Various stories about the Packers' victory over the Bears last week called the NFC championship game perhaps "the biggest sporting event ever held in Chicago." In fact, it wasn't even the biggest sporting event held at Soldier Field.

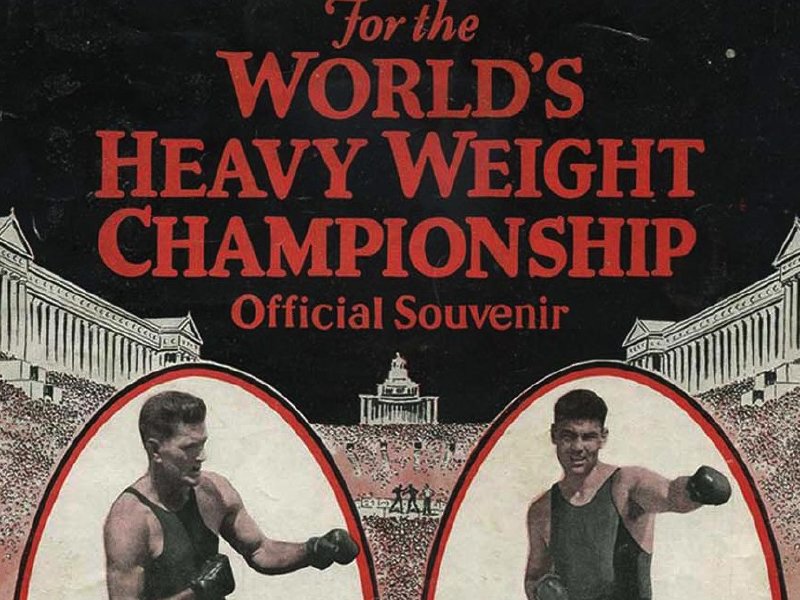

That distinction belongs to the September 22, 1927 heavyweight championship rematch between champion Gene Tunney and ex-champion Jack Dempsey, whom Tunney had unhorsed almost exactly one year earlier. The 104,943 persons squeezed into the stadium saw one of the most controversial boxing matches ever, known evermore as the "Battle of the Long Count" because Tunney may have been on the deck for more than 10 seconds after Dempsey tagged him in the seventh round but then refused to go to a neutral corner.

Looking out at the crowd, promoter Tex Rickard told a reporter, "...If the earth came up and the sky came down and wiped out my first 10 rows, it would be the end of everything. Because I've got in those 10 rows all the world's wealth, all the world's big men, all the world's brains and production talent. Just in them 10 rows, kid. And you and me never seed nothing like it."

Tunney won the 10-round decision and retained his title, but almost 84 years later it's the image of Dempsey's fierce scowl and the hammering fists that stove in Jess Willard's face in their 1919 title bout, and then crushed Georges Carpentier and Luis Firpo in boxing's first million-dollar gates that most vividly evoke the time when prize-fighting ruled sports.

None of that would have happened had Jack Dempsey's worst fears come true in Milwaukee 93 years ago this February 26. When the future "Manassa Mauler" stepped into the ring at the Elite Roller Rink on S. 10th and W. National that night, the guy in the other corner, Bill Brennan of New York, was considered a top contender for Willard's title. Among the many who figured Dempsey was in for a long, painful night was Dempsey.

"The only thought in my mind," he told Sam Levy of The Milwaukee Journal 11 years later, "was how much dough I was going to collect (for the fight). I was broke, you know, and I came in here an unknown. Brennan had a good reputation among the heavyweights of that day. The reason I started that fight with little thought of being a winner was because I had not forgotten what Brennan used to do to me in New York gymnasiums. I was big Bill's sparring partner for a long time and honestly, he used to knock the stuffings out of me."

It didn't help when Brennan dropped by Dempsey's dressing room at the Elite before the fight to remind him of those earlier times in New York.

"Jack, I'm sorry I have to knock you out tonight," he said, "but I'm in line for a fight with Willard. Come around later and I'll take care of you."

Instead it was Brennan who needed taking care of after the fight, as Dempsey knocked him down five times before the fight was stopped in the seventh round. The last knockdown spun Brennan around so hard he broke an ankle.

Dempsey had arrived in town so broke that he took advantage of the free lunch at Morgenroth's saloon on W. Water St. (now Plankinton Ave.). His hangout was a tavern called The Hermit on 3rd St. between Wells and Wisconsin. He couldn't afford a hotel, so he stayed with Red Burman, a local gambler.

He got $800 for the Brennan fight and a national reputation. But instead of celebrating, he later wrote in his autobiography, "I wanted to die and for some years after that I wished I had died."

World War I was in full swing in 1918. As the sole support of his parents and wife, Dempsey was legally exempt from military service. Not long before the Brennan fight he'd agreed to pose for a recruiting poster hefting a sledgehammer in a shipyard. They put him in overalls but forgot to change Dempsey out of his patent leather shoes. When the poster was distributed, people had eyes only for those gleaming kicks and wondered why the strapping young, expensively shod prizefighter wasn't in the trenches in Europe.

Dempsey's first inkling about the resentment that poster caused came when he started for Brennan's dressing room at the Elite Rink to checked on his defeated opponent.

"...From both sides of the aisle I heard the word that was the worst I was ever to know for years," he wrote. "'Slacker' a guy in the middle of a row yelled at me. When I turned that way, somebody on the other side said, 'Slacker, you were lucky to win.'"

Over the years the catcalls first heard here grew in number and volume, even after the war ended and Dempsey won the title, until he was formally charged in 1920 with fraudulently evading military service. A jury needed only 15 minutes to acquit Dempsey (who was decorated for his service in the US Coast Guard during World War II).

A frequent visitor to Milwaukee throughout the 1930s, '40s and '50s, Dempsey never held it against the city. "I always like to come back to Milwaukee," he told Sam Levy in 1950. "This town really gave me my start to the championship and big money."