With a name as suited to a Prohibition-era gangster as to a diminutive, sharp-dressed musician with a winning smile, the late jazz organist "Baby Face" Willette feels almost mythical. And the fact that he spent time in Milwaukee, not only pursuing a career, but building a life, albeit briefly, feels a bit like fiction.

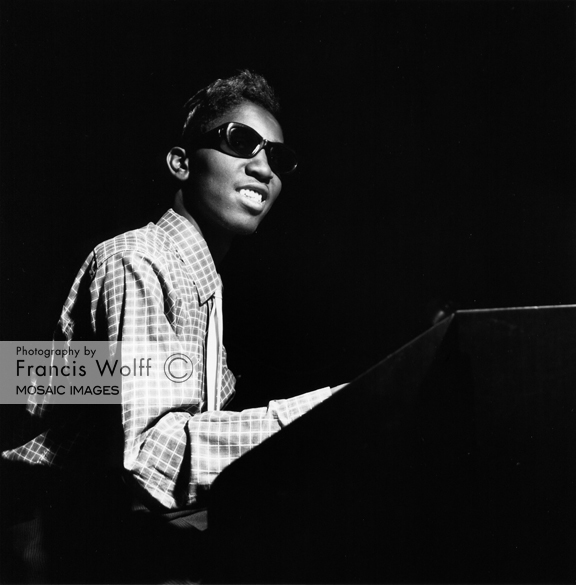

Who can imagine the dapper musician who wears a boyish grin on the cover of his second Blue Note LP, "Stop and Listen," and the sanctified ecstatic look on the sleeve of his 1964 "Mo’ Rock" disc, strolling along Walnut Street in Bronzeville, or hanging out at the Brass Rail on 3rd Street, between Wisconsin and Wells, or taking in a film at the Warner Theater?

But ghosts don’t leave footprints and though the traces aren’t many, Willette did leave evidence of his time in Brew City and some of it is quite enduring.

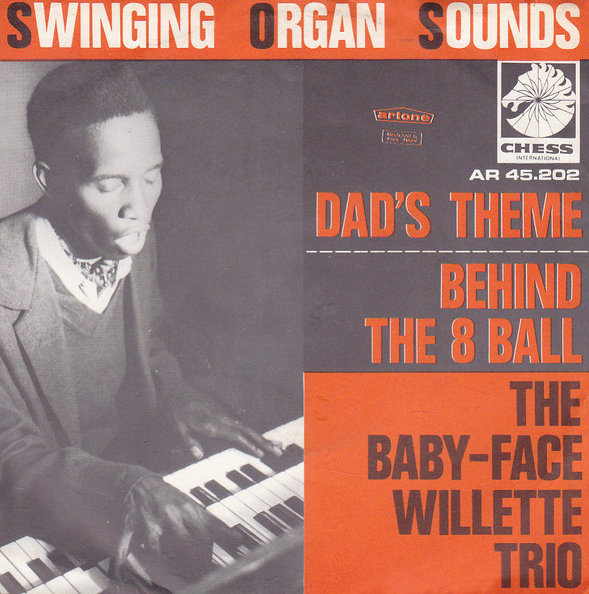

Willette’s recorded legacy is similarly sparse, but long-lasting. He left but two really fine soul jazz organ LPs for that giant-among-jazz labels, Blue Note, and a couple more for Argo, an imprint of the equally-legendary, Chicago-based Chess Records. Toss in a few 78s and 45s and a couple more sessions as a sideman with Blue Note and that’s it. Quality, certainly, but not much quantity.

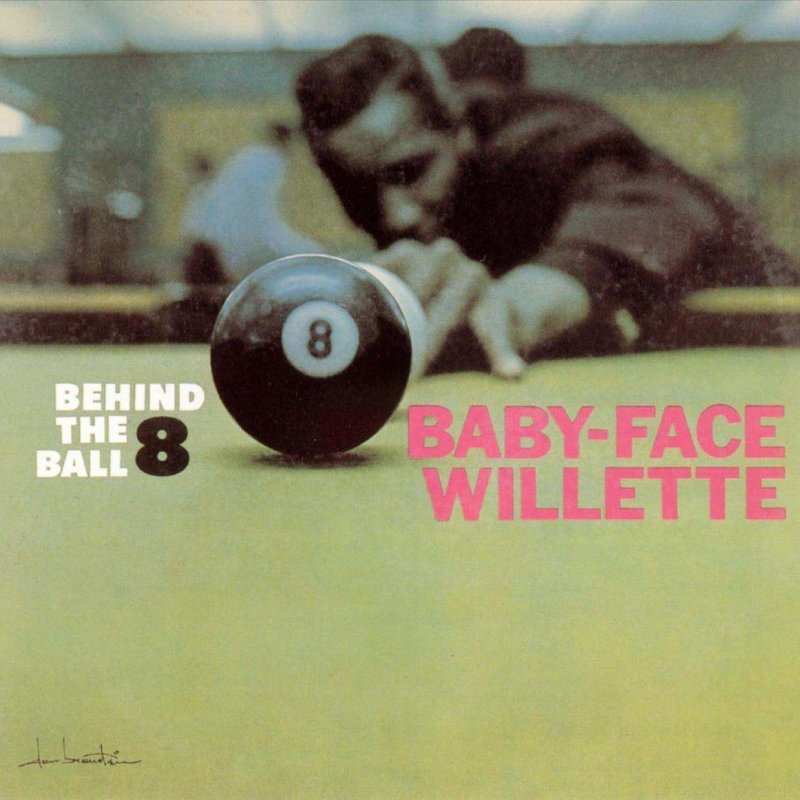

Alas, as the title of one of his Argo album covers depicts, Willette found himself behind the 8 ball, and not only was his career but a flash in the pan, his life was painfully short, too.

Who was Baby Face Willette, erstwhile Milwaukee jazzman? I was determined to find out.

Early life

Roosevelt Willette (aka Willet and Willett) was born on Sept. 11 in Little Rock, Arkansas, though the year (and birthplace; some claim New Orleans) depends on your source. His death certificate says 1934, but his grave marker claims 1936.

Roosevelt was the sixth of the seven children of Mansfield and Ardelia Willette whom were living just a tad over a half-mile from the Arkansas governor’s mansion at 1116 W. 21st St. in Little Rock when the boy was 5 years old. Though the house appears to be gone, the narrow lot and the small home next door suggest the nine Willettes didn’t have much room to spread out.

We don’t know why the boy was named Roosevelt, though it’s interesting to note that, perhaps coincidentally, Roosevelt Road was just a few blocks from the family home.

Roosevelt’s father, Mansfield, had been born into a large family of farm laborers in Woodville, Mississippi, on April 25, 1904, but had moved to West Feliciana, Louisiana (north of Baton Rouge) sometime before the 1910 census, in which his family was described as "mulatto." Mansfield made it as far as 7th grade.

In 1925 at age 21, Mansfield and Ardelia (nee Freeman), age 18, were married in Arkansas (though when they arrived there from the deeper south we can’t say) and by 1930 the two lived in a small house at 507 S. Valentine St., along with Mansfield’s younger brother, Ed, who worked in a cafe, and their children Daniel, age 3, and Georgia, who wasn’t yet 2.

In these days, Mansfield was working as a machinist’s helper, but by 1940, at age 35, he worked as a professional minister at the Church of God in Christ, 724 S. Gaines St., in Little Rock. In the previous year he said he’d earned $120 in salary but also a bit more from other unidentified sources. It’s possible that he earned some money through his work as a radio evangelist in Little Rock. Later in life, he would serve on the city’s traffic board, likely an unpaid position.

At the same time, it appears 33-year-old Ardelia was home with 13-year-old Daniel, 11-year-old Georgia Lee, 10-year-old Dorothy May, 8-year-old Eloise, 7-year-old Frank, 5-year-old Roosevelt and 1-year-old Robert Charles.

According to jazz organ historian Pete Fallico, Ardelia "was involved in missionary work connected with the church. She played the piano and no doubt started young Roosevelt on this instrument (some say at age 4)."

By 1945, the Willette family was living a little further west in the Stephens Area Faith section of Little Rock, and around this time Roosevelt was introduced to the organ and began studying music with his uncle Fred Freeman — Ardelia’s brother, three years older — who is said to have worked as a professional pianist in Little Rock some 20 years earlier.

"He started playing in church at a young age," Willette’s widow, Jo Gibson, would later tell Fallico. "His parents didn’t know he could play."

Gibson recalled when a pianist didn’t show up for service, Roosevelt asked his father if he could play and his father said no. "His mother said ‘let him do it so he’ll leave us alone,’" said Gibson, "and they were surprised to hear he could play."

