Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part special report from Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service on Milwaukee’s charitable food programs. Part one focuses on how cuts to federal aid are affecting food banks, pantries and hot meal programs. Part two is available on Milwaukee NNS' website.

For many Milwaukeeans, hunger is an unfortunate reality of life.

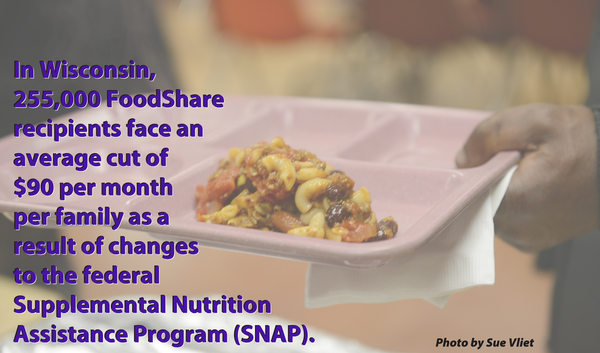

The lingering effects of a sluggish economy, paired with recent cuts to the federally funded Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) — known as FoodShare in Wisconsin — have caused many to rely on a network of food banks, pantries and hot meal programs that are trying to meet the growing demand while advocating for additional aid.

Judi Bartfeld, food security research and policy specialist at University of Wisconsin-Extension, explained that the recent cuts to FoodShare stemmed from two changes.

In November 2013, temporary benefit increases to SNAP from the 2009 American Recovery and Relief Act were abruptly ended. Bartfeld noted that the original intent was to gradually phase out the increased benefits through 2015.

Also, Bartfeld pointed to the 2014 Farm Bill, which redefined how net income is calculated for SNAP households receiving aid from the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program. The new calculations reduced SNAP benefits nationwide by about $8.6 billion over the next decade. In Wisconsin, 255,000 FoodShare recipients face an average cut of $90 per month per family, totaling about $276 million over the course of a year.

In addition, Gov. Scott Walker’s proposed 2015-2017 state budget threatens the accessibility of food-related aid. The governor has proposed legislation that would require drug testing of able-bodied FoodShare recipients enrolled in the FoodShare Employment and Training Program (FSET). Critics claim that the drug testing would violate the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits search and seizure without probable cause.

Also, beginning April 1, a state exemption to federal work requirements for food assistance instituted during the 2008 recession will end. Eligible adults without dependents will be able to receive FoodShare benefits if they are working 80 hours per month or participating in the FoodShare Employment and Training Program. If they do not meet those requirements, they can only receive food assistance for a three-month period every 36 months.

Milwaukee’s food-based charities offer a helping hand to those affected by the FoodShare cuts, such as Judy Johnson, who frequents the community meal program at The Gathering on 833 W. Wisconsin Ave.

Johnson, 58, relies on disability checks and food stamps through FoodShare, which were reduced from $155 to $31 per month in 2014.

"I’ve been up and down," said Johnson, who has struggled with a recent string of health problems. "I had been on the streets for a while, behind the Grand Avenue mall, but I have a studio now."

To make up the difference, Johnson often eats breakfast at The Gathering and dinner at St. Benedict the Moor, 924 W. State St. She also has started going to Ebenezer Lutheran Church food pantry, 1127 S. 35th St., where she typically receives canned and dry goods, some fruit, a package of meat and a few toiletries.

"You gotta do what you gotta do to eat," Johnson said. "Sometimes that means robbing Peter to pay Paul. If you do that every month, then you’re playing catch up, and you’re going to get behind."

Johnson’s experience is typical of those living in poverty in Milwaukee. According to the latest census data, nearly 30 percent of the population residing within city limits is impoverished, which is almost double the national percentage.

About 37 percent of Milwaukee County’s population is enrolled in FoodShare. This figure has more than doubled since 2000, when only 16.8 percent of the population received the monthly assistance.

"Hunger is a symptom of poverty," explained Sherrie Tussler, executive director of the locally operated food bank, Hunger Task Force. "Everyone understands hunger because we all feel it."

About 50 million Americans and 30 percent of families identify as food insecure, meaning they lack resources for consistent access to food, according to the most recent U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data.

Assessing the need

Milwaukee’s network of food pantries and hot meal programs relies on the area’s largest food banks, Hunger Task Force and Feeding America Eastern Wisconsin, to keep their doors open and shelves stocked.

