Over the last 15 years, Rob Baker has organized from the front lines in Ferguson, worked with Snoop Dogg on anti-violence campaigns, sat in the recording studio with Dr. Dre’s team, led pioneering urban turnout efforts as executive director of the League of Young Voters, covered (and partied with) some of the biggest names in hip hop for The Source magazine, launched countless social activism projects and received his PhD from UCLA.

But now he’s back in Milwaukee. Why? Because he believes in this city – its creative arts, its youth and its potential.

It’s important, or maybe just interesting, to understand Baker, who goes by "Biko," as a nod to the assassinated South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, as an amalgamation of incongruous gifts – academic, athlete, activist, artist; writer with a musician’s ear, tech-savvy historian, sports guy who can code, pragmatic idealist.

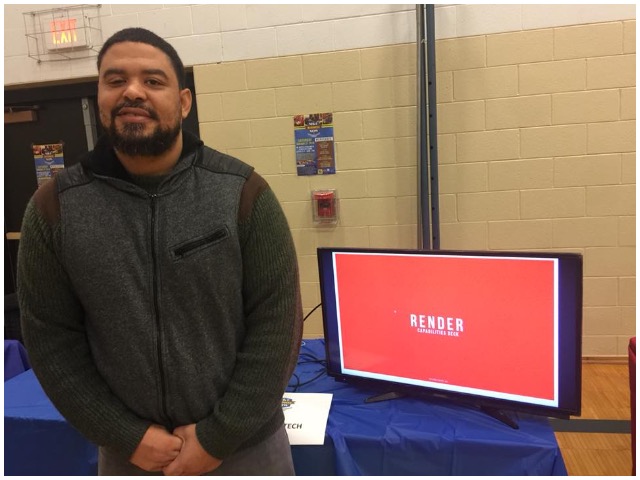

Even at 39, Baker talks in terms of jocks and nerds. As a still-playing soccer coach with a future-star son, he sees himself as a jock. But, as a history PhD sitting in his office at a technology consulting firm that develops solutions for social causes and public-sector clients, well, he’s kind of a nerd. You maybe wouldn’t say that to him – especially since he’s not wearing his glasses today – without first checking to see if there are any lockers to be stuffed into at Render, the digital storytelling company Baker founded in 2016 at 2209 N. Martin Luther King Drive. But he’d admit it; and he’d say he wants to groom the next generation of people like him, to do the types of things he does.

Growing up in the early 1980s near 77th Street and Silver Spring Drive, at the time one of the last – or, looking at it now, first – truly integrated parts of Milwaukee, Baker was a mixed-race kid who went to private Lutheran schools and excelled as a soccer player. And, for a long time, that was the lens through which he viewed himself and his world, as a "little precocious dude" who didn’t yet know he was smart.

It was at UW-Milwaukee in the late-1990s, when Baker gave up his soccer scholarship to focus on academics, that he determined to be if not a jock, then at least a cool nerd. He’d worked at the Boys & Girls Club with esteemed former U.S. men’s national team soccer player Jimmy Banks, coaching kids, reviewing budgets and basically learning how to run an organization at the age of 20 – "the biggest lesson for me," he says. He’d also acquired an unexpected affection for the library, and an itch to leave Milwaukee.

"At the time it wasn't cool to be a nerd," he says. "I remember reading hip hop magazines and thinking, I can do that, I'm going to go where the action is. I wanted to get where I could grow."

After graduating in 2000, Baker moved to Los Angeles to attend graduate school at UCLA, enchanted by the freedom and opportunity. While driving out to L.A., his cousin asked what he was gonna do out there, if he had a plan. "I don’t know," Baker replied. "I just want to be influential."

Since then, Baker has spent more than a decade both having plans and being influential, leveraging his tech skills, music connections, sports involvement, commitment to activism and aptitude for storytelling to impact communities – especially kids and young men – within and far beyond Milwaukee.

Out in Los Angeles, Baker immersed himself in the scene and hustled like crazy. He inhaled textbooks, explored the campus and city, worked for rap magazines while going to school and pretty much didn’t sleep. "I remember one time reading a review from my grad student," he says, "and it was like, ‘Rob is the best teacher, except sometimes I think he's asleep.’ It was an 8 a.m. class. I was probably just getting in the door two hours earlier."

