Wearing an American flag pin. Composing a well-worded tweet. Standing and applauding at a sporting event. There are no lack of ways to show one’s support for the troops in America.

While they’re undoubtedly appreciated, the tragic reality, however, is, with 22 veterans statistically committing suicide every day, our nation’s proven to be much better at the patriotic show than the actual support, great at protecting and defending the symbols – the uniforms, the flag, the anthem – and less so the very strong but still very human men and women returning from fighting under them. With the loud political commentary hurled from both sides, as well as what is often a gulf of uncertainty between vets and civilians, their essential voices, stories and struggles – the honest, unvarnished ones – are often lost in the clutter.

And that’s how a casualty of war is made right at home.

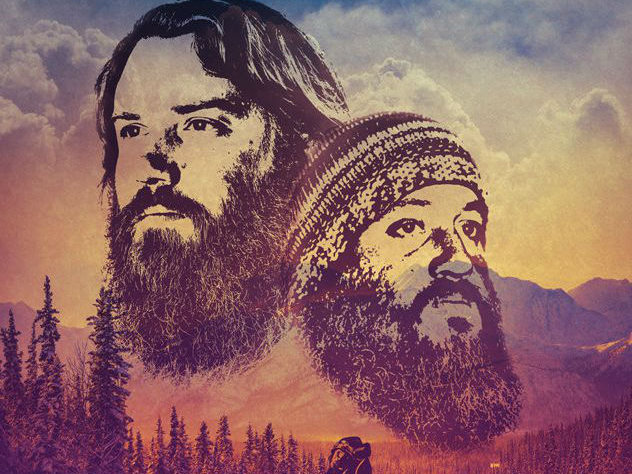

Amongst the stories of struggle – both on the frontlines and at home – that managed to break through the noise was that of Tom Voss and Anthony Anderson. In 2013, the two Milwaukee Iraq War vets packed up and took to the road for a trek across the country – both for their injured mental health and the health of others struggling like them. Three years later, their incredible journey still has legs thanks to "Almost Sunrise," Michael Collins’s honest, heartbreaking and, as the title implies, hopeful documentary chronicling a trek of healed blisters and healing psyches.

The "Wild"-esque Veterans Trek – originally Voss’s personal brainchild and then expanded into a larger awareness campaign when Anderson joined on – obviously serves as Collins’s key story hook, a journey of endurance and emotions with some of the most scenic, beautifully sprawling parts of America’s flyover country as a backdrop. Throughout the film, however, Collins and his editors often leave the road to bound back to Milwaukee, seeing how the families left behind are coping, as well as to talk to experts about the effects of PTSD and, most pressing for the film, the concept of moral injury, a feeling of guilt and shame haunting veterans back home.

Viewers hoping for an immersive, day-to-day chronicle of their emotional and physical walk might trot out mildly disappointed in the sometimes bouncy storytelling structure. To bring the focus on its macro-level issues, some of the micro-level minutia gets left in the dust. The difficulties of the road and the grind are mostly reserved to a quick early montage; Anderson, for instance, seems to struggle early on and slow things down, but the audience only gets a brief, vague clip of the situation. The complications of a sensitive emotional experiment blowing up into a nationally-covered story are also hinted at, but just left as hints.

While Collins occasionally sometimes with balancing his focus – a fellow Milwaukee vet’s tragic suicide, incorporated for a broader picture of the problem, is painfully heartbreaking and startlingly intimate, but unfortunately more tangential than tied in – when the small and large scale come together in stride in "Almost Sunrise," it creates an essential portrait of the veteran experience.

Anderson and Voss may be on their walk together, fighting similar issues – and sharing similarly unwieldy facial foliage – but the two provide two different perspectives. Anderson is the much more vocal part of the tandem, able to communicate his feelings – frustration, guilt, anger and then anger at that anger – at the VA process, the ignorance toward veterans’ issues at home, the experience of war, politics and, of course, with his own mental condition. Tom, on the other hand, is mostly quiet and secluded, many of the emotions clearly still tossing and turning in his brain.

Between their separate experiences – one achieves his breakthough along the road; the other’s quest continues well after setting foot at their final destination – and other brief interviews, "Almost Sunrise" captures a bracingly honest portrait of the issue. Anderson talks about his anger about the process of getting help and the uncertainly of the politics surrounding their war. Another vet, one from Voss’s squadron who actually took photos of the tour to remember and help process it, talks about assuming one’s death when fighting abroad – and how that shakes one up when returning home alive. And when Voss does occasionally open up, it’s heartbreaking and harrowing, talking about his guilt and, in one painful voiceover sequence, his unshakable memories, smartly flashed on screen almost subliminally by Collins over shots of the vet blankly walking on the trail.

Save for that and some beautiful shots of the American countryside and mountains, that’s about as flashy as Collins gets on his direction, but his simple, truthful approach helps shine light onto issues often left in the dark – even to those suffering from them. The movie doesn’t present the men as types with simple, inspirational or tragic arcs. Instead, they’re complex individuals, reflecting on and processing their feelings, with complex individual reactions to often horrific, morally vague moments. And Collins doesn’t present that problem as a simple one with easy blame or answers either. It’s one with many shades, such as the moral injury component – of not being sure one did right – that’s nicely explained and reflected upon throughout the film, or of the neat measuring of PTSD that’s anything but neat or helpful.

Of course, the untidiness of the issue leads the film away from a clean ending, as the final act follows one of the vets into a further, meditation-focused therapy. While Collins tries to keep the momentum going, silent thoughtfulness in beige rooms is a bit of a comedown from the literal forward progress of revelations discovered on the road. Just visually, conference halls make for a hard follow-up to the vast rocky Western landscape; even the subject’s major breakthrough has to take place on a title card.

Even so, these quibbles don’t take away too much from the power of the film’s final thoughtful points and hopeful realizations, captured and presented with care and consideration. After all, it only makes sense that an honest portrayal of recovery and post-war hurt would reach an honest, truthful end. War is flashy and loud, external and blunt; it forces one’s attention. Recovery is the opposite: a quiet and internal fight against unseen enemies – but, as caringly argued by "Almost Sunrise," a fight just as in need of support.

"Almost Sunrise" = *** out of ****

As much as it is a gigantic cliché to say that one has always had a passion for film, Matt Mueller has always had a passion for film. Whether it was bringing in the latest movie reviews for his first grade show-and-tell or writing film reviews for the St. Norbert College Times as a high school student, Matt is way too obsessed with movies for his own good.

When he's not writing about the latest blockbuster or talking much too glowingly about "Piranha 3D," Matt can probably be found watching literally any sport (minus cricket) or working at - get this - a local movie theater. Or watching a movie. Yeah, he's probably watching a movie.