Feeding America Eastern Wisconsin, the regional member of the national network of food banks, and Hunger Task Force collectively distributed about 16.4 million pounds of food last year. The food comes from a variety of sources, ranging from individual donations to partnerships with national corporations, and feeds countless individuals throughout the community.

About 250 programs in the county utilize resources at Feeding America, while a network of 80 charitable food programs rely on the free donations from Hunger Task Force.

All of the programs depend on volunteers to operate. In 2014, the Hunger Task Force reported that 79 different volunteer groups sorted more than 1.5 million pounds of food. At The Gathering, volunteers provide 98 percent of direct service to guests and nearly 33,000 hours of service were logged in the 2013-2014 fiscal year.

It’s not just church groups and youth programs volunteering. Many of Milwaukee’s businesses and nonprofit organizations make it a point to lend a helping hand.

"It’s great to do something for our community," said Kevin Buss, assistant director of strategic intelligence at Northwestern Mutual. Buss and his team volunteer at Feeding America sort through donations and repackage them for distribution.

About 6,000 volunteers worked nearly 18,000 hours at Feeding America Eastern Wisconsin in 2014.

Volunteers make it possible for programs to feed a staggering number of people. For example, The Gathering served 6,790 meals in January; St. Benedict the Moor averages about 10,000 meals per month.

Ideally, it would be unnecessary for meal programs to provide such a large number of meals. Food-based charities were originally organized to help during times of crisis, but due to widespread poverty and the drop in FoodShare benefits, today many people regularly rely on the charities. According to a national survey conducted by Feeding America, one in seven Americans visited a food pantry in 2013.

Accessing aid

In 2013, 83 percent of students at Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) qualified for free or reduced-priced meals through the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, enacted in 2010. Prior to the start of the 2014-2015 school year, CEP required Wisconsin parents to fill out an application that documented their participation in FoodShare. The application process was a hurdle that often deterred students from receiving free lunches.

Today, the district participates in the National School Lunch Program, and parents are no longer required to fill out the free meal application. Statewide, nearly 750 schools qualified for CEP and 355 enrolled.

"Having every student come to school well nourished and ready to learn is absolutely critical to students’ well-being — and it’s critical to our work to improve student outcomes," said Darienne Driver, MPS superintendent, in a news release.

While expansion of CEP made it easier for Wisconsin students to get free meals at school, the recent cuts in FoodShare benefits diminish the gains.

Typically, there are about 2 million pounds of food in the Feeding America warehouse at 1700 W. Fond du Lac Ave. and the group distributes 70,000 pounds each day to nine Wisconsin counties.

In 2014, Milwaukee County received the most FoodShare benefits of all Wisconsin counties, nearly 38 percent of the roughly $1.1 billion total aid distributed statewide.

Another federal program affected by the Farm Bill is The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), which is a USDA program that provides federal commodities to food pantries and hot meal programs. Nationwide, the Farm Bill will increase TEFAP funding by $205 million through 2023.

The Hunger Task Force administers TEFAP in Milwaukee County. In 2010, the supplemental commodities accounted for 35 percent of the total food it distributed. The commodities also help fill the Hunger Task Force’s Stockbox program, which delivers a box of healthy foods to about 9,000 low-income senior citizens each month.

Program directors at food-based charities are finding that many clients qualify for more help than they are receiving. Research conducted by the Hunger Task Force found that up to 90 percent of pantry clients are eligible for FoodShare, but less than half participate. The studies also found that many qualified applicants are not applying for other aid programs such as Medicaid, tax credits and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

"We want our pantries to talk to people about their conditions so that they can use the federal programs," Tussler said. For example, she mentioned that schools could provide 15 of a child’s 21 weekly meals. Then food stamps could more adequately cover the weekly grocery bill.

"We teach our pantry coordinators all of this stuff about how these programs work so that they can encourage and help and support [people] so that we don’t create a generation of people who think the church is a store," Tussler noted.

For Tussler, the key to making significant changes and reducing the reliance on food-based charities is community advocacy.

"Why don’t we do something about the poverty in the neighborhood? Why don’t we deal with systemic issues? Why don’t we vote differently?"

Rippinger attended Saint Louis University, where she earned a degree in communication with an emphasis on journalism and media. Currently, she is a master's degree student at the Diederich College of Communication at Marquette University.