Breaking down racial barriers: Hopeful Milwaukeeans build a better Brew City

In 2000, Judge Derek Mosley — who was a prosecutor at the time — was house shopping. Originally from Chicago, Mosley was not familiar with Brew City neighborhoods, and he didn’t notice at first that the realtor — who he contacted based on a recommendation — showed him homes exclusively on Milwaukee’s North Side.

Mosley — who serves today as a municipal court judge as well as a mentor to numerous youths and board member for many city organizations — chose to live on the Northwest Side and is extremely satisfied with his diverse neighborhood, but he noted that he wasn’t shown houses on the East Side or Brookfield — places he could have afforded.

Early on, Mosley experienced firsthand what others have only heard or read: Milwaukee is the most segregated city in the country.

Segregation certainly makes the list of Milwaukee’s social justice ailments, along with racial inequality, a reality that Paul Schmitz, who founded the Wisconsin chapter of Public Allies and today works as a consultant and activist, experienced as a teenager.

Schmitz grew up in Glendale and attended Nicolet High School where he jokingly claims to have been in the "pharmaceutical business." He and friends also frequented Klode Beach, where they smoked pot and partied at friends’ houses when their parents were away.

In 1985, drug addiction landed the then-16-year-old Schmitz at the now-defunct De Paul Rehabilitation Center.

"All of a sudden, I was this sheltered, middle class, white kid around every kind of person you can imagine," says Schmitz. "The experience of treatment and the recovery process thrust me into a situation where I became conscious of issues around race, class and discrimination. I had all of these presumptions about things and it was only when I became friends with the people I had these presumptions about that I realized we actually had the same issues and challenges."

Schmitz thought back on all the times police had found him and his friends at the park or a party and they were able to talk their way out of the situation or simply have a call to parents — but never an arrest.

"The experience led me to understand how lucky I was to live where I did. I realized that if I lived just a few miles from where I did, or I had not been white, I would have a record," he says.

If I lived just a few miles from where I did, or I had not been white, I would have a record.

Tweet this

Tweet thisMosley’s and Schmitz’s stories begin to illustrate some of Milwaukee’s most problematic issues around racial relations and the other social justice issues that form around race in Milwaukee: issues of economic inequality, violence, equal access to employment, housing and education.

National Public Radio’s Kenya Downs recently reported on findings from a study at UCLA that found Wisconsin K-12 schools suspend black students at a higher rate than anywhere else in the country and Milwaukee Public School’s suspension rate is twice the national average.

According to the report, Wisconsin also has the highest achievement gap between black and white students in the country, incarcerates the most black men in the country, and is the most segregated.

"Milwaukee is a vibrant city known for its breweries and ethnic festivals and can be a great place to live — unless you’re black," wrote Downs.

Granted, for many people the reality of living in Milwaukee is bleak, and yet the city teems with people dedicated to improving issues of race and toward attaining social justice in the city every single day — including Mosley, Schmitz and many others.

This article profiles 11 individuals who are working to build a better Brew City. These dedicated workers don’t always get the recognition they deserve, but they continue to work toward a better Milwaukee anyway — for themselves, for their families and for residents whom they’ve never met.

"There is a lot that’s wrong in Milwaukee, but we are doing some things right," says Mosley. "It’s not the city’s fault nor is the city going to find the solution — it’s the people living here who will do that."

Angela Walker of Wisconsin Jobs Now

Angela Walker was born in 1974, raised on Milwaukee’s North Side and graduated from Bay View High School. Growing up, she spent a lot of time at the library and learned valuable and compassionate lessons from her family.

"My grandmother always told me to leave things better than the way I found them," says Walker.

Walker’s first experience with activism took place while she was attending the University of North Florida. She joined the protests growing against the 2000 presidential elections. Walker has since worked for peace and justice as an individual and through groups, including Occupy The Hood and the Step By Step Collective.

"The largest movements in history did not start out large. They started small — in someone’s house or a coffee shop. These movements started with someone saying, ‘this is ridiculous,’" she says.

Today, Walker serves as the community campaigns coordinator for Wisconsin Jobs Now, a nonprofit organization committed to fighting income inequality and building stronger communities throughout Wisconsin.

Prior to joining Wisconsin Jobs Now in January, Walker was a bus driver for 14 years.

"Transit should be a non-partisan issue, not a political issue, but unfortunately the issue of transit has been ascribed a racial aspect and socioeconomic status that you don’t find on the coasts," she says.

Walker initially worked as a school and Greyhound bus driver. In 2009, she went to work for the Milwaukee County Transit System where in 2011 she became legislative director of the union representing the transit workers.

"I felt both purpose and joy in my job as a bus driver. The bigger the bus, the happier I am," she says. "There’s a saying down south that you either have diesel in your blood or you don’t and I definitely do."

In 2014, Walker ran for county sheriff as an independent socialist against incumbent David Clarke and received, much to her surprise, 67,000 votes.

"I’m not sure people were voting for me, they were voting against him, but still, the number of votes was a shocker," she says.

Walker also works to strengthen public schools and to restore their prominent role in the community.

"Public schools were the hub of the community and you went there if you needed help with lots of issues — family, nutrition, resume training," she says. "Everyone was welcome there, not just people whose kids attended the school. We need to reinvest in public schools and, if we do, we will see a whole lot less of the ‘bad’ in Milwaukee."

Empowering people — even those who claim they "aren’t political" — is one of Walker’s missions in her work and personal life.

