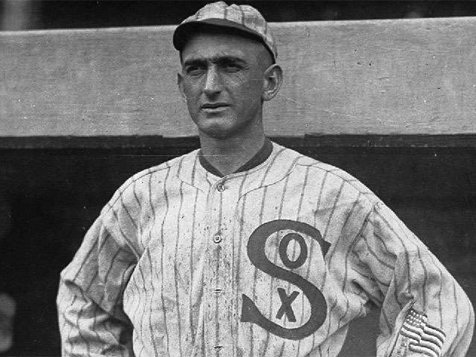

Twelve Milwaukeeans spent 18 days sitting in judgment of baseball legend "Shoeless" Joe Jackson in January of 1924.

It was just three years removed from Jackson's ouster from baseball for his alleged association with the 1919 Black Sox scandal resulting from the Chicago White Sox losing the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds.

Though it was actually Jackson's lawsuit for backpay against White Sox owner Charles Comisky, the jury was asked to decide whether Jackson did "unlawfully conspire with Gandil, Williams, and the other members of the White Sox Club, or any of them, to lose or ‘throw' any of the baseball games at the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Baseball Club?"

Shoeless Joe said it wasn't so, and 11 of 12 Milwaukeeans on the jury believed him.

OnMilwaukee.com spoke by phone with baseball researcher Gene Carney, whose book, "Burying the Black Sox" highlights the Milwaukee trial resulting from Jackson's lawsuit against Comiskey (note: Carney died unexpectedly last year after this interview) .

The White Sox had released Jackson when he was indicted along with seven other players for the scandal in 1920. Jackson was suing for the $16,000 owed him for the two years remaining on his contract. The trial took place in Milwaukee because the White Sox were incorporated in Wisconsin, which Carney speculated was linked to the fact that Comiskey had a summer home in the state.

However the 11 to 1 verdict in Jackson's favor was thrown out by Judge John Gregory on the grounds that Jackson had lied on the stand. "No one can commit perjury in the Milwaukee courts and get away with it," Gregory told the Milwaukee Journal.

Jackson was jubilant over the verdict despite it being overruled, and adamant that he had been honest. "That doesn't seem as though the jury thought I was lying," said Jackson. "Maybe in some things I was mistaken, but I didn't do no lying -- not that I know of."

The Milwaukee trial shows that Jackson was convincing in his claim that he played the 1919 series to win, and that he was not a part of any conspiracy, Carney told OnMilwaukee.com.

Supporters of Jackson have noted that the White Sox star had a great series against the Reds. Jackson made no errors in the field and hit .375 for the eight game series, with 12 hits, which at the time was a World Series record (the eight games were due to the fact that 1919 was one of the few World Series in which the format was best-of-nine rather than best-of-seven.)

Carney said the Milwaukee trial also undermines the portrayal of Jackson's 1920 testimony before a Cook County grand jury as a "confession."

Jackson detractors often use quotes from his 1920 grand jury appearance about intentionally striking out and just poking at the ball while batting. Carney said these statements are suspect because they only appear in press accounts, not in the actual transcripts of the trial. However the transcripts from the 1920 testimony do contain very clear denials by Jackson that he conspired to throw games.

Carney points to the testimony in Milwaukee of Henry Brigham, who had been the foreman of the Cook County grand jury. Brigham testified that Jackson had denied being part of a conspiracy in 1920. "If that's the way that the grand jury heard him [Jackson], that's really important," said Carney.

On the other hand, Carney said the jury in the Milwaukee trial did not parse through every detail of the 1919 World Series, and that much of the focus was on whether there had been a breach of contract. It was standard for baseball teams at that time to include what was referred to as a 10-day clause, which gave a team the right to terminate a contract without showing cause. Jackson, who was illiterate, claimed the White Sox deceived him into thinking the10-day clause had been waived for the contract he was signing.

And the trial in Milwaukee did nothing to lessen the damage of Jackson's admission that he had been promised $20,000, and accepted $5,000.

"That's still the big stumbling block for many people," said Carney. "It's seems incredible that he could be promised money, take money, but not do anything to earn money."

The perjury charge that ruined the case in the Milwaukee trial for Jackson was aided by a tactic of Comiskey's legal team, according to Carney. While preparing for the trial, Jackson's attorney Ray Cannon had been told that the transcript of Jackson's statement to the 1920 grand jury had disappeared. But one of the White Sox's attorneys suddenly produced the missing transcript while he interrogated Jackson, and read some of Jackson's 1920 testimony into the court record.

Carney said the problem for Jackson was that 1920 testimony was confusing and at times contradictory all by itself. "There's nothing he could have said in 1924 that could have agreed with everything in that statement, so he was kind of doomed."

While Carney said he's not sure what Judge Gregory based the perjury charge on, he suspects it was due to the inconsistency in Jackson descriptions of when he received the $5,000 from pitcher Lefty Williams. In 1920 Jackson told the grand jury he got the money during the World Series, but in the Milwaukee trial Jackson said it was after the Series.

Carney said he is one of the few baseball writers to use information from Jackson's back pay case against Comiskey. For example Eliot Asinof, the author of the best known book on the Black Sox scandal, "Eight Man Out," did not see any material from the Milwaukee trial, and only briefly referred to the it in his book. The 1988 movie based on the book did not refer to the trial at all said Carney.

Carney said the transcripts, depositions and exhibits from the trial are in the possession of a Milwaukee man named Thomas Cannon, who is the grandson of Jackson's attorney Ray Cannon. Cannon granted Carney access to the documents for his book.