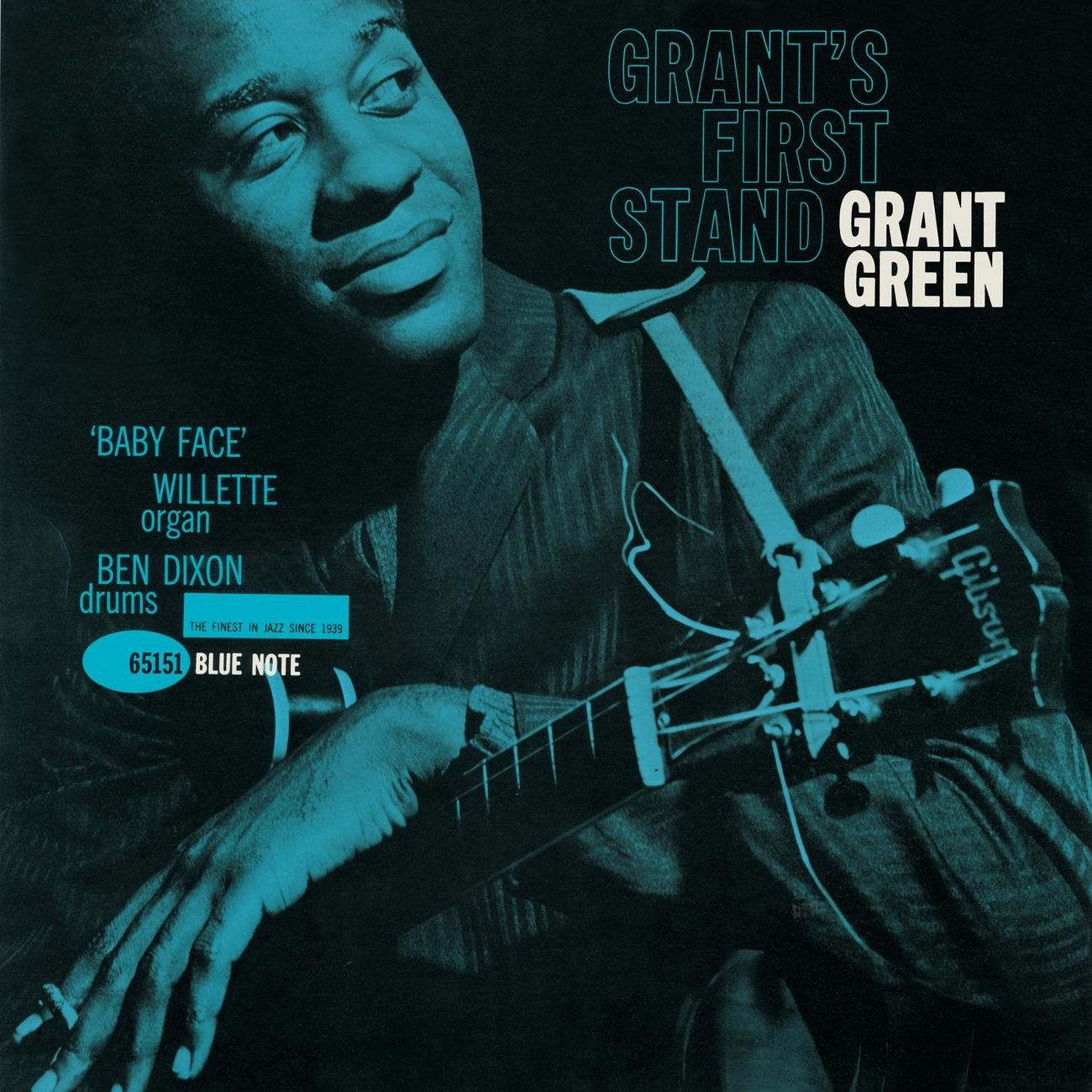

In the liner notes to Grant Green’s "Grant’s First Stand," on which Willette performed, Robert Levin suggested that Baby Face was introduced to the church organ at the age of 10.

A career is born

Later, though surely when he was still young, Roosevelt worked accompanying gospel groups put together by his sisters Dorothy and Georgia, who not only performed, sometimes on the road, but also recorded as the Willett Sisters, releasing "One Day" and "If I Were Hungry I Wouldn’t Tell You" in 1948 for New York’s Apollo Records.

A year earlier, Apollo issued Dorothy’s "Strange Things Happening Every Day" and "I Claim Jesus" on a 78, too.

In 1954, the sisters released another disc — this one on the Timely label — with "Lay Down My Heavy Load" backed with "Don’t Take Everybody to Be Your Friend."

It’s unclear whether or not their little brother performed on these recordings, though Roosevelt, age 20, was embarking on a career of his own, albeit in the world of rhythm and blues, touring the country — as well as Canada and Cuba — with the likes of Johnny Otis, Guitar Slim, Big Jay McNeely, Joe Houston, King Kolax, Joe Liggins and Roy Brown.

At some point, Willette also performed with The Caravans, a long-lived gospel group whose roster of members over the years includes the likes of Shirley Caesar and disco star Loleatta Holloway among others.

Levin wrote, "He was almost perpetually on the road, scuffling from town to town. From New Orleans and Little Rock he went west, with stops in Texas and New Mexico, to Los Angeles, where he worked with Johnny Otis and Big Jay McNeely. From L.A. he went to St. Louis, then on to Detroit, Cleveland and up into Canada, as far east as Montreal, working with various groups and for periods that lasted anywhere from several nights to several months. He covered New England for a time, then journeyed west once more, through Pittsburgh, Toledo, Chicago (where he established what was to become a home base), Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Denver and Salt Lake City. Returning to Chicago intermittently he then spent a good deal of time in the south and southwest: Oklahoma City, Dallas, Memphis, Atlanta, Birmingham, Miami, Havana for three months, etc."

"(Touring) was always a hassle, " Willette was quoted as saying in the liner notes to his "Face to Face" disc, which say that Baby Face spent nearly 15 years on the road. "I would just go where there was work."

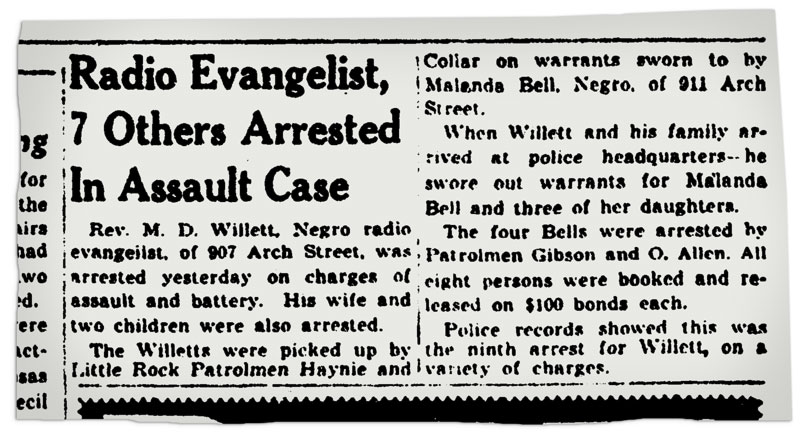

While it’s nigh impossible to reconstruct a detailed timeline of where Willette was during these years, we can say with certainty that in May and June of 1950 he was in Little Rock with his family, living at 907 Arch St.

This we know thanks to news items that recounted a May 31 altercation that led almost the entire family into the courtroom of Judge Harper Harb on June 16.

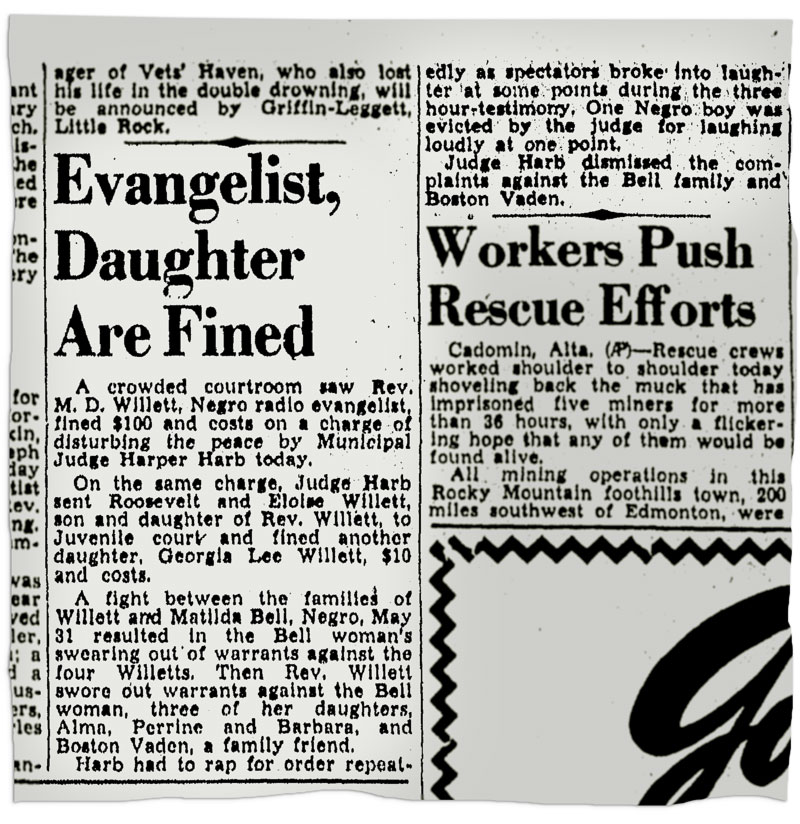

"A fight betwen the families of [Rev. Mansfield] Willett and Matilda Bell, Negro, May 31 resulted in the Bell woman’s swearing out of warrants against the four Willetts," reported the Arkansas Democrat. "Then Rev. Willett swore out warrants against the Bell woman, three of her daughters, Alma, Perrine and Barbara, and Boston Vaden, a family friend."

Everyone was arrested, booked and released, each on a $100 bond, though Ardelia was not arrested because she’d been at work when the fracas broke out. The Arkansas Gazette noted that, "This was the ninth arrest for [Rev.] Willett, on a variety of charges"

Without ever explaining the cause of the fight, the Gazette said that Mansfield was fined $100 and his daughter Georgia Lee $10, while Roosevelt, then age 16, and his sister Eloise were referred to juvenile court. The complaints against the Bells and their friend were dismissed.

