It was a love affair of epic proportions. And then, in the blink of an eye, it was over.

In 1953, the Milwaukee Braves, fresh off their relocation from Boston at the behest of owner and construction magnate Lou Perini, drew a then-National League record 1,826,397. Just one year later, they shattered the 2 million fan attendance barrier, a mark they would also surpass in each of the next three seasons. The star-crossed romance between city and team was at its zenith in 1957 when 2,215,404 fans crammed into Milwaukee County Stadium and were rewarded with Wisconsin's only World Series Championship.

"I didn't realize it at the time," Hall of Famer Hank Aaron said. "But after we won the seventh game of the 1957 World Series, everything started to go downhill."

Aaron, in speaking to authors Bob Klapisch and Pete van Wieren for their book "The Braves, an Illustrated History of America's Team," could not have foreseen the greatest sports success story instantly become the most tragic seemingly overnight.

The question of "where did it all go wrong" has lingered amongst Milwaukee Braves fans for generations. How could a team go from the highest of highs to extinct in just 13 years?

Some assert that the beginning of the end wasn't actually in October of 1957, but rather three winters earlier, on an icy Wisconsin evening, not long after the Braves broke the thought-to-be-impossible 2 million fan barrier.

"If Fred Miller had not died in a plane crash on December 17, 1954, he would have put together an ownership group in Milwaukee to buy the club from Perini," noted Milwaukee Braves historian Bob Buege says. "Fred Miller was Milwaukee's last true civic hero, in my judgment."

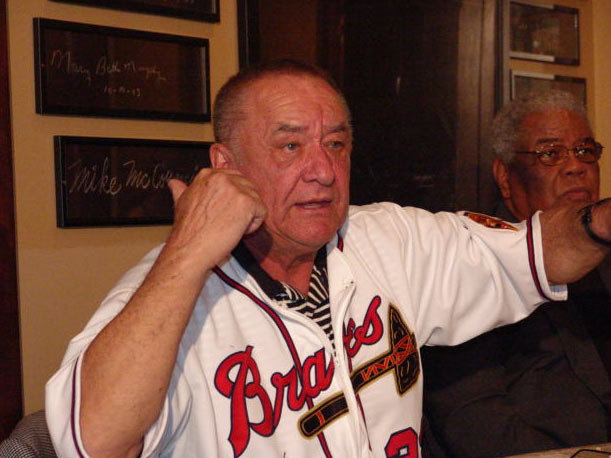

Ironically, the man who Buege says he despised, the man responsible for moving the Braves to Atlanta, Bill Bartholomay, agrees. "Frankly, if Fred Miller hadn't died in that tragic accident, he would have been the perfect guy (to keep the Braves in Milwaukee). (He was) one of the most wonderful people in Milwaukee at the time."

Frederick C. Miller was a giant of a man, both literally and figuratively. Captain of Notre Dame's 1928 football team, he returned to his native Milwaukee after college with the world at his fingertips. His father was a lumber, real estate, and mortgage mogul; his mother was heir to one of the most successful breweries in the country. In 1947, Fred Miller succeeded his uncle, Fredrick A. Miller, as President of the Miller Brewing Company. The younger Miller, a visionary, saw synergy between his product and sports. Through his efforts, both the Milwaukee Arena and Milwaukee County Stadium were built in the early 1950's. Miller then pushed hard for a Major League team to call County Stadium home, and helped convince Boston Braves owner Lou Perini that Milwaukee was perfect for his struggling ballclub.

For the rest of his short lifetime, Fred Miller was quite astute in his assessment of his hometown. Milwaukee was perfect. Some wondered if he was turning over in his grave a mere decade later, as his beloved Braves were pulling up stakes for the land of peaches and pecans.

The Milwaukee Braves never had a losing season. They appeared in two World Series, winning one of them. They had broken attendance records throughout the 1950's and averaged over 88 wins per season in the 13 years they were in Milwaukee. However, attendance was in a steady decline. Fans had become accustomed to winning not merely games, but championships.

"Attendance had been steadily declining in Milwaukee since the Braves' 1957 World Series victory," William Povletich, author of Milwaukee Braves, Heroes and Heartbreak says. "Fan apathy was further reflected in slow season ticket sales with many former Braves' fans caught up in the beginnings of Vince Lombardi's championship dynasty in Green Bay."

Further leading to a dwindling fan base was owner Lou Perini steadfast refusal to allow television of either home or even road games, despite other teams throughout the game reaping handsome advertising revenues by showcasing their teams in the emerging new media. Perini felt that if fans were allowed to see games for free, they would be less likely to come out to the ballpark where they had to pay to watch their heroes play.

One of the final tipping points that led to a full-on fan revolt in the spring of 1961 was the Milwaukee County Board banning carry-in in beer. Since Milwaukee County owned and operated the stadium, they felt they could make more money in concessions by forcing fans to purchase their favorite drink only within the confines of the ballpark.

Instead of buying beer at the game, fans simply stayed home, even after the ban was lifted the very next year. Attendance plummeted from 1.4 million in 1960, to 1.1 million in 1961, to just fewer than 767,000 in 1962. After turning an eye-popping profit of $7.5 million during the franchise's first nine years in Milwaukee, the Braves posted their first financial loss in 1962.

Perhaps sensing that the franchise would never again make money in Wisconsin; perhaps needing an infusion of cash to funnel into his struggling construction company, Perini decided to get out of the baseball business. Enter William Bartholomay, a 34-year old insurance broker that, with his Chicago-based investors, had purchased and then subsequently sold a minority stake in the White Sox in 1951.

