The building that houses the Charles Allis Art Museum, 1630 E. Royall Pl., on Milwaukee’s East Side was designed and built as a home, but in a sense it’s also always served as an art museum.

Built by a captain of industry, Charles Allis, the house -- designed by Alexander Eschweiler and built in 1909 -- was planned as more than a home for Allis and his wife, Sarah. It was meant to be a showplace for their ever-growing collection of art.

Allis was the son of Edward P. Allis, who arrived in Milwaukee from New York and purchased a tool and dye shop that he grew into the Allis Company.

"E.P. just kept adding onto the company and when he died in 1889, he was insured to the point where he was able to leave the company debt free to his wife and his kids," says John Sterr, interim executive director of the Charles Allis & Villa Terrace Art Museums.

At E.P.’s death, Charles was the company’s secretary-treasurer and by the turn of the new century, he was one of the city’s most prominent citizens and served as director of the First National Bank and the Milwaukee Trust Company, was a trustee of the Layton Art Gallery and Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company and was the first president of the Milwaukee Art Society.

In short, Charles Allis was a very, very rich man with a taste for fine art. And, as he and Sarah had no children, they were free to travel and spend their time at home and abroad seeking out and acquiring paintings, furniture and other objects.

By the time they moved into their new East Side mansion from their previous digs in Yankee Hill, the couple had been married 35 years.

"They wanted to do a Tudor style (home) as an ode to their English heritage," says Sterr, who notes that both husband and wife traced their roots to the Mayflower. "They hired the prominent German architect Alexander Eschweiler to execute that, which is kind of ironic. You will see the Tudor rose motif throughout the mansion."

Those roses are in the gorgeous plaster ceiling in the main hall and in the gorgeous, restrained stained glass windows that illuminate the grand staircase. Sterr says that the Allis’ had hired no less than Louis Comfort Tiffany to do this glass, but in the end used a design drawn by Charles himself.

The home was completed in 1911, Sterr says, noting that it was fireproof --poured concrete -- and fully electrified. All the fireplaces were -- and still are -- gas-powered.

"All the walls are about a foot thick and how do we know that? I've seen drill bits like two feet long trying to get through the walls," says Sterr. "Not only the threat of fire back then was still very real, but also they were building it to house the art collection, so important to have fire protection."

The home is stunning both inside and out. The exterior is faced in mauve-brown Ohio brick with Lake Superior sandstone trim and it’s got a great collection of steeply pitched gables that create an almost Escher-like view from the roof.

There’s carved sandstone balcony above the main entrance that is mimicked by a pair of similar carved details on a porch on the east side of the home. The railings were created by Cyril Colnik.

To the west is the former coach house, which had a rotating platform so Allis’ driver could pull straight in and then out again without ever having to shift into pesky reverse. Remnants of this can be see in the coach house basement, which still has its giant coal bin and the works for a house-wide vacuum system.

It’s nearly impossible to catalog the detail work inside. Nearly every surface is gorgeously carved or turned or adorned. The kitchen was kitted out with all modern conveniences. A small elevator was installed between the kitchen and the servants’ quarters above the coach house.

Intercoms connect every corner of the place.

And the same can be said for the art. In this room there’s a quirky Tiffany lamp.Upstairs the Allis had museum-style glass-fronted display cases built into the walls. One room is full of French Barbizon paintings. On the porch are two stone baptismal fonts that had to be shipped across the ocean. There’s a similarly hefty fountain in the dining room.

"It must have been gentlemanly bowling," quips Sterr, "because if you were to bowl like people do now down this alley, I think there would be more scuff marks on the walls."

I offered to allow Sterr to act as pinsetter while I rolled a frame, but he declined. Off the billiards room is a full body shower unusual for its time that Sterr describes wittily and pretty accurately as, "part Hannibal Lechter and part Kohler."

There are some secret panels to be found, including one that holds the Allis safe. Though there are no greenbacks in the safe, there is a collection of 78 rpm discs.

On the roof, there’s a deck with a low iron railing and nice views of the city and, incidentally, of a couple brick chimneys that Eschweiler was kind of enough to detail for lofty visitors.

They were not pinching pennies were they?

"They were not," says Sterr. "I feel like the footprint of this place is fairly modest. It's the details and the artwork that they spent the money on."

But Charles didn’t get to enjoy the splendor for long. He died seven years after moving in and Sarah lived alone -- though likely with a cook and chauffeur, and with visiting nieces and nephews -- until her death in 1945.

"In 1945, she honors the intention of Charles and herself to donate the home to the citizens of Milwaukee," says Sterr. "No one really knew how that was going to happen, right? Who’s going to take it over, should we take it over, why should we take it over?

"She was donating the home and the collection and a small endowment to a public entity, but then there's pages and pages of ‘if not that then this.’ She's planning for the fact that, ‘okay if the city doesn't want it’ ... the collection remains intact. It can only be shown. Nothing can be added or deleted -- these were kind of parameters. The library system is the one that stepped up."

Milwaukee Public Library took control of place and transformed it into the Allis Art Library, open to the public. It continued thusly until 1979 when it was transformed into Charles Allis Art Museum.

An addition was put on to the north in 1998, allowing the museum to host special events and to raise money by renting it out for weddings and other special events.

The art pretty much looks as it did when Sarah Allis died in 1945.

"We don't lend any out and we don't add anything to the collection, " says Sterr. "That's kind of really a jewel, too. Not only the artwork that you can get up that close to and see, but you get to see it how wealthy industrialists lived with it and appreciated it.

"Not everything is out. They have more stuff than they could show: minerals and gemstones, and other paintings and sculpture and what-not that are not on public view."

Last year, the museum was without heat during the winter but it won’t suffer again this winter, now that a new furnace has been installed.

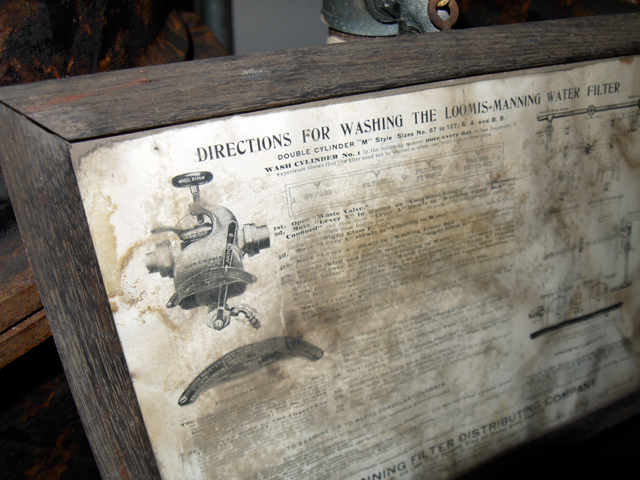

"Now we really have a state-of-the-art system," says Sterr, as we check out the new furnace, which sits next to the original one. A number of interesting old iron contraptions -- water cleaners, an incinerator, water heater, etc. -- survive in the Allis basement, making it also something of an industrial -- as well as an art -- museum.

Behind one of these walls there’s a wine cellar with cabinets that survive.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.