Nowadays the groundhog and its accursed shadow get all the attention at this time of year, but back in the 1920s, '30s and '40s people knew it was February when Harry Wills became a shadow of his old self by not eating any food for the entire month.

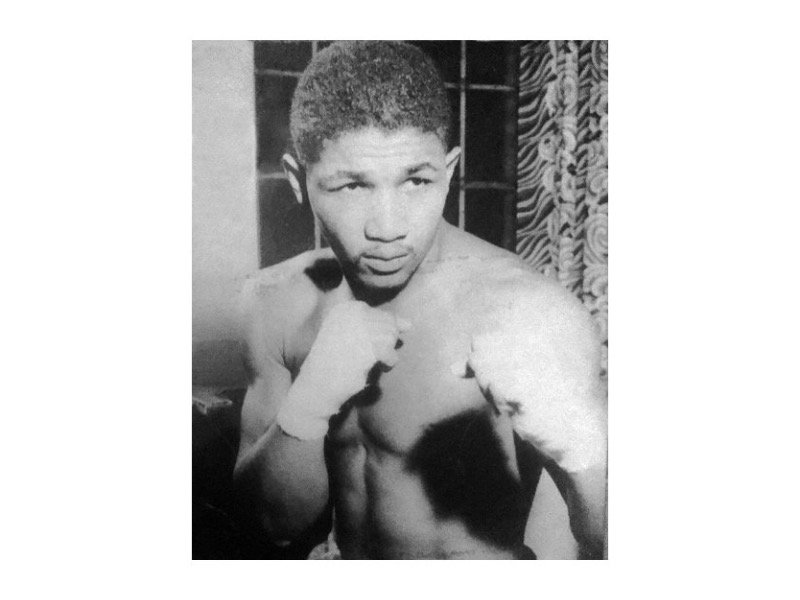

Nicknamed the "Black Panther," Wills was a great boxer who according to many experts might well have become the heavyweight champion of the world if he'd gotten Jack Dempsey into the ring when Dempsey held the title in the "Roaring '20s."

But it never happened because the people in charge of boxing then weren't about to put what was considered the greatest title in sports within reach of a black fighter after what boxing and white society had gone through with Jack Johnson. Johnson became the first black heavyweight champion of the world in 1908 and proceeded to mow through a series of white challengers with discombobulating ease. His victory over ex-champion Jim Jeffries, the original "Great White Hope," in 1910 touched off race riots around the country.

Harry Wills started boxing professionally a year later. The 6-foot, 2-inch, 220-pound native of New Orleans was the top heavyweight contender for about a decade, but fearful politicians - reportedly including then-New York Governor Al Smith - made sure Wills never went for the big enchilada.

He was, however, recognized as the "Colored Heavyweight Champion" and in 1992 Wills was elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Though Wills never fought in Milwaukee, locals followed him closely. When he beat Luis Angel Firpo on Sept. 11, 1924 before 75,000 fans in Jersey City, New Jersey, a crowd estimated at up to 6,000 clogged North 4th Street in front of the Milwaukee Journal building to hear reports from ringside telegraphed to the paper and then announced to the crowd through a megaphone.

After retiring from boxing in 1932, Wills invested his ring earnings in real estate in Harlem and lived comfortably – except in February, when he embarked on his famous annual month-long fasts, putting nothing in his mouth but water for, as one story put in 1934, "the good of his health and his immortal soul."

Wills started his annual fasts in 1911 when he supposedly accompanied an acquaintance afflicted with gout to the famous Battle Creek Sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan. His friend got well after a prescribed fast, and Wills adopted the practice of giving up food completely for a month. It was usually February because it's the shortest one, though Wills fasted once in March and once in April when business concerns precluded it in February.

Wills swore by the results.

"I am always hearty because I drive all the impurities out of my system by fasting," he said at the conclusion of his 1934 food embargo. "I lay off eating and take long walks and cold showers, and I never have any business with the doctors. You never will catch me in a doctor's office."

It wasn't easy, Wills conceded.

On the third day of his 1934 fast he was asked "Don't you get hungry at all?"

"To tell you the truth, I sure do," Wills replied. "Tomorrow is the crisis day. After tomorrow I'll get along all right."

It didn't help during World War II when the whole country was on a diet thanks to government-ordered food rationing.

"It was bad enough to go 31 days without pork chops," the 51-year-old ex-fighter sighed at the end of his thirty-second annual fast in 1943. "Without havin' people talkin' forever about where they're going to get pork chops."

Wills wasn't the only famous faster that year. In India, Mahatma Gandhi went on a hunger strike around the same time. Gandhi lasted 21 days.

"Of course, he's 73 years old," Wills magnanimously allowed. "And he didn't have much of a body to start with. That safety pin was mighty close to his backbone when he started."

At the end of a month without food, Wills was typically 60 pounds lighter. He'd break his fast by drinking orange or grape juice at four-hour intervals, and then switch to milk for several days before eating a couple soft-boiled eggs.

The total starvation regimen kept Wills in the headlines for decades after his boxing career was done. Such headlines read: "Harlem Grocers Are Gloomy as Harry Wills Prepares For Fast" in 1934, "Harry Wills Goes On Annual Fast; It's Guaranteed To Cure Anything" in 1942 and "Black Panther Begins Annual 30 Day Fast" in 1943.

But it was no publicity stunt.

"If everybody would fast like this once a year," Wills said. "There wouldn't be much business left for doctors."

Wills went into the hospital with acute appendicitis in late 1958 and died there on December 21 at age 68. Diabetes was given as the cause of death. He regretted to the end that he never got to fight Dempsey ("I'm sure I could have beaten him"), but not - so far as I'm aware - that he went three or fours years of his adult life, cumulatively, without eating.

Stuff your idiotic groundhog. February is Harry Wills Month to me. I wish I had the willpower to observe it by shutting my pie-hole for the duration, leastways because if there were six more weeks of winter ahead I'd be too miserable to care.