This past weekend was the anniversary of an event you have probably never heard of. Well, I shouldn't assume that; I had never heard of it, anyway, and I like to think I'm pretty well versed in knowing things.

May 31-June 1 was the 93rd anniversary of the Tulsa Race Riot, also known as the destruction of "Black Wall Street."

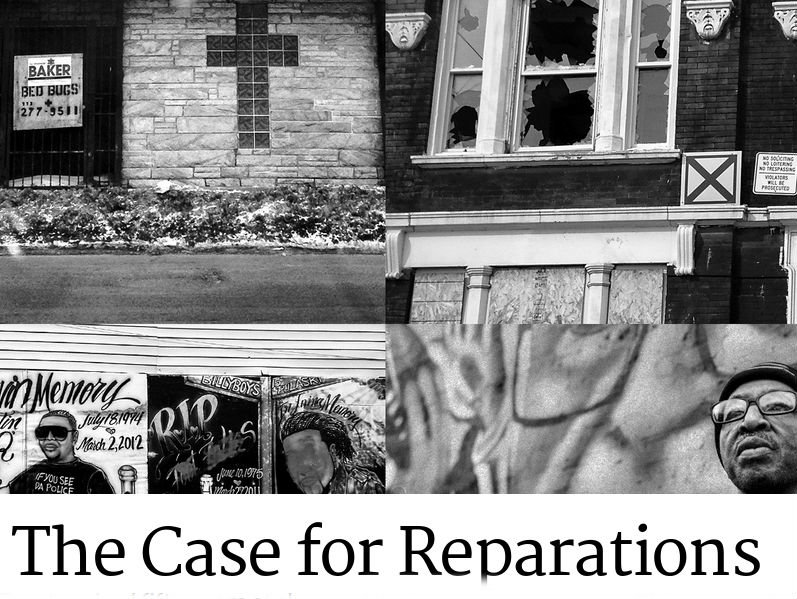

Even though more than 800 people were injured, up to 300 people were killed, 35 blocks of a city were destroyed, and 10,000 people were left homeless -- making it the biggest race riot of the 20th century -- I had never encountered the story until last month when I read "The Case for Reparations," a massive and thorough argument by The Atlantic's Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Generally, in fact, when I have heard about America's race riots, I have only heard about those in the latter half of the 20th century, in which the perpetrators of the riots were African Americans and the victims were white, like Milwaukee's 1967 riot, or the Watts riots in Los Angeles. In the Tulsa Race Riot, white residents of the city completely destroyed what was, at the time, the most prosperous black community in the United States, burning it to the ground, something I had never learned about in school or since.

Part of this, I'm sure, is the recency effect; the more recent things are the things we remember best. But I'm also sure part of why I'd never heard of it is because this country likes to pretend that white America -- which is what most people think of as the default "America" -- bears no social, political or financial responsibility for the current state of black America.

The Tulsa Race Riot is just one data point of many Coates uses to build his case that the segregation, poverty, educational failure, and crime suffered in African-American communities around the country are not accidental. Indeed, once you start looking, you find there are hundreds of other such riots all over the county, from reconstruction to the Civil Rights era, each one destroying masses of accumulated black wealth and driving the exclusion of blacks from white communities and centers of commerce.

Coates writes about Chicago, in particular, and not just its white-on-black riots, but the way private enterprise and the government at all levels worked to keep black residents segregated and poor, through legal redlining and outright theft.

While Chicago and the South rightly loom large in Coates' piece, Milwaukee has its own history of redlining, the practice of racial segregation in housing, so-called because it began, literally, with the Federal Housing Authority literally drawing red lines around black neighborhoods on maps. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 -- within the lifetimes of much or my readership, I'm sure -- ended legal redlining, but not the practice.

It's been less than 20 years, in fact, since the end of a major lawsuit against Milwaukee's American Family Insurance for refusing to write homeowners insurance policies in predominantly African-American neighborhoods of the city. The settlement was a paltry $16.5 million, a ridiculously low price to pay for enabling the creation of America's most segregated metro region.

Today, things are not much better. Recently we learned Milwaukee is the worst major city for homes underwater, in default, or in foreclosure. We know -- because the federal government is now prosecuting offending lenders, rather than providing them legal cover -- that major lenders like Chase, Bank of America and Wells Fargo targeted African American neighborhoods with subprime loans.

Milwaukee's "zombie houses" are concentrated in poor, primarily black neighborhoods in the city. Again, this did not happen accidentally, the same way the Tulsa Race Riot was not accidentally left out of the history books.

Coates scrupulously details America's abysmal racial history, connecting the dots to show that 435 years of slavery, Jim Crow, pre-Brown education, and housing discrimination, perpetrated by or allowed to happen by the white majority in this country, have directly led to the perilous conditions in which African-Americans currently live. His argument is persuasive.

How reparations would happen in practice is its own thorny question. As we've discussed, I'm not an economist, so I can't say exactly how to or how much. I'll leave that to others.

I haven't intended to keep writing here about race, and I'm a pretty unlikely candidate to be OnMilwaukee.com's "race guy." I mean, see my picture up at the top of the page? Camera guys use my face to set their white balance.

But I do feel it's important to have this conversation. None of us on either side of the keyboard have ever owned slaves, and most of us, I imagine, don't engage in specific interpersonal moments of racial discrimination.

But as Peggy McIntosh has eloquently written, "In my class and place, I did not see myself as a racist because I was taught to recognize racism only in individual acts of meanness by members of my group, never in invisible systems conferring unsought racial dominance on my group from birth."

It is clear from Coates' essay, and from just a cursory reading of the history of this country -- this city, even -- that there has long been an invisible system at work. Reparations is one way to address the devastation that system has caused.