Brewmasters tap into Milwaukee’s beer-making tradition

The men who make the beers that made Milwaukee famous

Looking at the landscape, you’d think that – to paraphrase Rod Stewart – what made Milwaukee famous also made a loser out of Brew City.

What’s left of Schlitz’s sprawling complex is now office space. The old Pabst Brewery is a hotel, apartments and offices. The surviving Blatz brewery buildings house residential units and a college campus. The old Falk Brewery, on the edge of the Menomonee Valley, is empty and crumbling. Husting’s brewery in Haymarket Square still stands but no beer is made there. And even the Gipfel Union Brewery – long acknowledged as a remnant of the city’s proud beer-making tradition – was erased years ago now.

But you’d be wrong.

Brewing in Milwaukee thrives today and at a range of levels, from homebrewers to craft beer producers to major breweries.

Scratching the Itch

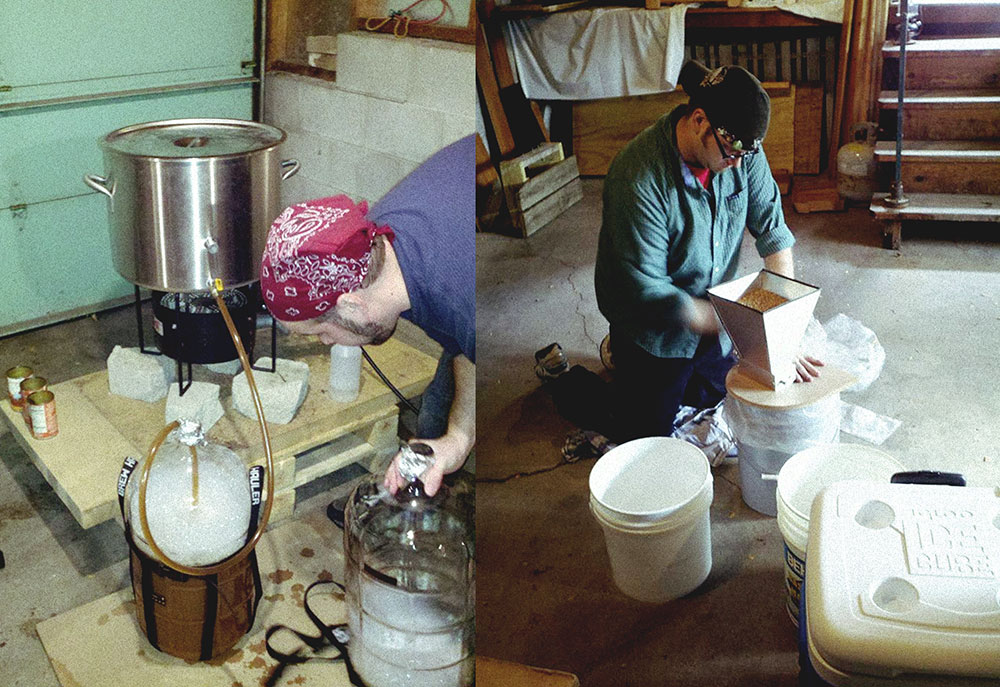

Some – like Jared Sutliff, who is president of the Beer Barons homebrewing club – make a barrel at a time in their basements. Mike Brenner, who opened his craft brewery in Walker’s Point last year, cooks up 30 barrel batches of roughly seven beers every few weeks.

Meanwhile, over at 10th Street Brewery, Dave Hansen and his colleagues at Leinenkugel’s brew 30,000 to 35,000 barrels each year. And Leinie’s parent company, MillerCoors, makes 10 times that amount every single day under the supervision of Dr. David Ryder down in the valley.

Despite the differences in scale, all these brewmasters share a basic love for the work and for the results.

"I remember the first time my brother made a batch of beer and gave me a bottle. As soon as I tasted it, I was hooked," recalls Sutliff, who says making beer at home is easy and rewarding.

Sutliff says a homebrewer can get started on a five-gallon batch of beer with an investment of $150 or less. And the work can be extremely rewarding.

"If you are someone who likes to make things yourself, you would like to homebrew," he says.

For many brewers, making beer at home and enjoying it with friends is enough. But, for others, like Dr. David Ryder, the internationally respected brewmaster at MillerCoors, making beer is an itch that requires more intensive scratching.

"I started off in the malting industry, turning barley into malt," he recalls as we sit in the small pilot brewery located above the massive Miller brewhouse. "Beer seemed intriguing, so I decided I was going to travel to Africa… in this case I went to South Africa, and joined the breweries there … and haven’t stopped since."

Leinenkugel’s Dave Hansen took a more traditional approach to a career. He studied at university.

"This is my first brewing job," says Hansen, who hails from Madison and came to Milwaukee after earning a master’s certificate in brewing from UC Davis. "I came back home and took a job as a bar manager and then our former brewmaster, Greg Walter, was like, ‘Hey, he’s local. Bring him in for an interview.’ It worked out nicely (for me)."

On the other hand, Mike Brenner’s decision to throw himself lock, stock and barrel into brewing – a process he launched by first earning an MBA and then heading to Germany to study beer-making – is rooted in a European tradition in which making beer for profit has been a means to support other more philanthropic work.

