1. Everybody was lined up at the bubbler, and then everybody was lined up to go to the bathroom

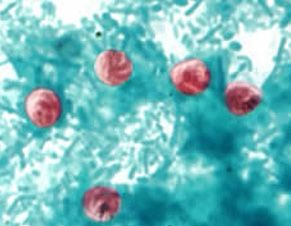

Photo © Center for Disease Control

Nathaniel Bauer had no idea how he was going to get through baseball practice.

Back in the spring of 1993, Bauer was a sophomore at Wisconsin Lutheran High School. Indoor baseball practice had recently begun inside the school’s gymnasium, but Bauer was struggling to make it through. His guts felt like they were fighting against him.

Bauer wasn’t the only one on the team suffering from some mysterious stomach ailment. Their early attempts at solutions certainly weren’t working.

"Nobody really knew what was happening," Bauer said. "They just said, ‘Hey, drink more. Drink more water out of the bubbler.' So everybody was lined up at the bubbler just drinking water, and then everybody was lined up to go to the bathroom."

It wasn’t just the baseball team. Half the school was doubled over, as was Bauer’s family. Soon, the city was ailing, emptying drug stores of toilet paper and Imodium.

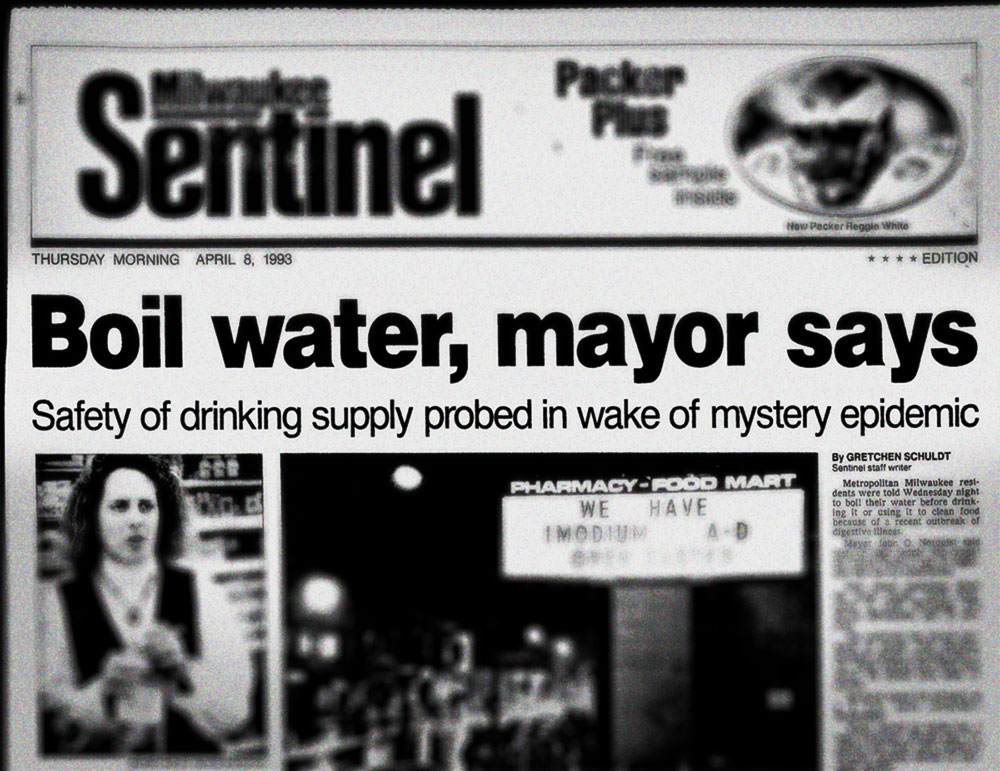

Eventually, orders came down from the health department and government: This is no ordinary flu; it’s the water.

"It was kind of one of those things that nobody expected or anticipated, and nobody kind of really knew how to react," Bauer said. "Wait a minute; it’s in the drinking water?

"It took a few days for everyone to be like, 'Yeah, this is really the case: Don’t drink the water.'"

A boil advisory was soon imposed.

The truth was becoming all too apparent: A pandemic breaking out in Milwaukee, one that would infect approximately 403,000 citizens and lead to at least 69 related deaths within a few weeks. Eventually, the microscopic culprit’s name was uncovered – cryptosporidium.

Now, as Ebola grips the national mindset, with perceived blunders in Texas and New York, the lessons learned during those weeks in 1993 will be just as important for another potential outbreak more than 20 years later.

The cryptosporidium outbreak is still fresh in the memory of Paul Biedrzycki. The current director of disease control and environmental health for the City of Milwaukee Health Department – at the time the city's environmental health manager – remembers the panic, the boil water order, the signs saying "No Imodium" in front of drug stores, the telltale signs that look so obvious now in perspective.