With a PhD in the discipline, Baker can safely describe himself as a "history buff," though he doesn’t know exactly why he was drawn to it. "I liked the stories and felt like the past, you can reclaim something there," he says, before adding with a laugh, "I probably should have went and did computer science or political science."

While writing for The Source in the early 2000s, Baker and a friend linked up with rapper Xzibit, who had earned mainstream success hosting the MTV show "Pimp My Ride," to put on Rhyme Night, a huge hip hop talent show in the city. "I went from being just like a mixed dude from 77th Street to getting into L.A. parties," Baker says.

Soon, he was going to the studio with Bizzy Bone and Snoop Dogg, too, and working with Dr. Dre’s producer to get drops for a mix tape. Mostly, Baker was just "shutting up and watching," learning about sound, production and digital videography – stuff that came relatively intuitively for him, he says, because he was a 70s baby and "actually had to hook stuff up."

He was a sponge, but he offered some suggestions too. Baker remembers one time telling a manager that the rapper they were working with needed to shout out his name in the song. The manager said, "that’s vanity," to which Baker responded, "How is he marketing himself if he doesn't shout himself out? This is rap."

Almost everything else Baker did in L.A. revolved around writing and storytelling. During the day, he says, his "nerd job" was being the archivist for Reverend James Lawson, the Civil Right activist who in 1968 invited Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to speak during the Memphis Sanitation Strike, at which King was assassinated. Baker organized papers no one had seen in 40 years, and, along with the history books he was reading, started to feel inspired.

Meanwhile, he and his crew were on Hollywood Boulevard every night, working parties and doing events. He says it was a more invigorating vibe than in Milwaukee, where "the hood, it’s like a real environment." What he loved about L.A. was that being creative and entertainment-minded was cool, part of the culture; no people pulling you back, saying you can’t do it. "That grind and hunger," he says, "out there, it’s encouraged."

And, after a few years representing The Source as "a little dude from Milwaukee," while Shug Knight, the notoriously powerful music producer and executive, was still running Los Angeles, Baker felt a new level of respect, for himself and from others. "I knew I could come back here and deal with the drama," he says.

But in 2005, on a visit home, Baker absorbed a blow he wasn’t prepared for, and one that may have changed his career trajectory: He found out that four of the 12 kids he’d mentored in Milwaukee had been shot and killed, as well as others he knew from the old neighborhood.

He put grad school on hold to launch the Campaign Against Violence, which worked with local inner-city groups to talk, listen and demonstrate in some of the toughest areas of Milwaukee. Their goal was to increase kids’ self-esteem, give them reason to believe other people cared about them and – leveraging Baker’s street cred as a hip hop columnist – help them realize that the violence glorified in rap lyrics was fiction.

"Wanting to come back was seeing the city in a place where I knew that some of the skills I had learned organizing, some of the skills I learned in the music industry, knowing I had some amazingly talented friends and little homies, it was like, I can be a bridge between Milwaukee and L.A.," he says. "I couldn't be a bridge in L.A., so I had to come back."

Over the next two years, Baker split time between Los Angeles and Milwaukee, working to finish his degree while staying involved in the music business and getting more deeply engaged in social causes. "I came up at a time where hip hop and activism were almost synonymous," he says. "Whereas a lot of my friends did more the entertainment side in music, I stayed to the grassroots nature of it."

In 2008, after a few years as a volunteer, Baker became executive director of the League of Young Voters, a nonprofit advocacy organization that engages and mobilizes youth, especially those marginalized by the electoral process. The League focused on using hip hop and activism to get people involved – in politics, in their communities, to make voting cool. Nationally based in New York, Baker quickly made Milwaukee one of the main hubs.

Baker would spend eight years with the League of Young Voters, making national news appearances, producing digital activations like #BarackTalk, and #NoGunsAllowed with Snoop Dogg, leading get out the vote campaigns, building multi-racial and multi-issue alliances and impacting local, state and federal policy and elections.

"It was successful, man," Baker says. "We did a lot of data-driven stuff. I think people were impressed."