"[Judge] Harb had to rap for order repeatedly," noted the Democrat, "as spectators broke into laughter at some points during the three-hour testimony. One Negro boy was evicted by the judge for laughing loudly at one point."

By 1952, out in California, and already nicknamed "Baby Face" for his youthful visage, Willette made what appears to be his recording debut as a leader with the release of "Wake Up, Get Out" on the Recorded in Hollywood label. It’s possible Willette was introduced to the label while touring with Liggins and Houston, who both recorded sides for the imprint.

"Wake Up, Get Out" was a rollicking R&B number with Willette on piano and vocal, and the record was backed with "Cool Blues."

Chicago and Milwaukee

Soon afterward, it seems, Baby Face established his base in Chicago, where his sisters Georgia Lee, Dorothy Mae and Eloise, brother Daniel, and grandmother Mollie Kennedy also lived. Interestingly, in 1957 his mother Ardelia also lived there, apparently separated from Mansfield, who remained in Little Rock.

After landing in the Windy City, according to Fallico, Willette "traveled through the Midwest several times but found himself returning to Chicago with some frequency. Here … is where he watched local gospel organists Maceo Woods and Herman Stevens. In them, he heard a thrilling style of playing that he could easily relate with."

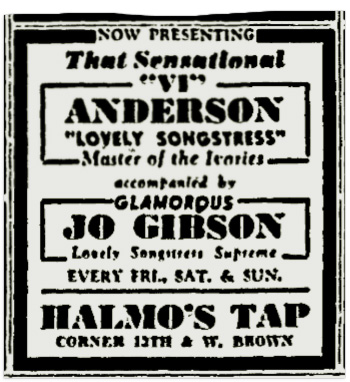

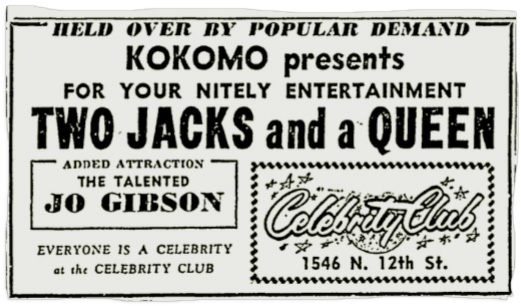

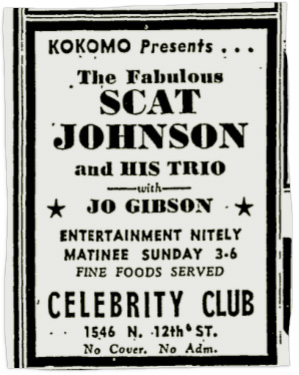

It is also around this time that Willette arrived in Milwaukee and met Jo Gibson, who was working the Milwaukee jazz scene as a singer at night and as an office secretary at the Veterans Administration by day. Newspaper advertisements show her performing at Halmo’s Tap on 13th and Brown streets as early as 1952 and at the Celebrity Club, with Scat Johnson and his trio, at 12th and Galena in ‘54.

Many of the clubs that Willette and Gibson performed in are long gone and these two are no exceptions.

Gibson later recalled that she and Willette met in Milwaukee, while she was working at one club and he at another.

"He had come here from Chicago, where he’d been working at the Squeeze Club," she told Fallico. "He had people standing (in line) outside (his gigs) in Milwaukee."

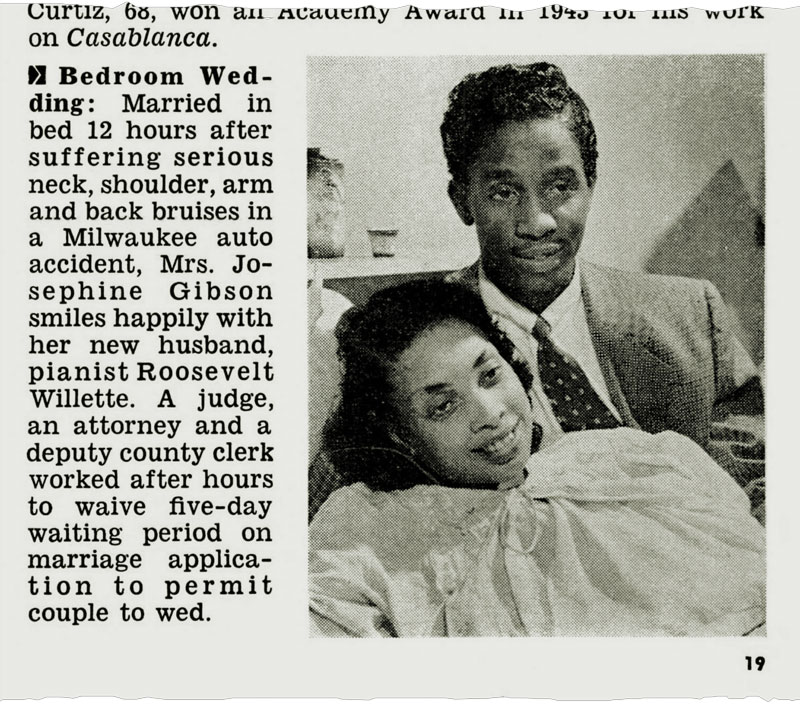

The two were married in Milwaukee on Sept. 28, 1955 and the union made the newspapers, due to some rather unusual circumstances.

"A Milwaukee woman was married Wednesday night even though she was flat on her back from an automobile accident earlier in the day. Mrs. Josephine Gibson, 27, of 1725 W. McKinley Ave., and Roosevelt Willette, 25 (sic), of 1920 W. Cherry St., were wed at Mrs. Gibson’s home late at night. This was just 12 hours after she suffered serious bruises to her neck, shoulders, arms and back in a collision at N. 17th St. and W. Juneau Ave."

The crash prevented the two from appearing before Judge Thaddeus Pruss at the County Courthouse that afternoon. Instead, Willette arrived and explained the circumstances to the judge. Because of the accident, Gibson had been unable to sign the license application.

The Journal continued:

"Before all the necessary steps could be arranged the courthouse’s 5 p.m. closing hour had passed. Willette then got in touch with Atty. Sydney M. Eisenberg, whom he knew, who came out of a religious service. He called Judge Pruss at home and Gerard Paradowski, deputy county clerk, at the Stadium, where he was watching the Global World Series."

Paradowski got the necessary documents together and the three went to 17th and McKinley, where Gibson and Willette were married.

"They and friends of the couple crowded into Mrs. Gibson’s bedroom for the ceremony, which was performed about 10:30 p.m. Mrs. Gibson lay in bed during the ceremony. Willette sat at her side."

The story was so captivating that it even went national the following month, when Jet magazine picked it up and ran a blurb with a photo of the newlyweds together on the bed.

The Vee-Jay sides

During his recent tenure in the Windy City, Willette — still playing piano, not yet organ — had connected with a young Vee-Jay Records. Baby Face would surely have known the label on which the influential Chicago gospel organist Maceo Woods released his debut in 1954.

Though Gibson told the Journal that, "plans for a honeymoon to Illinois had to be delayed," it appears the day after his newsworthy nuptials, Willette went immediately to Chicago to record four sides for the label, with Red Holloway on tenor sax, pianist Jon Thomas, guitarist Lefty "Guitar" Bates, bassist Rhodell Fox and drummer Moses Weedseed.

Red Holloway

Holloway was born in Arkansas, like Willette, but had landed in Chicago by the 1950s, where he performed with jazz musicians like Yusef Lateef and Dexter Gordon, bluesmen like Roosevelt Sykes and Willie Dixon and R&B singers like Lloyd Price. His musical path also crossed with those of Billie Holiday, Ben Webster, Lester Young, Aretha Franklin, Bobby "Blue" Bland and Chuck Berry.

The versatile Holloway worked as a session musician on numerous sessions for not only Vee-Jay, but also the United, Parrot and States labels.

Lefty Bates

Guitarist Lefty Bates was an Alabama boy who moved first to St. Louis and then, as a teenager, to Chicago, where he became a fixture on the city’s booming blues scene, working with John Lee Hooker, Buddy Guy and Jimmy Reed, as well as R&B performers like the Flamingos and the Impressions. In addition to leading his own combo, he, like Holloway, did much session work during the 1950s.

Jon Thomas

Pianist Jon Thomas — born in Mississippi in 1918 — is most likely the R&B musician who worked as a session musician for King Records and made his name later, playing organ on a series of Mercury releases like 1958’s "Big Beat on the Organ," and working with the Chicago-based quintet led by bassist Johnny Pate.

Two of the tunes — "Why" and "Can’t Keep From Lovin You" — would see release on a 45 in February 1956, while "The Thrill of Love" and "My Baby’s Gone" remain in the can even today.

The released sides are both vocals. "Why" is an uptempo number with piano and sax atop a rhythm section of bass, drums and guitar. Meanwhile, the flip side is a slow blues tune that kicks off with an organ intro — performed most likely either by Willette or Thomas — before that instrument fades back into the ensemble.