Two decades after, he still gets questions about crypto in Milwaukee, namely in the post-Sept. 11 bioterrorism age.

"If you look back at what happened with crypto, it was an emerging infectious disease that was not on our radar," Biedrzycki recalled. "It did not have a high case fatality rate, but it was unknown in terms of the epidemiology – like who was most at risk, how this would play out in terms of the trajectory of the illness, how many people would get sick and what it would do to health care capacity."

Biedrzycki still talks a lot today to health departments and researchers hoping to learn from Milwaukee’s handling of cryptosporidium – a naturally occurring event – in the hopes of preventing future outbreaks and especially thwarting bioterrorists using water as a conduit.

For the long-time public health worker, however, there are even more important lessons to be learned from the ’93 outbreak, ones that aim to make the Health Department more efficient at handling future pandemics and keep the city safe.

One of the biggest problems in cracking the crypto outbreak was a lack of communication between multiple parties – water utilities, public health and other stakeholders – about the growing number of red flags popping up in early spring of that year.

"I was there; the personal examples of dealing with water plant engineers who basically said, ‘Nothing's wrong with the water; it's operating according to standards,’" Biedrzycki said. "I know what they're saying, but what if it's a bug that falls beneath those standards? You're operating, your turbidity is fine, your chlorine residuals are fine, but what if it's resistant to chlorine and doesn't show up as turbid water? And they couldn't imagine that."

Later, when the Health Department looked through the Water Works' complaint logs, it discovered a significant spike in complaints around the start of the outbreak. For the Water Works, however, that spike was easily shrugged off: When the lake turns over in March, they argued, you get algae odor. The plant adjusted, and the complaints went no further.

All the while, the Health Department and Water Works were in the same building, separated by a mere three floors. Biedrzycki would even pass the Linnwood treatment plant manager in the cafeteria without any words spoken about troubling water trends or the sickness quietly escalating in the city, save for one conversation.

The plant manager phoned Biedrzycki to ask if Milwaukee was currently dealing with an uptick in flu cases. Biedrzycki didn’t know and recommended the manager ask their virologist. Months later, he put the pieces together.

"He was trying to understand if the stomach flu was in a certain part of town because there were getting lots of complaints," Biedrzycki noted. "So that was probably an early call to me, but I didn't recognize it. He was asking about the flu. I had no idea, and it was late in the flu season. I sent him up to our virologist and never heard back. So, in retrospect, that could have been an early signal that I failed to recognize because we had no relation with the Water Works, and he gave me no other additional information."

As a result of flawed communication and partnerships, it took public health and the Water Works more time to discover and lock in on the water contamination. The event is said to have occurred in middle-to-late March; the eventual boil water advisory didn’t arrive until the first weekend of April.

"That was a big lesson," Biedrzycki said. "We didn't have those relationships. Not having those relationships made response extremely difficult. In fact, some people would say that if we had those relationships, we would've been able to detect the water contamination event weeks – literally weeks – earlier."

"If you don’t share information, you become silo-ed. Public health was a silo back then. We're not silo-ed anymore."

Now, the painful lessons learned in the crypto outbreak – "a pioneering event," Biedrzycki calls it – have led to improved communication and relationships between different parties. In the case of similar events, such as the isolated Ebola cases currently in the U.S., public health reaches out to non-profits, the private sector, utilities and other stakeholders for information. Improved partnerships have also been established with pharmacies, emergency departments, poison control centers and ambulance companies.

The Department of Public Health also makes greater use of a process called syndromal surveillance, a way of monitoring public behavior – an explosion in people purchasing a certain product, increased absenteeism at work, increased ambulance runs, social media – to help uncover an outbreak in progress.

In the case of cryptosporidium, Biedrzycki and public health were clueless about the frantic Imodium purchases from drug stores until several weeks into the outbreak.

"We had no idea that was occurring," Biedrzycki noted. "We looked then at nursing homes, places with captured institutional populations: a lot of diarrhea. We then contacted large businesses that said, ‘Yeah, we've seen 15 to 25 percent absenteeism the last couple of weeks.’ We have to take all of those signals and then look at them comprehensively to make a decision whether or not there might be illness. But that becomes a trigger then for investigation."

Syndromal surveillance signals can help provide a picture, but Biedrzycki noted that the resulting data is often "noisy," filled with false alarms, inaccurate or irrelevant information.

What got public health investigating crypto back in 1993 wasn’t syndromal surveillance; it was a call from a physician reporting a case of crypto in a non-immunally compromised patient.

"That's how I get turned onto these things, not through syndromic surveillance or lab specimens that are weeks old," Biedrzycki said. "We have better relationships and I'm confident that if they experience a surge, that they would call us or contact us. It's a big difference. Partnerships mean information sharing. Partnerships mean trust where you want to immediately share information. Without that, nothing good can happen."