In 2014, he moved on to join ThoughtWorks, a global technology consultancy that was excited about the intersection of social media and social movements. "I spent two years inundated with nerds," Baker says." But ThoughtWorks gave him a fellowship to apply what he’d been doing to help advance causes that couldn’t afford a big software firm – to bring the price points down and be present for clients. One of those causes turned out to be a massive, life-changing one: Ferguson, Missouri.

On Aug. 24, 2014, a day before the funeral of Michael Brown, the 18-year-old African-American who was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Baker flew from Milwaukee to St. Louis Lambert International Airport – a flight he would repeat many, many times.

Over the next year, he stood on the front lines and chronicled behind the scenes, crafting an alternative narrative to the violent, extremist, literally burning and literally black-and-white mainstream media coverage of the protests and telling the subtler underground story that Baker believed to be vastly more important: Ferguson was ground zero for a new youth activism that was informed, engaged and organized, totally aware of the past and technologically capable for the future.

"I was involved deeply in Ferguson," he says heavily. "It became almost all-encompassing."

Between protesting, organizing, doing social media and writing about Ferguson for outlets like Vanity Fair, Baker helped set up the innovative Roy Clay Sr. Web Development and Entrepreneurship Workshop. It was a six-week intensive program that connected ThoughtWorks developers with selected St. Louis-area students to teach them tools like HTML, CSS, WordPress and some consulting skills, with the goal of boosting black-owned local businesses, as well as nonprofits and other social movements.

"So, you had kids who at night were protesting police, but then during the day they’re learning Java," Baker says. "It was the most tired I’ve ever been. But again, that shows you, like, ‘Yo, you’re a kid from Ferguson, and the world thinks that you’re probably some crazy person, but you’re in here trying to figure out how to do Java.’"

Baker speaks about his time in Ferguson with both obvious pride and clear weariness. But he saw the promise of the Roy Clay tech program, saw what it could be. He thought, what if this was something real? What if there was a shop in Milwaukee that introduced people to those valuable web tools, the opportunities to get ahead, and got them connected to the big firms? He wanted to come back and do that here.

"I was like, man, this is a lot of the stuff I was doing in hip hop," he says. "If you can produce a record, if you can think about the marketing of a record, if you can think about the release, if you think about the remix, that’s reiteration, that’s delivery cycle, that’s all these cool nerd terms.

"But I believe it can be applied because I was connecting things through sound cuz that’s what kids did in the 70s and 80s. But today, they’re fixing their grandma’s computer or installing Windows. The technology is different, but most people still just need a shot."

After two years developing scaled tech strategies for social movements, Baker in 2016 launched his own company. Render marries his passions and expertise, using digital storytelling, online activations and algorithmic social media to advance social causes and serve public-sector clients. Baker spent much of last year renovating his second-floor space, which now includes a main office, tech room, recording studio and an area where local community groups can come in and dance, play music and perform.

One of Render’s big projects right now is called MyBlackStory.us, an interactive site – launched in partnership with the Campaign for Black Male Achievement – that champions the positive efforts and impact of Milwaukee’s black leaders. It’s built on the intentional, interpersonal storytelling structure that emerged from the Obama campaign.

"That thing works, man," Baker says. "It's not an accident that Barack Obama was always getting all these big stump speeches that people were paying attention to, even people that didn't like him. People could see themselves in those stories, even with a guy named Barack Hussein Obama. With the proper structure, you can connect with almost anybody."

Render has a few associates and two to three interns that come in regularly, but right now Baker is doing most of the work.

"Startups are hard, man. To make a startup work, you have to give it all your time," Baker says. "You have to believe that the cash is going to come even if it's not there. For me, it’s getting a strong enough team of people who could help me in my blind spots. I am blessed."

When asked, Baker says his blind spots are money and budgets, which might suggest a challenge to a for-profit startup that already has to manage the tricky double bottom line of fiscal performance and social impact. But, as with everything else, Baker is approaching it the best way he knows how: creativity and hustle.

"When you're in that startup mindset, you've gotta go, you've gotta go, you've gotta go, whatever it takes, whatever it takes. Who do I gotta call, who do I gotta call, who do I gotta call? I'm really good at that," he says. "And then slowing down and saying we don't have to work as hard next month because we got our process steps together, I'm learning to be better at that

"Success to me is going to not be afraid to lose money."