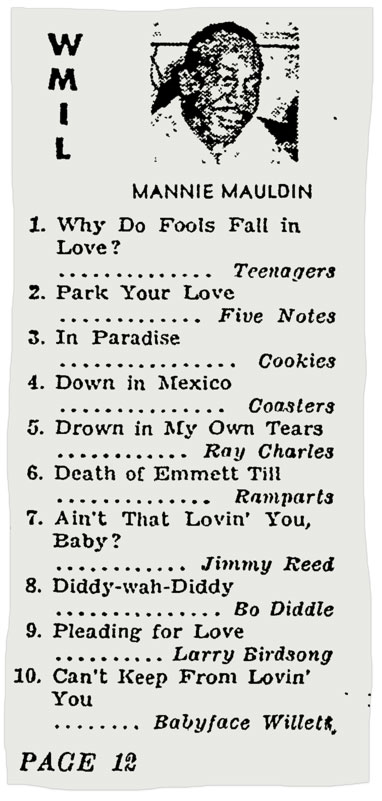

This record drew at least some attention in Milwaukee, it seems. The Sentinel newspaper on the morning of March 18, 1956 included six charts of the top 10 records from "Top D-Js" in Milwaukee and WMIL’s Mannie Mauldin – a radio personality whose extremely long presence on the Brew City airwaves endured at least into the late 1980s – included "Can’t Keep From Lovin’ You" on his list.

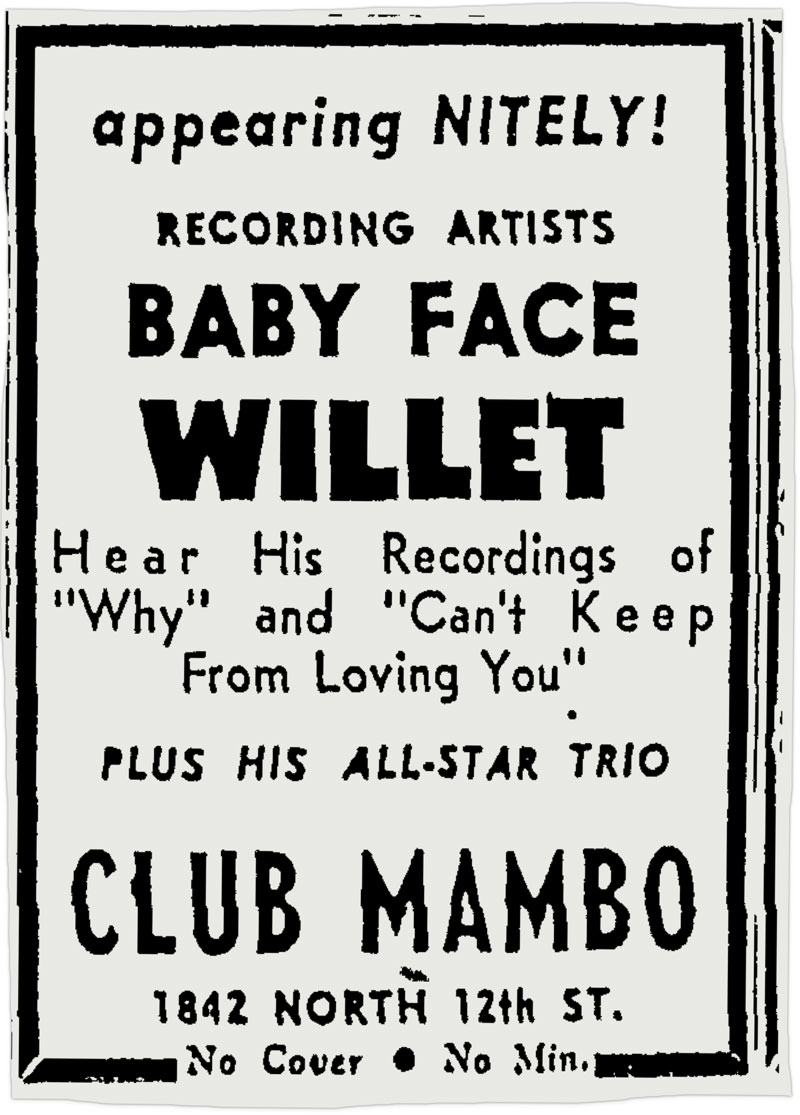

A few weeks earlier, the same paper carried an ad for "Recording Artist Baby Face Willet," performing nightly at Club Mambo on North 12th Street. "Hear his recordings of ‘Why’ and ‘Can’t Keep From Loving You’ plus his all-star trio," the ad boasted.

On March 29, Willette was back in Chicago performing at a show at the Trianon Ballroom at 62nd and Cottage Grove with The Dells, Eddie King’s band and, atop the bill, Chuck Berry, illustrating that Baby Face was still a crossover artist, with feet in both the jazz and R&B worlds.

At this point, Willette was doing hairdressing gigs out of their apartment while also performing in Milwaukee clubs, sometimes together with Gibson and her group.

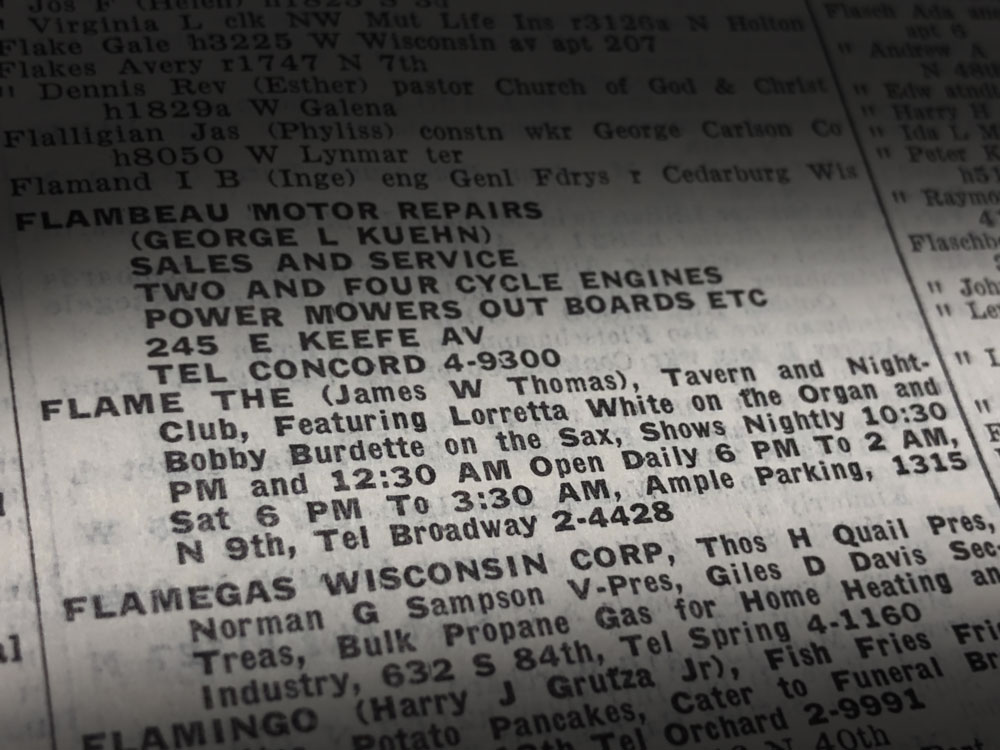

They had worked together — her singing, him playing — at the Moon Glow (which was opened by 1939 at 1222 N. 7th St.) and Max’s Tap on 3rd and Walnut Streets, at James "Derby" Thomas’ Flame Club, and a stint at Louis Atinski’s Pelican Club, 1241 N. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr.

The Flame (as with The Pelican) must’ve been a lively enough hot spot, considering how often it made the papers for being burgled, the scene of shots fired, the outbreak of fights, or for having its acts arrested for suggestive performances and its license suspended for infractions like serving minors.

By the time Gibson and Willette were performing at The Flame, owner Thomas had also taken over the Moon Glow, which had cycled through a number of operators since opening. It, too, had its share of drama and scrapes with the law until it closed in 1955, again under new management.

But The Flame still hadn’t yet dimmed and by early 1958, the club was hosting two shows nightly. Often onstage was Milwaukee organist — and Thomas’ wife — Loretta Whyte, with the similarly legendary saxophonist Bobby Burdette.

At this point, Willette was still making incursions back and forth across the often fuzzy border between jazz and R&B. "We were able to work together on tunes that were famous at that time," Gibson told Pete Fallico, adding that tunes by Ray Charles were part of the repertoire.

Gibson recalled in her interview with Fallico that Willette had a trio that included California blues and R&B singer Riff (Edward Nehemiah) Ruffin and that often Willette played 3 p.m. matinees on Sundays, which is supported by mention of a matinee in a Pelican Club ad from 1957, with Danny Reed on tenor sax.