Brenner drew off his German experience touring European breweries, where he learned that for centuries monks brewed beer to support their missions. It inspired him. For Brenner – who founded and ran Milwaukee Artists Resource Network and also ran a small Riverwest gallery – brewing was a means to support the arts.

"The idea of this place," he says of his Walker’s Point brewery, "is to really support the community. Beer money has paid for arts and culture in this city since the beginning so, I thought, ‘why don’t I just take this hobby and make it a career?’"

In addition to brewing and selling beer, Brenner Brewing hosts exhibitions for artists and a range of other arts-related events.

Last month, Brenner Brewery was named Best New Wisconsin Brewer by RateBeer.com.

While most every aspiring guitarist yearns for the spotlight, you might be surprised to learn that the same isn’t always true in the world of beer. Each homebrewer, says Sutliff, brings his own expectations and aspirations to the craft.

"Some of us look up to the pros and try to ‘clone’ the commercial beer as a nod to the innovation and creativity of the flavor we love so much," says Sutliff. "Some of us only want this as a hobby to hang out with friends and create something tasty. Some of us actually want to pursue brewing as a career and what better way to do that then actually make the product and take it to brewers to taste and evaluate.

"So like any hobby, there are the ones who enjoy the process, camaraderie, challenge, competition or actually aspire to become one of the legends."

The Milwaukee tradition

There is no shortage of legends in Milwaukee brewing, from Fred Miller to Capt. Frederick Pabst to Joseph Schlitz and beyond. That’s because, thanks in large part to Milwaukee’s German heritage, it’s always been a beer town.

The city’s brewing story – and Wisconsin’s, too – begins in 1840 when Richard Owens, Williams Pawlett and John Davis – Welshman one and all – made their first batch of beer in July at their brewery along the lakefront at Clybourn Street, using a wooden box lined with copper as a five-barrel brew kettle.

Three years later Johann Christian David Gipfel established his brewery at 4th and Juneau and in 1844 Jacob Best launched the brewery that would become Pabst. In 1850, Val Blatz opened his brewery, and by 1855, Fred Miller had arrived from Germany and set up shop, and Falk began brewing beer that year, too. Schlitz opened in 1858.

Many others would come and go over the years, but the big boys not only endured, but grew into industry giants over the following century, helping to solidify Milwaukee’s reputation as Brew City USA.

Though all but Miller have shut down their local operations, a wide range of players, including Sprecher, Lakefront, Horny Goat, Milwaukee Brewing Co. and Brenner Brewing, have helped keep the city’s beer flowing.

And today’s brewmasters understand the tradition and identify with it, even if sometimes they don’t feel worthy.

"I do feel some sort of connection to Milwaukee’s beer making past," says Sutliff. "The younger craft breweries in Milwaukee – Lakefront, Milwaukee Brewing Co., etc. – started off as homebrewers early in the craft beer boom. Now they are making some of the best beers around. The original Beer Barons helped grow our great city to what it is and as a nod to our past, it feels good to create your own."

Milwaukee is a key part of the equation for Mike Brenner, who says he turned down lucrative offers to establish his brewery in the suburbs.

"I was like, ‘it’s gotta be Milwaukee. I’m not doing this anywhere else,’ he recalls. "It’s important to me to be a part of that brewing tradition."

Over at Miller, tradition is clearly king. After all, the brewery still makes its beer using the yeast that Fred Miller carried with him across the ocean in his pocket, sandwiched between two sheets of absorbent paper.

"We do feel a connection (to Milwaukee predecessors)," says Miller’s Dr. Ryder, "and it’s actually very nice. In fact I was thinking yesterday, Fred Miller died in 1888. Supposing he could come back today, just for a couple of hours, and see what we’ve done here … here in Milwaukee. He’d be so proud; his brewery, first of all it’s still there, and second of all, it’s making all these different types of beers which he could never even dream of. The quantity would be amazing to him, and the number of people working at the brewery would be amazing to him, as well. He’d be so proud, it would just blow his mind to come back, and just to see it all."

But, says Ryder, a brewery does not thrive on tradition alone.

"Today’s consumer that wants choice, whether it’s the millennial, gen-Xer’s, whatever; we want to be able to provide that choice, and sometimes you can’t necessarily do that using the older yeast strains that we’ve got. That’s why we have six yeast strains that we use now."

Brewing to scale

Though the equipment varies in size and bells and whistles, the basics of brewing beer are much the same at any level. What Jared Sutliff does in his basement is pretty much identical to what Mike Brenner, Dave Hansen and David Ryder do in their breweries.

They all turn water, grain and yeast into beer, and all following the same steps. Where they differ, of course is in scale.

The main difference between 10th Street Brewery and MillerCoors a few miles away is, says Hansen, capacity.

"We have a pretty flexible brew house and that’s not the case around the system. But while we can do more diverse things, we don’t exactly have the capacity to crank it out if it’s something we want a lot of," says Hansen, as we navigate the stainless steel tanks that crowd together in one room of the Leinie’s brewery.

