There was a West Allis man named Willard Eimermann whose existence I was wholly unaware of until I read his obituary in the local newspaper three years ago. It has stuck with me since because, according to the article, when Eimermann was born in 1916 his father named him after Jess Willard, who was then the heavyweight boxing champion of the world.

Today, nobody names his kid after the heavyweight champion; except for rabid boxing fans, hardly anybody even knows who the heavyweight champion is. (Small wonder, since there are at least five claiming that distinction, and most of them are from overseas.)

But 95 years ago, nurseries all over the country were probably full of little Willards named after the Great White Hope who ended the reign of the hated Jack Johnson on April 5, 1915.

When Johnson became heavyweight champion in 1908, it was a hot poker up the wazoo of white America, which so fervently resented that what was then the grandest title in sports belonged to a black man -- and one who unapologetically preferred white women, to boot -- that a frantic dragnet began for a properly-hued fighter to unhorse him.

The seven-year parade of White Hopes featured hulking farm boys, ranch hands and factory workers who eagerly fed themselves into the boxing grinder to escape the drudgery, anonymity and poverty of their daily lives. For most, the rewards were paltry and the punishment harsh; but even the least of them were heroes when they marched off to redeem white pride by challenging the fighter derided even in the pages of The Milwaukee Journal as "the dinge" and "the big smoke."

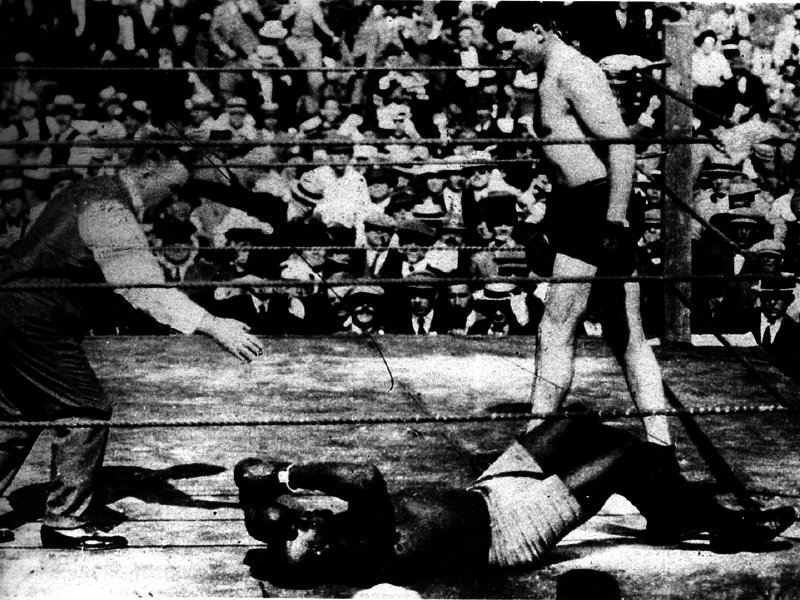

A 6-foot, 6-inch, 230-pound Kansan, Jess Willard knocked Johnson out in 26 rounds, and The Journal reported that "Milwaukee went fight mad when the news was flashed that the championship had been brought back to the white race. ‘Let's hope (Willard) is wise enough not to fight a colored man again' was heard on all sides."

According to a subsequent article, the "chocolate dropper" himself had the same notion. "I'm glad I fought the winning fight for the supremacy of the white race," declared the new champ. "And I stand ready to meet all the White Hopes that want to challenge me. But no BLACK HOPES need apply."

It was a startling comeback for Willard, who less than two years earlier had fought so abysmally in a Milwaukee bout that The Journal's story about it was headlined, "If Willard Is A White Hope We Are Sorry For the Race."

The match was held at the Elite Roller Rink on South 10th Street and West National Avenue. In the other corner on Nov. 17, 1913 was another White Hope called Boer Rodel, who, despite being a foot shorter and 50 pounds lighter than Willard, was adjudged the easy winner by most of the newspapermen at ringside.

"What (Willard) does not know about the game of fisticuffs would take longer to tell than to dig another Panama Canal," wrote The Journal reporter.

As forgettable as the fight itself was, the back-story about it is legendary in boxing lore and the annals of sports con jobs.

Rodel's manager was James J. Johnston, called "The Boy Bandit" on account of the successful and sometimes ethically questionable finagling he did on behalf of his fighters.

George Rodel wasn't much of a fighter, but by claiming he was a hero of the Boer War in South Africa that occurred when Rodel was still in diapers, Johnston got Rodel lots of press.

Willard was in the news plenty himself, thanks to what happened to the guy he fought three months before he met Rodel in Milwaukee. John "Bull" Young died after Willard knocked him out in 11 rounds. Willard was charged with manslaughter, but the case was dropped and the unnerved big man reluctantly resumed his ring career.

Getting his first look at the giant before their fight, Rodel begged Johnston to call it off. Johnston snorted and said he had a plan to keep Willard from even coming close to hitting him.

When the fighters entered the ring at the Elite, Johnston sidled over to Willard in his corner. "You'd better be very careful with your punches tonight," he said. "Rodel's been having dizzy spells and the doctor told me only today he has a dangerous heart condition. He must not be jolted."

"What's he doing here if he's got a bad heart?" stammered Willard.

"It's too late to do anything about it now," Johnston replied. "Only I thought I ought to let you into the secret. You know, you're just getting over the killing of Bull Young, and one more killing might send you straight to the electric chair!"

Wisconsin didn't have capital punishment, but Johnston wasn't giving Willard a civics lesson. For 10 rounds, the petrified Willard didn't so much as glare at Rodel.

Word about Johnston's sting got out, of course, and before he made the world safe for guys named Willard by deposing Jack Johnson 85 years ago this month, Big Jess knocked out Rodel twice.