Obviously P.D. McCartin didn’t read the Police Gazette or whatever was the 1916 equivalent of People magazine, because he had no idea that Harry Houdini was one of the biggest celebrities in the world.

Chief McCartin, head of the fire department in Colorado Springs, Colo., didn’t even know who the performer billed as "Houdini the Great" was.

But when McCartin was standing outside his firehouse late one day that fall and saw strolling down the street the man who was in town to enthrall another theater crowd with his ability to squirm out of a straightjacket, a chained and padlocked trunk and the stoutest handcuffs that could be found, something about him rang a bell.

McCartin approached him and said, "Pardon me, but isn’t your name Weiss?"

"It is," replied Houdini, whose straight handle was Erich Weiss, "but I do not remember you."

"You fought for me several times," said McCartin. "I used to run bouts in the basement of the Kirby House in Milwaukee in 1886. Mickey Riley was one of my best performers. One day he said he had a likely looking chap in tow. He brought you in. I remember you gave Mickey a bad licking and earned the dollar that went to the winner."

Houdini’s surprise reunion with Patsy McCartin – one of Milwaukee’s top boxers in the 1880s – was recounted by the renowned escape artist to Milwaukee Sentinel sportswriter J.J. Delaney when Houdini was in town in March 1916 for a week’s engagement at the Majestic Theater.

Born in Budapest, Hungary on March 24, 1874, Houdini was 4 when his family landed in Appleton. The Weisses moved to Milwaukee in 1883, and Erich teamed up with Adonis Ames, a local contortionist, when both were newsboys hawking The Milwaukee Journal on Downtown street corners.

They performed for free on the Wisconsin Avenue bridge over the Milwaukee River, and later Weiss did magic tricks at Jacob Lett’s dime museum at 132 W. Wisconsin Ave.

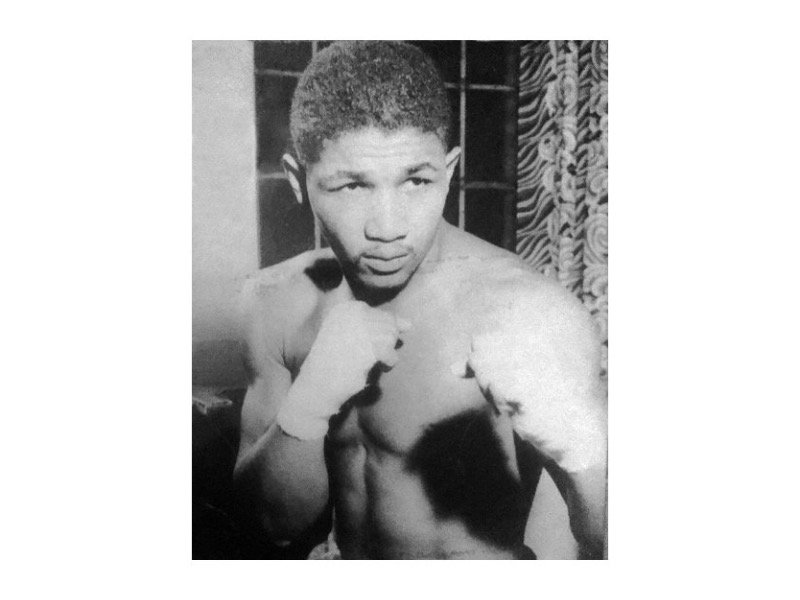

The athletic Houdini-to-be kept in shape by running track, swimming and boxing for McCartin at the Kirby House (a hotel at the intersection of Water and Mason Streets) and later he gave bicycle racing a try in the annual Waukesha Road Race from the Waukesha Court House to 28th and Wisconsin.

When he returned to Milwaukee to perform at the Majestic in 1916 as Houdini, he was pulling in $3,000 a week (almost $67,000 in today’s dollars), and still basking in the acclaim resulting from one of his most stunning feats – turning a towering American icon into a national laughingstock.

On Dec. 1, 1915, Houdini was headlining at the Orpheum Theater in Los Angeles. As he did everywhere he performed, Houdini picked 10 persons from the audience to come up on stage and attest that the straitjackets, handcuffs and other implements of imprisonment used in his act were not rigged. But this time, after seven men had been selected for the task Houdini stepped to the footlights for a special announcement.

"Now I need three more gentlemen on this stage and there is a man here tonight who doesn’t know I am aware of his presence," he said. "He will be enough for three ordinary gentlemen if he will serve on this committee. He is Jess Willard, our champion."

Jess Willard had become the most famous and popular athlete in the world the previous April when he won the heavyweight boxing championship by knocking out Jack Johnson in 26 rounds in Havana, Cuba. Known as "The Pottawatomie Giant," the 6-foot, 6 ½-inch, 230-pound Kansan was considered the epitome of rugged manliness.

After he won the title Willard moved to Los Angeles, and when the Orpheum audience heard from Houdini that the greatest boxer of them all was in their midst, reported the Sentinel, there was "tumultuous handclapping" and "cheers and shrieks resounded throughout the house."

"I will leave it to the audience, Mr. Willard," declared Houdini to even louder cheers. "You see, they want to see you."

Seated in the balcony, Willard’s reaction was to growl, "Aw, g’wan with your act. I paid for my seat here."

When Houdini good-naturedly tried again, the glowering Willard said, "Give me the same wages you pay those other fellows and I’ll come down."

The audience of about 2,000 was stunned into silence.

"Come on down," Houdini said less genially. "I pay these men nothing."

Willard gruffly refused again to scattered hissing and booing. Then Houdini drew himself up to his full 5 feet 6 inches and held up a hand for quiet.

"I was mistaken," he said. "I called for gentlemen, Mr. Willard, but you are not one. Now I want to tell you something else. Remember, I will be Houdini the Great when you are no longer heavyweight champion!"

The cheers sparked by Houdini’s rhetorical haymaker were so thunderous that Willard fled the theater. The public derision engendered by the incident caused the heavyweight champion to eventually decamp from Los Angeles.

First, though, he whined in a letter to the L.A. Examiner:

Because I would not make a personal appearance on the stage to strengthen the performer’s moth-eaten act, the press agent of the theater rushed to the penny papers and got more publicity than he usually gets in a year. All this because of the position I happen to occupy in public life. When I declined to come down to the stage, this should have settled the matter and the stage ‘hero’ should have gone on about his work. The only reason in the world he ‘worked up a scene’ was because he knew my name would be a boost for him… I do not believe that the laws of California permit of a theatrical management singling out a patron for the abuse that I have had to stand.

About three years later, Willard was training to defend his heavyweight title (unsuccessfully) against Jack Dempsey in Toledo, Ohio.

While boxing with sparring partner Walter Monohan, the champ’s eye was cut and a spectator yelled, "What a big ham you are, Willard! You’re a big bum when a little guy like Monohan can cut your eye. What will Dempsey do to you?"

The crowd laughed, enraging Willard. "If any of you fellows out there think you can do as much to me or more than Monohan," he roared, "step right up and take a crack at me!"

Lucky for Willard that his Milwaukee nemesis Erich Weiss – dead 87 years ago this Halloween and the subject of a History Channel miniseries currently in production – wasn’t around to take him up on it.