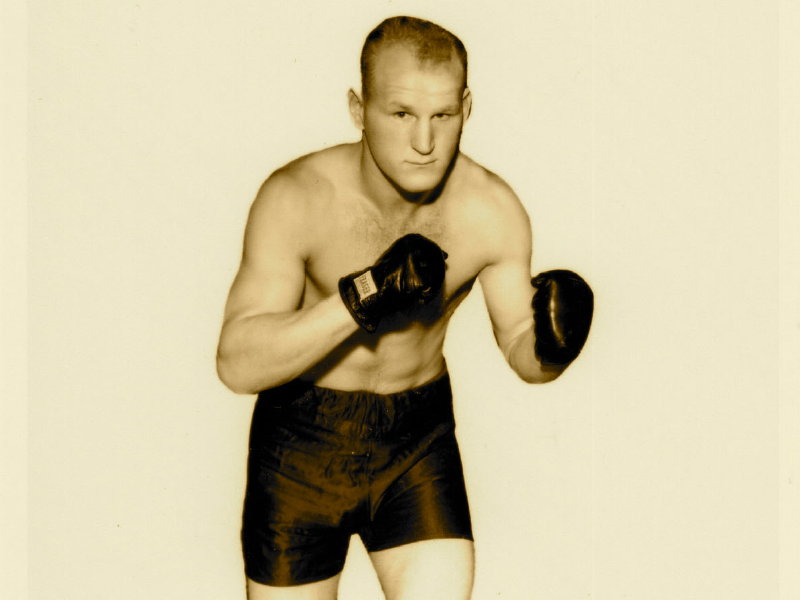

Not every tough guy from Green Bay wore a football uniform, and 75 years ago, Adolph Wiater proved it by almost throwing Joe Louis for the first loss of his legendary boxing career.

When they fought in Chicago on Sept. 26, 1934, the Brown Bomber left the ring a winner by the narrowest of decisions. Louis went on to win the heavyweight championship in 1937, hold it for 12 years (with 25 successful defenses), and is recognized by many boxing experts as one of the greatest boxing champions.

In his 1978 autobiography, Louis recalled that night at the Arcadia Gardens arena when "Wiater hurt me some and stood his ground. He was a crowder, the first man to bring blood to my face."

Louis biographer Richard Bak wrote that Wiater "proved as rugged as the weather back in his hometown. He crowded Joe all night."

If injuries to his arms hadn't hampered him and eventually ended his career, Ad Wiater might've crowded his hometown professional football team right out of the Wisconsin sports spotlight. (Imagine a world with no Packers vs. Favre hype.)

Boxing was a popular sport here when Wiater started out in the 1930 Golden Gloves tournament. The graduate of Green Bay East high school won a couple state titles and was picked for several international meets. When he turned pro in 1933, his first manager, Green Bay pickle maker Leslie Kelly, sent him by train to Chicago. That's where most of Wiater's fights were held. His first loss, by decision to Ernie Evans, was in Milwaukee. According to The Milwaukee Journal's Sam Levy, the verdict stunk. Wiater knocked Evans out in a rematch.

Wiater's first pro fight in Green Bay was a fifth round TKO over Peshtigo's Merrill "Red" Tonn in 1933. Over the next six months, Wiater won nine fights in a row, including a decision over Johnny Paycheck, who'd fight Louis for the title in 1940.

Johnny "Baker Boy" Risko had been an upper-tier contender for a decade when he came to Green Bay to fight Wiater on Aug. 18, 1934.

The fight at City Stadium, then home of the Packers, was the centerpiece of the state convention of the American Legion. Risko had beaten plenty of good fighters -- including current heavyweight champion Max Baer -- and was famous enough to be featured in two large front-page advertisements in the sports section of the Green Bay Press-Gazette the week of the fight. Sponsored by the local Stone Motor Company, in the ads Risko endorsed the "Chrysler Airflow" automobile.

Unlike some celebrity pitchmen, Risko's honesty was beyond rebuke. Not long before, he'd told legendary sports editor Arch Ward of the Chicago Tribune, "If there were any good fighters around I would quit. But they are all bums, including myself; but I am one of the least worst."

But endorsements didn't come much heartier than the one for Wiater in the Press-Gazette a few days before the fight -- especially when critics of boxing derided its practitioners as "plug-uglies."