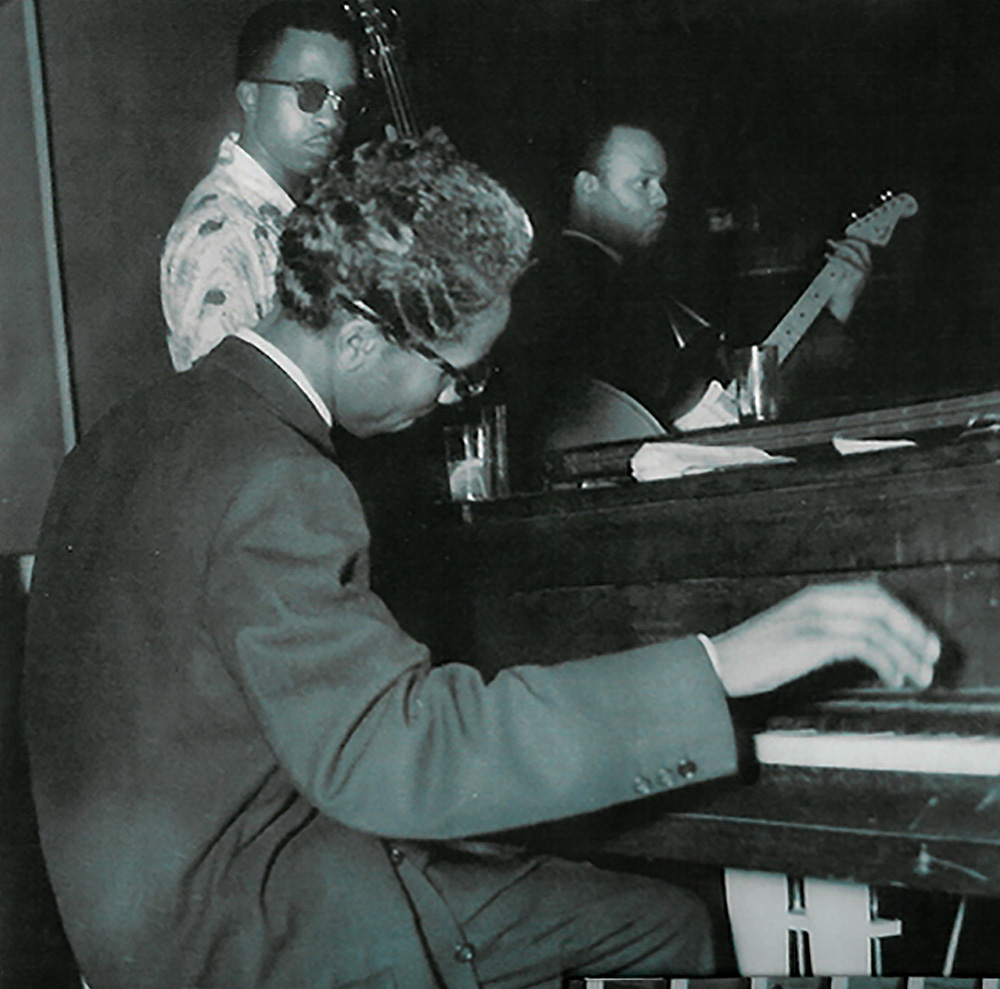

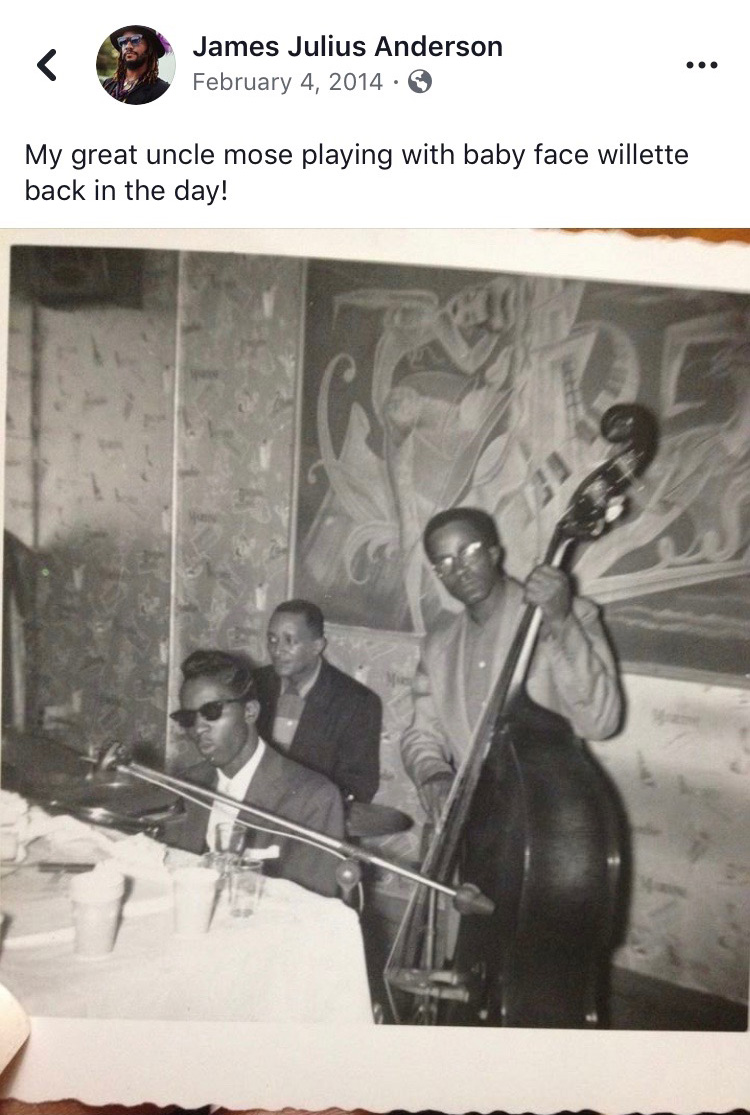

In an undated photo of Willette’s trio – including carpenter turned bassist Moses Weeden (whose name bears an uncanny resemblance to Moses Weedseed, the drummer on Willette’s Vee-Jay session) – posted to Facebook by Weeden’s great-nephew, musician Jay Anderson — Baby Face plays a piano in dark shades and a suit jacket, his hair slicked back.

Despite his dapper approach to his appearance – the thin, 5-foot, 8-inch Willette often dyed his hair a copper color – Gibson recalls him as somewhat reserved.

"Sometimes he would show his feelings in a performance but he didn’t jump around," she told Fallico, calling him, "a very likeable guy. A smart dresser."

"He was very helpful with young people in the community. He wasn’t one that always had something going on. He kept to himself."

When I wrote a shorter piece about Willette many years ago, I spoke to Brew City jazz legend Berkeley Fudge, who remembered Willette, but just barely.

"I thought he was from Chicago," said the saxophonist, after taking a while to answer, carefully considering his responses, and appearing to really scan his memory bank.

"It wasn’t a long time (that Willette was in Milwaukee)," Fudge recalled, noting that he shared the stage with the organist at the Wilson Club on 12th and Center Streets. Also treading the boards was tenor saxophonist John "Wild Man" Gilmore, famous later for his work with Sun Ra.

"At that time the organ was coming back out (in jazz)," he added.

From piano to organ

Willette appears to have switched to the organ, professionally at least, by around 1958, a few years after Jimmy Smith brought the instrument back into the world of jazz, releasing a string of extremely successful Blue Note recordings. Those records inspired many others to pull out the stops and commit to the Hammond B-3, too, including Brother Jack McDuff, Lonnie Smith, Big John Patton, Shirley Scott, Larry Young and others.

In his "Grant’s First Stand" liner notes, Robert Levin recounted that, "Maceo Woods (a church organist from Chicago) and Herman Stevens were responsible for opening his ear to what he termed the 'greater sensational' qualities of the organ and he abandoned the piano in favor of the organ as his primary means of expression. … Jimmy Smith and Shirley Scott (are) his favorite organists. 'Charlie Parker, though, has been my greatest inspiration'."

"He didn’t have his own organ," Gibson recalled. "Most places had an organ already there." When he performed on the road, she added, "He did not travel with his group, he traveled alone and played with musicians in other towns."

According to Chicago guitarist George Freeman, who responded to a query via his friend Mike Allemana, Willette used, "some sort of attachment (that) made the piano sound like an organ." According to Pete Fallico, this is likely the Organo, a device made by the Chicago-based Lowrey Organ Company.

"(It) was an attachment that fit at the end of the lower manual and it allowed the pianist to play a bass line that was similar in sound to the organ bass," says Fallico. "Just about everyone I interviewed from that era admitted they used one."

One such venue with an organ was Chicago’s Crown Propeller Lounge on 63rd Street, a few blocks west of Cottage Grove Avenue, where according to an October 1956 article in the Chicago Daily Defender, "(the) featured instrument at the Crown … a popular 63 Street nightery … is the Hammond organ, one of the finest to be found in any spot."

And a regular there?

"Included on the entertainment menu are such artists as ‘Baby Face’ Willette tonight through Thursday with with several jam sessions on (the) card during (the) week."

Around this time, "Jimmy Smith and Baby Face would play together in little competitions," Gibson told Fallico. "Jimmy would play and then Baby Face would play. The first time, after Jimmy played, Baby Face started playing and Jimmy got up and went over to Baby Face at the organ and said, ‘you take it, I’ll give it to you.’ He loved Jimmy Smith."

Freeman, who recalls performing with Willette at those Crown Propeller gigs, as well as at another venue on 43rd Street, told Allemana that Baby Face was, "a musician ‘who could play.’ That usually means for George that he grooved, swung, had bebop chops and could play the blues."

Around the same time Willette committed to the organ, wrote Levin in his "Face to Face" notes, "he also decided … to devote himself primarily to jazz, which, after hearing several Charlie Parker records, became what he calls his ‘first love.’ But he voices no contempt for rhythm and blues in which he ‘paid his dues.’ On the contrary he believes it to have furnished him with a solid foundation."

"There’s really not much difference," Willette told Levin, "between rhythm and blues and even church music and jazz. That’s where it all came from."

Few who wrote about Willette at the time fail to mention his diminutive stature and his dapper good looks. Those must have been formidable traits in Willette because Fudge conjured those details up, too.

"He was a nice guy. He was a little guy; a little, small guy and he dressed real nice all the time."

Despite his good looks and disposition, Willette, like many who lived the late-night life of jazz clubs of the era, found himself in hot water at times.