Even though the Braves had lost money the previous year, Bartholomay knew what he was getting himself into. "The Braves were in a tough situation in Milwaukee because we couldn't really expand our broadcasting base much, or our fan base," Bartholomay says today. "Western Wisconsin had taken to the Twins, the Chicago teams, mostly the Cubs, were all over the place. I thought we could turn it around and draw about a million-and-a-half people, and that would be enough to sustain."

After a lightning-quick 10-day negotiating period, Lou Perini and the Bartholomay group agreed on a $6.2 million purchase price for the Braves. Part of the sale agreement centered on a $2 million balloon payment due in 1968. Looking to generate revenue quickly, Bartholomay offered equity shares of stock to Wisconsin residents prior to the start of the 1963 season.

The sale was a resounding dud. Of the 115,000 shares that were offered to the public, only 13,000 were purchased. Coupling the anemic stock sale with the fact that Bartholomay could not secure a $500,000 broadcasting deal; the new owners began to look for a new home.

In the early 1960's, Atlanta was beginning to take shape as the financial center of the Deep South. It was also a city that had no major league sports, and they wanted in on the game.

"Atlanta offered the team $2.5 million in broadcasting fees for a seven-state empire of baseball-deprived households between the Atlantic Ocean and Mississippi River," Povletich says. "From a purely financial standpoint, Bartholomay's interest in Atlanta could not be ignored."

Noted baseball economist and author Andrew Zimbalist agrees. "Atlanta was just a better market. It was also completely untapped. It was the south," he says. "There weren't teams in Texas, there weren't teams in Florida. There were no teams in San Diego; there were no teams in Phoenix. Based on opportunity, based on market, they were being entrepreneurial."

Bartholomay says if it wasn't the Braves that were going to be Atlanta's team; it was going to be someone else's. "In the 1960's, there were different pressures, sociological pressures, civil rights bills. All sorts of things were taking place. The 'new south' was opening up to some extent," Bartholomay says. "They were going to build a stadium and do everything they could to get a team. It wasn't just our ownership, but the entire National League that thought it was time to find a team that would fill out the map of the United States by having a team in the southeast. That never got very much attention, but that was a very important factor."

Milwaukeeans didn't see what those inside the game saw, however. Most Braves fans looked at the Atlanta threat as nothing more than a scare tactic to goad fans into buying more tickets.

"It never occurred to fans that the Braves might leave," Buege remembers. "When I read at the time of the 1963 All-Star game that the Braves might go to Atlanta, I simply did not take it seriously. No one did. The Braves had been so successful since arriving in 1953 that leaving was out of the question."

It wasn't to be. After an ugly battle full of rancor and legal maneuvers between the team and Milwaukee County, the Braves were allowed to leave for Atlanta beginning with the 1966 season.

In the years following the Braves departure to Atlanta, a new investors group led by Bud Selig led the fight to bring Major League Baseball back to Milwaukee. In April of 1970, Selig and his investors acquired and moved the bankrupt Seattle Pilots to Milwaukee and renamed them the Brewers. But that still leads to the question of "what if" to Braves loyalists that yearned for the days of Aaron, Spahn, Mathews, and Adcock.

"Of course, there were a lot of things that could have been done, probably much better," Bartholomay remembers. "The original ownership group that I put together, which was the same group that had the White Sox, initially could've actually included more Milwaukee people, and that probably would've been a good thing, and I could've reached out in that area."

Others say it might have even been simpler than that. "They could have been more involved in the community," Zimbalist says. "They could have squelched any rumors they were intending to leave, and also behaved in a way that would have been consistent in squelching those rumors."

But in the end, it was as the times dictated. Faced with economic and social realities of the 1960's, the time had come for a major league sports franchise to be headquartered in bustling and growing Atlanta. For a generation of Milwaukeeans, though, it marked the sad end to one of baseball's most romantic eras.

However, even the loyalist of the team's fans could not deny that the only course of action that was feasible was the path taken by the now-Atlanta Braves in 1965.

"They were deceitful and underhanded and disingenuous," Bob Buege says of the Bartholomay ownership group. "And if I had been in their situation, I'm sure I would have been just as despicable."

Doug Russell has been covering Milwaukee and Wisconsin sports for over 20 years on radio, television, magazines, and now at OnMilwaukee.com.

Over the course of his career, the Edward R. Murrow Award winner and Emmy nominee has covered the Packers in Super Bowls XXXI, XXXII and XLV, traveled to Pasadena with the Badgers for Rose Bowls, been to the Final Four with Marquette, and saw first-hand the entire Brewers playoff runs in 2008 and 2011. Doug has also covered The Masters, several PGA Championships, MLB All-Star Games, and Kentucky Derbys; the Davis Cup, the U.S. Open, and the Sugar Bowl, along with NCAA football and basketball conference championships, and for that matter just about anything else that involves a field (or court, or rink) of play.

Doug was a sports reporter and host at WTMJ-AM radio from 1996-2000, before taking his radio skills to national syndication at Sporting News Radio from 2000-2007. From 2007-2011, he hosted his own morning radio sports show back here in Milwaukee, before returning to the national scene at Yahoo! Sports Radio last July. Doug's written work has also been featured in The Sporting News, Milwaukee Magazine, Inside Wisconsin Sports, and Brewers GameDay.

Doug and his wife, Erika, split their time between their residences in Pewaukee and Houston, TX.