"Bigger breweries will have four or five different vessels. We have two. Fifteen fermenters is all we have. We empty one every day and we fill one every day. It works, but that’s another reason we can’t put out more beer. We can do one batch at a time. So even though we’re doing two brews today, we have to wait for the first one to completely cool so we can start the next."

The Leinie’s team at 10th Street Brewery believes it’s in an enviable position, and they’re the first to admit that it’s nice to have the resources of a major company and the independence to follow your vision and create a range of interesting beers.

Brenner currently has seven beers on tap and is beginning to work toward bottling beer for sale at local taverns, restaurants and retailers. He says he typically brews a few batches at a time, every few weeks, based on demand.

"I’ve got six fermentation tanks so we can do six (varieties) a time but then I have two giant aging vessels so I can do two more in there and we’ve got enough oak barrels to do another four or five different kinds. We usually brew a batch of one thing, put it in the tank, and then (continue)."

What may come as the biggest surprise is this ... It’s easier to brew 300,000 gallons of beer a day than it is to do five.

"Our job is easier, because we’re actually brewing the beer in a volume, rather than the home brewer who is trying to do it in very small batches," says Miller’s Ryder, "and that’s infinitely more difficult, it really is. Way back when I was doing the malting bit, I was also doing a little bit of home brewing. It’s difficult. When you’re doing it on a larger scale, it becomes easier, because you can easier control temperature, and time, and all those kinds of things. It becomes a little bit easier. The down side of that is if a batch of beer spoils on a large scale, you’ve got to throw it away."

You might think that scaling up while maintaining quality is a challenge, and it is. Ryder says that he, along with about 300 MillerCoors tasters, expend a lot of energy and time tasting beers from the company’s 12 breweries to ensure quality and consistency. Especially for brands like Miller Lite, which are brewed simultaneously at multiple breweries, the team must keep a diligent eye (and taste bud) on consistency. Miller Lite samples from all plants are tasted monthly.

But that’s just a part of it.

"We used to have a guy who was here 30 years, and his only job was studying beer bubbles," says Ryder. "This man became the world’s expert on beer bubbles. We’ve got some beers which have a lot of foam, some beers which have less foam, some beers which have a little bit of foam – that would be the foam signature. This man was able to understand what composes a bubble. The hop components combine with the (malt’s) protein components in the bubble wall; to be able to stabilize the bubble wall, you can get more or less foam that way."

So, in terms of who’s got the tougher job, Ryder says the truth is the opposite of what you might think.

"It’s difficult to brew a decent beer at home because so many things can go wrong," he says. "I take my hat off to the home brewer who really wants to make a decent brew. If they like it, they want to do the same thing again; it’s real difficult to be able to do exactly the same thing again as a home brewer. It’s easier for us to do it because we know how we did it, we’ve got everything documented, we’ve got better control."

The secret handshake

It seems, then, that at every level, the brewmaster has got something to learn. And from who better to gain that knowledge than other brewmasters?

"I learn something new every day," says Ryder. "You don’t ever get to a situation where you know everything. We place a lot of emphasis on having the highest quality products, but when it comes to beer styles, we want to know what other people are doing and why they’re doing it. It’s just so important."

So, a large part of Ryder’s job is keeping tabs on the beer made by MillerCoors, but also on beer made by other brewers large and small. It also involves talking to a lot of brewers working across the entire spectrum.

"We all have an appreciation of each other, so whether it’s a home brewer or whether it’s a craft brewer, microbrewer, or whether it’s us, we want to meet, and we want to talk about beer," says Ryder, a glint of enthusiasm in his eye. "That’s what it’s all about."

Sutliff agrees, though he hedges a bit. He says some are more likely to share than others.

"There are a number of fantastic homebrewers that have a connection to the craft beer scene and help out their craft brewer friends on occasion. Some of the local craft brew pubs – St. Francis Brewery specifically – get a hold of the Beer Barons of Milwaukee homebrew club and offer our members yeast from the brewery for use at home. It is more than enough yeast to ferment and the generosity is much appreciated."

Mike Brenner agrees that there’s a mix of camaraderie and competition in the Brew City brewing scene.

"I think in general, people want to be very collaborative and people are very cool to each other. People are very cool and very open and they’re very supportive. I think it’s not to the level of other cities. Some of it’s me, too. Coming from a non-profit realm where there’s a small pool of money and everybody’s fighting for it, I guess I’m just naturally more competitive."

Results are bigger than beer

Though surely some make beer for the paycheck, most glean the biggest satisfaction from the end product, a tangible result of their hard work.

Despite his success – Ryder is acknowledged as a respected expert in his field on an international level and a local one (last month he won the Milwaukee Press Club’s Milwaukee Made) award – his passion for brewing all these years later is plain to see. He’s animated and excited when discussing every aspect of it.

The same passion can be seen on the other end of the spectrum, too.

"For me, I really enjoy the process of brewing: the smells, creativity, science and art along with the time spent with friends and family during the creation and consumption of the product," says Sutliff.

"For a time, I was really interested in getting my beers entered in competitions and receiving the feedback, but now I am more interested in making something that is delicious, not necessarily crafted to a specific style and sharing it with those I care about."