Troubled times

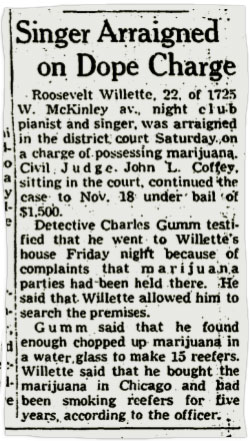

In November 1955, Willette was arrested and arraigned on charges of possession of marijuana in Milwaukee.

According to the Journal, "Detective Charles Gumm testified that he went to Willette’s house Friday night because of complaints of marijuana parties had been held there. … Gumm said he found enough chopped up marijuana in a water glass to make 15 reefers. Willette said that he bought the marijuana in Chicago and had been smoking reefers for five years, according to the officer."

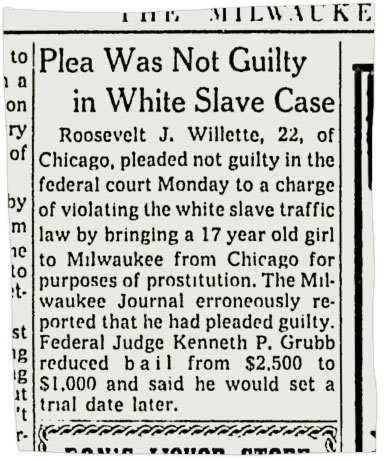

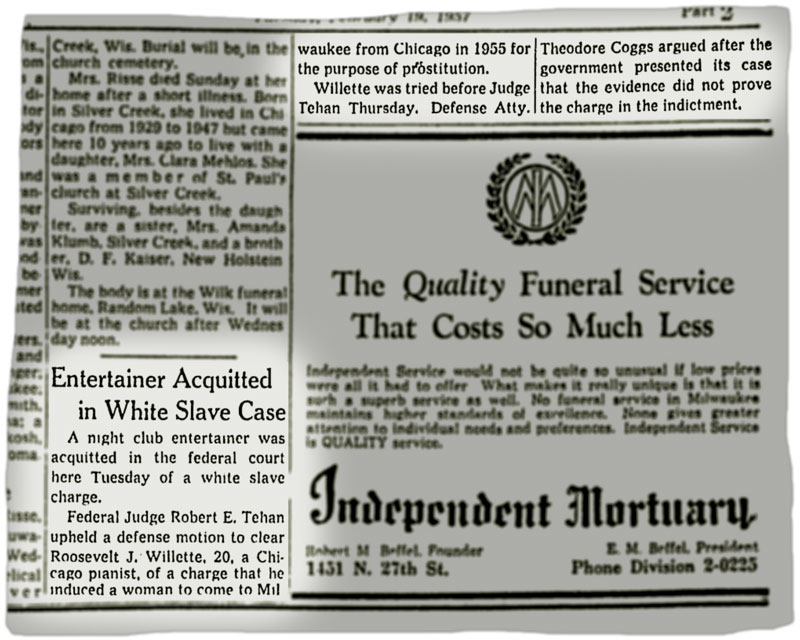

A year later, Willette was arrested by the FBI in Racine on human trafficking charges.

"In a recent federal grand jury indictment," reported the Journal, "Willette, 22, Chicago, was charged with inducing a 17-year-old girl to come to Milwaukee from Chicago to engage in prostitution."

Willette pleaded not guilty and was acquitted, but the case couldn’t have helped his reputation.

Between the two cases, meanwhile, Jo had given birth to the couple’s son, Steven, early in 1956, but soon after Willette was convicted for assaulting Gibson, which likely did irreparable damage to their relationship.

While Baby Face had his career, Gibson had hers, too, traveling to California, where she performed with the Earl Bostic Orchestra and recording for some of John Dolphin’s labels. After the assault, Gibson went back out west in 1958, taking Steven along.

"The only thing I had (of my father's) was the albums," Steven later told Fallico. "We were separated when I was 2 years old … I grew up in California."

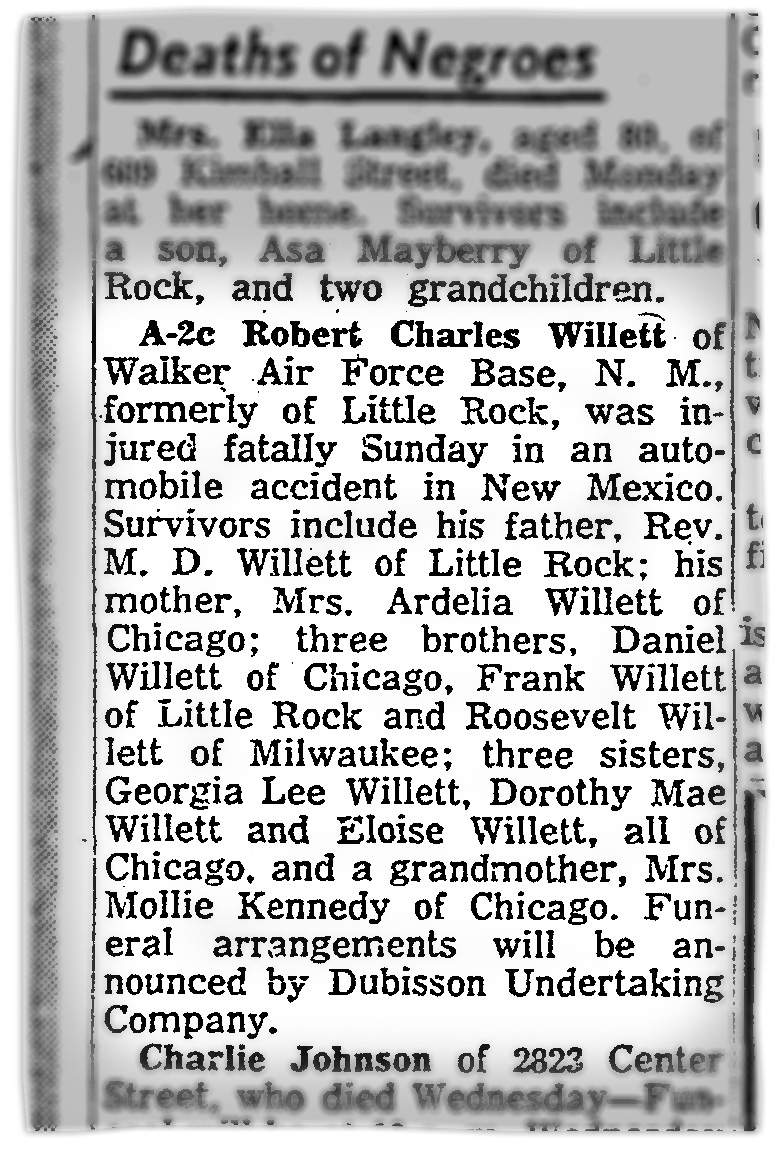

In addition to whatever pressures he may have felt in his relationship with Gibson, Willette was surely affected in these days by family news.

In 1957, his younger brother Robert – an airman second class in the Air Force – died in an automobile crash in New Mexico, where he was serving at the Walker Air Force Base. And at the dawn of 1959, his outspoken father who became known as Prophet Willette on his radio show – broadcast throughout Arkansas, northeastern Louisiana and into Mississippi – was, thanks to his controversial views, embraced by segregationists back in Little Rock.

Meanwhile, in Chicago in late 1959, Baby Face could be found regularly at McKie’s Disc Jockey Lounge in the Strand Hotel at 63rd and Cottage Grove. The area was clearly a locus of jazz and R&B nightlife on the city’s south side.

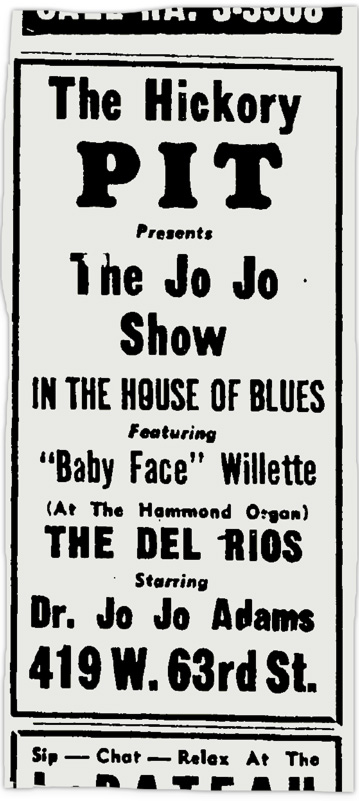

The following March, Willette performed "At The Hammond Organ" on The Jo Jo Show in the House of Blues at The Hickory Pit, further west along 63rd Street, along with jump blues belter, comedian and dancer Dr. Jo Jo Adams and The Del Rios, which included a young William Bell.

In November 1960, still in Chicago and presumably just before he headed east, Willette was arrested on a disorderly conduct charge, the details of which are elusive. But at least some – if not all – of Baby Face’s scrapes with the law throughout his life could have had roots in drug addiction.

Guitarist Freeman told Allemana that Willette was, "battling with heroin addiction (in Chicago). Then George ran into him in New York City, and Willette was really in bad shape physically from the heroin addiction."

The records

Around this time, Willette — who must have been functional enough as a musician, despite his addiction — also toured as a member of the band supporting Brook Benton, who had been making waves on the pop charts since "It’s Just a Matter of Time" reached No. 3 in 1958.

By Jan. 23, 1961, Willette was at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, as a sideman on a session by alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson that would be released as "Here ‘Tis."