While he’s been impressed with the city's restaurant and service industry expansion, as well as the increasing influence of the Milwaukee Bucks in the community, Baker says, "From where I'm sitting on Garfield Avenue and King Drive, it doesn't feel like there's a startup culture here."

Baker mentions an investor that he was connected to through – who else? – Snoop Dogg, but says, "I don't know a lot of super-wealthy people here taking a lot of risks, but they should.

"When you're dead and your money is going to your kids, that's great. But it could be re-invigorating a whole city."

Baker has experienced excitement and creative opportunity in Los Angeles, seen hate and violence in Ferguson, and knows too well the structural inequality and segregation here in Milwaukee. And yet, Baker still believes in Milwaukee. Why?

"There's a lot of talent running around here, man. There's like a lot, a lot, a lot of talent," Baker says, mentioning local rappers like WebsterX, as well as others he's helped get to Los Angeles. "In L.A., they used to call me Killer Milwaukee, cuz I was always grinding. If you can work and get a dollar out of nothing, that applies here too.

"I'm hoping the younger people coming up who maybe don't have the obstacles, because technology's less expensive, cost reduction is cheaper, I hope they continue with that same work ethic and stick to it. Because a lot of the dreams that people have can be had here."

Baker mentions that "Black Panther" was filmed mostly in Atlanta because it was cheaper, and posits that it would be even cheaper still to do business here. He wishes city leaders wouldn’t be so quick to talk about manufacturing and production jobs, that they would encourage something more aspirational. "The arts and technology is where it's at, man," Baker says. "It's so easy for a young person to become a millionaire quick if they figure out something online."

As for Milwaukee’s institutional racial issues, Baker the historian offers a reason for optimism.

"There's a lot of history to this city, and there's a lot of opportunity because there is this history," he says. "One of the things, when I was in Ferguson, I was struck by the fact that people from St. Louis had turned their backs on the young people there. I feel like it's a different story here. I feel like people … as ugly as it gets, we're still trying to figure it out.

"I think that's something that is unique. There's this DIY culture here, where people are going to push through it. I feel like if we do not get caught by old ideas – we did it because that's how they did it – we can get through it. Because a lot of the people I work with don't know the stories that hold us back. They don't know that they're not supposed to go across the viaduct; they don't know they're not supposed to hang on Brady. No one told them that."

When Baker starred for the Bavarian Soccer Club in the 90s, there were almost no other black kids playing the sport. "Now, I look around, everybody’s playing soccer," he says, a team photo of the Northwest-side Pride FC club he helped start, and fund, hanging behind him.

Speaking of soccer, Baker’s been playing more lately – not just kicking around with his son, but futsal, even jumping in at goalkeeper sometimes for the Majors league team he coaches – and estimates he’s about 50 pounds lighter than a few years ago, when he was sitting at a desk too much.

"Soccer is like my healing," he says. "I don't know anything else as powerful as sports at driving togetherness."

Still, as always, the jock.

Born in Milwaukee but a product of Shorewood High School (go ‘Hounds!) and Northwestern University (go ‘Cats!), Jimmy never knew the schoolboy bliss of cheering for a winning football, basketball or baseball team. So he ditched being a fan in order to cover sports professionally - occasionally objectively, always passionately. He's lived in Chicago, New York and Dallas, but now resides again in his beloved Brew City and is an ardent attacker of the notorious Milwaukee Inferiority Complex.

After interning at print publications like Birds and Blooms (official motto: "America's #1 backyard birding and gardening magazine!"), Sports Illustrated (unofficial motto: "Subscribe and save up to 90% off the cover price!") and The Dallas Morning News (a newspaper!), Jimmy worked for web outlets like CBSSports.com, where he was a Packers beat reporter, and FOX Sports Wisconsin, where he managed digital content. He's a proponent and frequent user of em dashes, parenthetical asides, descriptive appositives and, really, anything that makes his sentences longer and more needlessly complex.

Jimmy appreciates references to late '90s Brewers and Bucks players and is the curator of the unofficial John Jaha Hall of Fame. He also enjoys running, biking and soccer, but isn't too annoying about them. He writes about sports - both mainstream and unconventional - and non-sports, including history, music, food, art and even golf (just kidding!), and welcomes reader suggestions for off-the-beaten-path story ideas.