"If you were to talk long with Ad Wiater," Harry Conley wrote, "and particularly if you dropped any remarks about his being near the top, he would squirm a little, search around for the right expression to use in telling you that the big hurdles were all made in getting the breaks and opportunities... We like to hear this boy, who is getting nearer and nearer to a crack at the World championship, say that right here in Green Bay there are many fighters who have greater ability, finer qualities, and are more capable. We certainly don't think so, but it gives us an inside light on Ad that does not show when he is in there, driving and hammering out a victory. However, it is the thing that makes us proud of Ad -- his love for his home, his hometown, and extremely modest answers to any praise.

"Why do we like the Green Bay Packers? Is it just because they win? The are Green Bay boys to us, and we like Ad Wiater for the same reason, because he's real, honest, a champion in the making, and on top of it all, just a modest, inspiring youth."

The Wiater-Risko bout was the first boxing match ever held outdoors in Green Bay, which was too bad for the local hero because it turned out to be the only one in Wisconsin ever TKO'd by the weather.

Wiater was ahead on points when severe thunderstorms that caused more than $40,000 in damage throughout Green Bay soaked the fighters and the 4,000 fans at City Stadium. The fight was stopped in the fifth round after lightning struck a transformer and the stadium was plunged into darkness.

It went into the record books as "No Contest," and afterwards Risko admitted that Wiater "hit me as hard as some of the best heavyweights in the business have done." Veteran referee Walter Houlehan told Art Bystrom of the Press-Gazette that "he never saw a youngster look as good against a veteran as Wiater did."

Wiater's growing reputation put him "in kind of a tough spot," wrote Bystrom 10 days after the Risko fight. "The best boys won't take him, for fear of ruining a reputation at the hands of a comparative unknown, and the second-raters don't want him for they know they haven't a chance."

Right below that pronouncement in the Press-Gazette was a boxing result from Chicago the night before: "Joe Lewis, 187 ¾, Detroit, knocked out Buck Everett, 183, Gary, Ind., (2)."

The misspelling of his surname notwithstanding, Joe Louis had a growing reputation of his own. A national amateur champion in '34, he had reeled off six impressive wins as a professional. When Louis -- "a sharpshooter ... who waits for an opponent to lead and then unleashes crashing wallops to the head or body" and Wiater -- "an aggressive, methodical fighter who has demonstrated ability to absorb hard punches without weakening" -- were matched, the Press-Gazette said it "may go a long way toward determining which will come closest to his goal -- a world's title bout."

In the first round a Louis wallop caught Wiater on the jaw, and he went down. But he leaped up before the referee could even start counting, and any notion that Louis was in for another easy night were dispelled over the next few rounds as the Green Bay fighter kept on top of Louis and outfought him.

Forty-one years later, Wiater recalled in an interview with Press-Gazette sportswriter Jim Egle that Louis "was going to quit by the eighth round because he'd taken too much of a beating. Somehow his manager stuck a pin up his seat to make him fight."

The Associated Press report of the fight said it "was close all the way with neither having a wide margin," but the final two rounds "Louis won with a fast flurry of punches to gain the decision."

A talked-about rematch didn't happen, and in his four remaining bouts that year Wiater went .500. By then, bone chips and calcium deposits in his elbows, aggravated by his style of mixing it up inside, were an increasing problem. He had surgery in 1935, with the result that he never again was able to fully extend his arms.

"After the operation I lost everything," Wiater recalled in the 1985 interview. He retired from boxing in 1936 with a record of 19-6-3, with 10 KOs. After that, Wiater moved to Chicago for good, spent 41 years working in a print shop, and was grateful for the things he didn't get in boxing -- "I've got my brains. I didn't get them knocked out. Thank God I didn't get them knocked out" -- and what he did get from it:

"Because of being in the ring, I'm a better man," he told the Press-Gazette. "I am more understanding, more tolerant."

He died in 2000 at age 88, and today Cheeseheads who can rattle off the names of everyone who ever played on the Packers' taxi squad probably never heard of him.

The man for whom their green-and-gold mecca at 1265 Lombardi Ave. is named would set them straight. On Wiater's application for a Wisconsin boxing license, one of his character references was the head coach of the Green Bay Packers, Curly Lambeau.