"Willette doesn’t play like a lot of organists with a lot of sustained notes," wrote Robert Levin in the original liner notes on the back of the LP sleeve. "He plays a lot more rhythmically."

That style caught the ear of Blue Note’s Alfred Lion and according to Bob Blumenthal, who penned notes for a reissue of "Here ‘Tis," both Willette and Grant Green – the guitarist on the date, who had also recently arrived in New York – received recording contracts from Blue Note after the session.

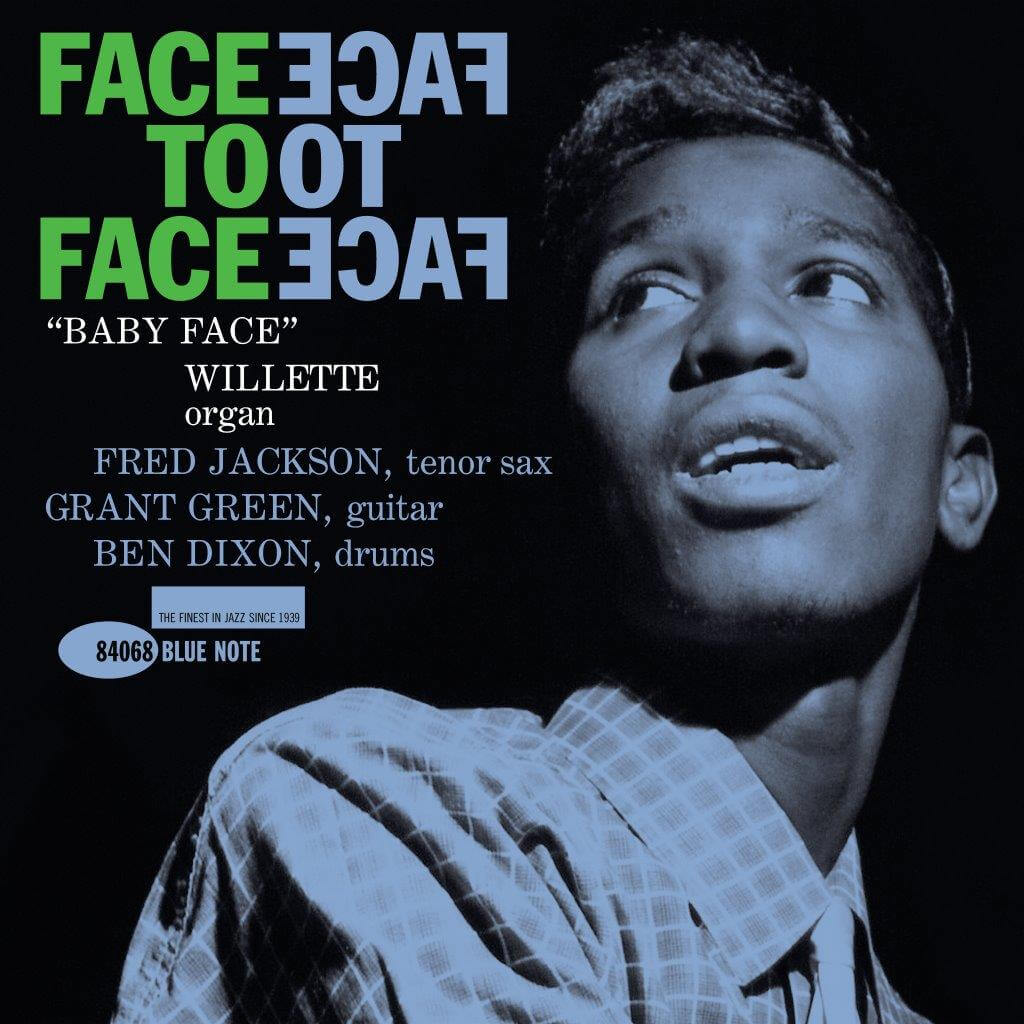

And indeed, both were quickly put back to work, recording Green’s debut as a trio on Jan. 28 and Willette’s – titled "Face to Face," with saxophonist Fred Jackson on tenor – two days later.

Jackson, like Willette, was a veteran of the R&B scene, breaking in as a member of Little Richard’s band in 1951 for two years before moving on to work with Lloyd Price and as Chuck Willis’ bandleader.

All three of these sessions were swinging, funky soul jazz excursions that benefited from the musicians’ backgrounds.

"The common experience which Green, Willette and (drummer Ben) Dixon have each shared," wrote Levin in the liner notes, "and which is revealed throughout the recording, is an extensive apprenticeship in rhythm and blues."

The New York Times jazz critic Ben Ratliff – a Willette devotee – told an interviewer, "‘Face to Face’ transcends the cliches of organ jazz records. There is a drive and a gut feeling on the record – and really excellent playing – that makes you feel that you are not listening to just another organ record. "

Willette, then 28, returned to Englewood Cliffs on May 22, 1961 – again in a trio session with Dixon and Green – to record his second, and final, Blue Note session, released as "Stop and Listen."

Trouble returns

An unemployed Bronx elevator operator named Alfredo Rivera, who was married with four kids, testified that on June 24, 1961 he was approached by a woman who offered to accompany him to an apartment for $5, and that in the building he was confronted by a pair of men, one of whom held a knife to Rivera’s throat while the other robbed him.

Back out on the street, Rivera shouted for help and, followed by a policeman and a witness, chased Willette into a bar. Willette admitted he had a knife and that he’d been at the building, but said that he went inside to protect the woman who was arguing with Rivera. He denied he’d robbed Rivera, saying that he was robbed by a different man.

But Willette was eventually convicted of robbery in the first degree on Dec. 15, 1961 and sentenced to an indefinite term of confinement at Elmira Reformatory in upstate New York. He appealed to the Supreme Court of the State of New York, which upheld the conviction a year later.

So, by the time "Stop and Listen" landed in shops, Willette had already landed in jail.

In court documents filed as part of the appeal, Willette attempted to establish a lack of motive for robbery, and pointed out that he was a musician who had recently toured with Brook Benton, that he played the piano, organ and drums, that he’d recorded for Blue Note, which had paid him $197 for each of the sessions as a sideman and about $280 for each of the two as a leader.

"The defendant had also written songs which were the subject of various recording and publishing contracts. He stated that he sent his wife about $60 a month for support," noted the documents.

At the appeal, Blue Note accountant Moses Roffe testified that in addition to the lump sums noted above for session fees, the label paid Willette $234 in January 1961, $160 in February, $25 in March, $125 in April, $120 in May, $15 in June, $15 in July and $140 in August, presumably mechanical royalties.

He had income, but perhaps it wasn’t enough. Perhaps he’d fallen victim to his addiction. Gibson recalled in her interview with Fallico that Willette was clean (other than the marijuana, presumably), while they were together in Milwaukee. But after they separated, when he was in New York, she said, he was hooked.

"Original annotator Joe Goldberg heard the music on this album as strong evidence that Baby Face Willette would make ‘a continuing contribution,’" wrote Bob Blumenthal in his notes for the record’s reissue on CD. "As things worked out, he barely surfaced again on the national jazz scene."

Would Willette’s career have taken a different path had that June night gone differently? After all, evidence suggests he had been on his way to bigger things.

Life after Blue Note

"Willette had first appeared at the beginning of 1961 as one of Blue Note’s new stars," wrote Blumenthal in those notes on the "Stop and Listen" reissue, "and the empathy he displayed with Grant Green and Ben Dixon here and on the earlier albums … suggested that the unit was poised to become one of the label’s house rhythm sections.

"But Willette had been a creature of the road in his earlier professional life, and chose to travel once again rather than remain in New York," Blumenthal added euphemistically.

In late February 1963, while at Elmira, Willette received news that his father had died at his home at 1118 W. 16th St., in Little Rock, at just 56 years old. Later that year Willette was released from prison and headed back to his family in Chicago and, according to Blumenthal, had "formed a trio and [had] begun appearing in local clubs, including the Moroccan Village."

But if New York’s Blue Note Records had decided to distance itself from Willette and his woes, the Windy City’s legendary Chess Records was willing to give him a try.

In 1964, Chess’ Argo subsidiary released "Mo’ Rock," which was recorded at the label's own Ter Mar Recording Studios in Chicago on March 27 and April 2, with guitarist Ben White and drummer Eugene Bass. The album was named in honor of Moroccan Village, where the trio that made the record had been performing since the previous autumn.

Among the tracks was Willette’s own "Dad’s Theme," which was, according to Willette, quoted in Tom Reed’s liner notes, "a tune that was dedicated to my father, who died recently." In fact, six of the album’s eight tunes were penned by Willette, who had also contributed compositions to his own Blue Note LPs, as well as to "Grant’s First Stand."

On Nov. 30, 1964, Willette and White got back together at Ter Mar, this time with drummer Jerold Donavon – and alto saxophonist Gene Barge on one song – to record "Behind the 8 Ball."

"I called Phil Chess," Barge told the Chicago Reader’s Bill Dahl in 2018, "and he gave me a job on the phone. The day school closed in June ’64, I jumped on a plane and landed in Chicago and began work on Monday morning. "

"Behind the 8 Ball" would turn out to be Willette’s last long-player. Perhaps fittingly, in addition to two Willette originals, the album included performances of two gospel classics: "Amen" and "Just A Closer Walk With Thee," taking his career full circle.

In a brief reference to "Behind the 8 Ball" in June 1965, the Arizona Phoenix Gazette called Willette, "a giant on the organ."

Both sets had been produced by Esmond Edwards, who got his start in jazz working as a photographer for Prestige Records, where he ultimately became a producer.

Edwards, who later became vice president for A&R at Chess, worked with the likes of Ramsey Lewis, Gene Ammons, Coleman Hawkins, and many other jazz musicians, including organists Jack McDuff, Shirley Scott and Johnny "Hammond" Smith, and also with bluesmen like B.B. King and Bobby "Blue" Bland, which may have helped give these records a scruffier, harder wrought edge than the funky, but perhaps more cosmopolitan Blue Notes.

"Willette’s most interesting releases," opined the online music magazine Perfect Sound Forever, "the ones that show him heading into funkier terrain had he found opportunities to record more, are the two Argo releases.

"Whereas the Blue Note releases have the feel of deftly curated club sets, aware of the jazz cognoscenti's gaze, the Argo releases are rawer, rowdier and overtly intend to please those most at home with the sounds found at the populist intersections of gospel, blues and jazz, and out of which soul would arise."

"There is little point in speculating on what happened to Willette (based) on this scant record, but his musical preferences suggest that, had he lived a longer and more productive life, it would not necessarily have been spent as a jazz musician. As both Goldberg and Robert Levin (in the notes to the organist’s earlier album ‘Face to Face’) point out, rhythm and blues and gospel music were Willette’s true foundation," wrote Blumenthal in his reissue liner notes.

"In the end, what might have been cannot detract from what was some very good music that Roosevelt ‘Baby Face’ Willette recorded in Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in 1961. Without a horn soloist in the band, as he is heard here and on the earlier ‘Grant’s First Stand,’ he had no problem carrying the additional solo and ensemble responsibilities, and clearly knew how to set and maintain a groove. It can only be considered music’s loss that Baby never grew up."

It would’ve indeed been interesting to see where Willette’s career would have gone, had it continued, but it wasn’t to be.

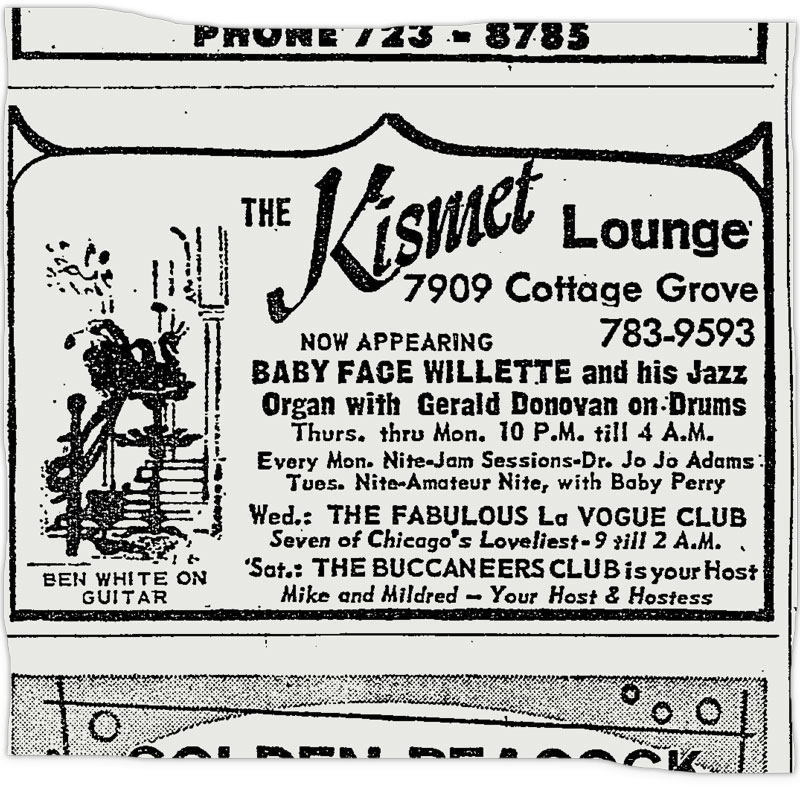

Pete Fallico notes on his Doodlin’ Lounge website that five tracks Baby Face recorded for the Cadet imprint in ’65 remain unreleased, though Willette continued to perform in Chicago clubs. In November 1966 he appeared throughout the month at The Kismet Lounge on 79th and Cottage Grove, with Donovan on the drums.

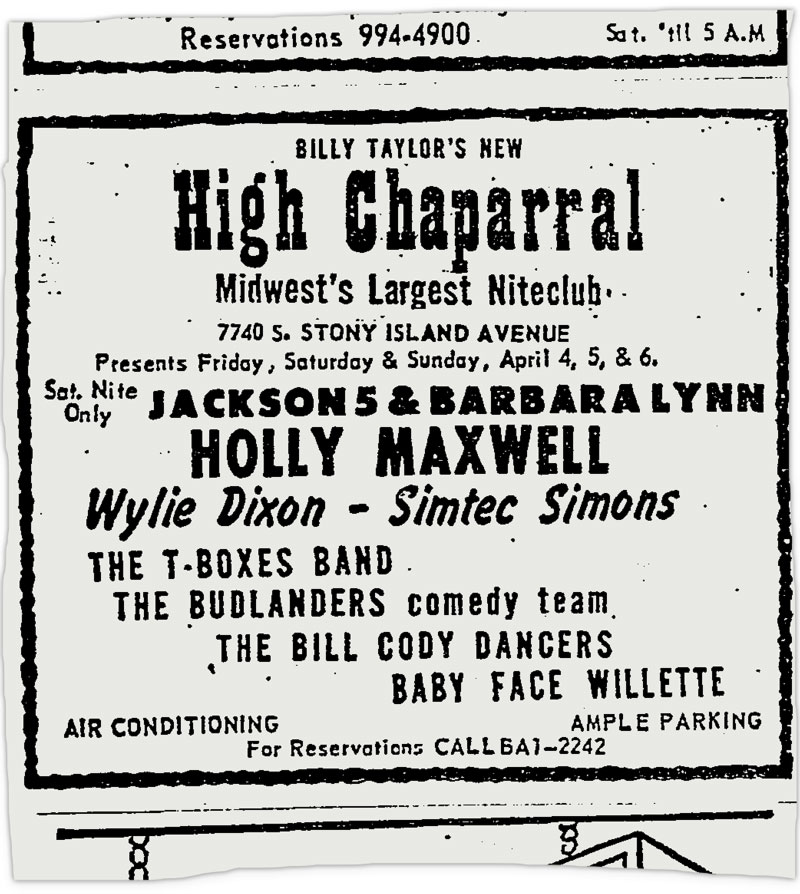

In April 1969, he performed at "Billy Taylor’s new High Chaparral, Midwest’s Largest Niteclub," at 79th and Stony Island Avenue, at the bottom of a long bill topped by The Jackson 5 — who had recently signed to Motown — and Barbara Lynn, that also included Holly Maxwell, Wylie Dixon, Simtec Simons, The T-Boxes Band, The Budlanders comedy team and the Bill Cody Dancers.

On Willette’s artist page on the Blue Note website, Steve Huey notes that Baby Face, "had a regular engagement at a South Side Chicago lounge from 1966 to ‘71 (approximately), but largely vanished from the jazz scene afterward and died in obscurity." It’s possible that this residency was at the Squeeze Club on the West Side, where folks like Buddy Guy and Muddy Waters would play.

"[When] we went back to Chicago to visit his family," Gibson told Fallico. "We ended up at the Squeeze Club and everyone was cheering. He took [our son] Steve and set him on top of the organ. I was petrified, I did not appreciate that. He had to make a spectacle, (but) the people loved it.

"He worked at a club for a long time until he got sick," Gibson continued. "I was on the West Coast and Baby Face came and worked there for a while at that time. I think his health was failing."

During that trip west, which must’ve been around 1968, Steven and his father would reconnect.

"At age 12 I met him," the younger Willette — now a musician, like his father, and a minister, like his father’s father — told Fallico. "One of the most memorable moments of my life. There was a knock on the door and I opened it up and he said, ‘do you know who I am?’ He was playing in L.A. (at the time)."

But it wouldn’t last. On April 1, 1971, Roosevelt James "Baby Face" Willette — who was living at 6509 S. Ashland Ave. — died at Chicago’s Englewood Hospital, of bronchial pneumonia. According to the death certificate, he’d contracted it a week earlier.

Gibson happened to be in Milwaukee visiting family at the time and went to Chicago for the funeral on April 7 at Jerusalem Church of God in Christ and Evans Funeral Home. Baby Face was buried at Burr Oak Cemetery in Chicago. A plaque marking the site reads "Roosevelt J. Willette, brother, 1936-1971."

Though the Argo releases haven’t been reissued – at least not in the United States in a very long time – you can stream "Mo' Roc" on Spotify. Baby Face Willette’s Blue Note sessions can be bought or streamed from the Blue Note website, and are periodically re-released.

In fact, on June 28, 2019, Blue Note reissued "Face to Face" as part of its Tone Poet Audiophile Vinyl Reissue series to celebrate the 80th anniversary of the label. This edition is on 180 gram vinyl and encased in a gorgeous heavy cardboard gatefold sleeve with Francis Wolff photos from the original session.

Around the same time, the label brought out a new vinyl reissue of Grant Green’s "Grant’s First Stand," too.

So, even if the world lost Baby Face Willette too soon, we’re still able to cherish the music.

"It’s like he’s not dead to me," his son Steven told Pete Fallico. "We have a continuing relationship. I listen to his music for inspiration, for knowledge."