"It’s not the activist who everyone knows who makes all of the change; it’s the everyday person, the person who says ‘Hey, I’m one person and what can I do?’ There are a whole lot of ‘one persons’ out there who together are making a big, big difference and it’s encouraging."

There are a whole lot of ‘one persons’ out there who together are making a big, big difference.

Tweet this

Tweet thisDespite the struggles, Walker envisions a better Milwaukee and sees it as attainable.

"We have a unique opportunity right now to figure out how we want to move forward," says Walker. "We need to move beyond the things that keep us divided, stop pretending there is no income inequality and take this opportunity to do something that hasn’t been done here and rebuild this city, craft something that works for everyone. That’s what keeps me going."

Fidel Verdin of Summer of Peace

Fidel Verdin grew up in Milwaukee and graduated from Riverside High School.

"I grew up in an environment where political and social issues were talked about around the kitchen table," says Verdin.

Today, Verdin, a self-taught artist, teaches at several schools and after-school programs. He is also a journalist and a hip-hop artist who performs under the name Viva Fidel.

Verdin combines his passion for art, music and teaching.

"I use the language and elements of hip-hop in my teaching platform," he says. "Hip-hop helps to create a voice that’s critical in a place like Milwaukee. It is a threatening genre to some people because it talks about issues a lot of people don’t want to talk about. It is designed to keep people uncomfortable and that’s good because we don’t ever want to be comfortable with death and destruction."

We don’t ever want to be comfortable with death and destruction.

Tweet this

Tweet thisThirteen years ago, Verdin co-founded The Summer of Peace with Tanya Byrd. Summer of Peace is a city-wide, one-day youth rally created to promote the positive by recognizing young people doing good things in the city. It’s also a celebration of entertainment, art and community.

"The mayor came to the first Summer of Peace and signed our peace pledge," says Verdin. "There aren’t a lot of initiatives that speak to a solution, so we took it upon ourselves to do this."

What started out as a small gathering has grown into a large-scale collaborative effort with 30 other agencies. A big part of Summer of Peace — as well as Verdin’s personal philosophy — is to change the language in and around the central city.

"We’ve created a change in the conversation. We don’t say, ‘put the guns down, stop the killing, stop the violence.’ Instead, we talk about youth leadership, collaboration and promoting the positive," says Verdin. "Peace is now in the conversation and we are really, really proud of that."

Summer of Peace takes place every August in different county parks including Gordon Park, Kadish Park and Washington Park. Last summer, the group worked with Milwaukee Urban Gardens and created a "peace park" and public gardening space on the corner of 5th and Locust Streets that then served as the event’s home base.

"Because of the work and sweat equity we put in last summer at the 5th Street park, we are now in conversations with the city about a bigger space," says Verdin. "It’s about repurposing and place-making and creating something young people can take ownership of and feel good about."

Reggie Moore of Center For Youth Engagement

Reggie Moore grew up on 12th and Reservoir in Milwaukee. His parents lived in the south and in Chicago before moving to Milwaukee. They divorced when he was 5 years old and Moore and his mother moved to a North Side housing development.

"It was a stable and communal environment, even though it was the projects," says Moore.

Growing up, Moore saw an increase in crack usage and violent episodes in his neighborhood, and his mother — an activist who marched against the death of Ernest Lacy (who died while in Milwaukee police custody) — opened her home to struggling neighbors.

"Our home became a hub for the neighborhood. It wasn’t a formal community center, but it functioned as one," says Moore. "I felt very much a part of my community, and the importance of that was ingrained very early with me."

Moore says he did not encounter racism until middle school, at which time someone called him a racial slur. "I had so much self love and pride it didn’t destroy me," says Moore.

Moore went on to be a part of the YMCA’s Black Achievers Program and then on to graduate from Juneau High School where he was a founding member of a youth-led group that helped young people engage in community service. Moore later got his first job teaching art to kids.

"These little kids valued my skills and I was getting compensated for it," he says. "This was a spark."

Helping kids understand that they can achieve in a variety of fields has become part of Moore’s mission.

Teens can become agents of change instead of objects of it.

Tweet this

Tweet this"Most young men of color see sports and entertainers getting recognition and it makes them think their aspirations are limited because that's what is promoted in our society," says Moore. "They don’t realize engineers, artists and others can get recognition, too."

In 2000, Moore and his wife, Sharlen, founded Urban Underground with a group of teens and young adults. The purpose of Urban Underground is to provide young people with tools and knowledge that can change their individual futures and the future of their community.

"Urban Underground is a place where teens can become agents of change instead of objects of it," says Moore.

In 2011, Moore founded the Center for Youth Engagement, which serves as an intermediary to guide, evaluate and organize dozens of organizations and social service agencies that serve the city’s at-risk youth.

"I wouldn’t say it’s getting worse in Milwaukee, but it’s hard to say it’s getting better," says Moore. "The hardest thing is that people think they understand racial justice and they don’t. Many people want to ignore it altogether. It makes them uncomfortable. But the key is for people to go where they have been afraid to go, because the only reason they are afraid is because they have been misinformed."

Ava Hernández of Public Allies

Ava Hernández has worked with Public Allies Milwaukee for seven years and is currently serving as its Interim Director. According to Hernández, Public Allies Milwaukee’s mission is to advance new leadership to strengthen communities, nonprofits and civic participation.

"Each year, we identify talented young adults from diverse and under-represented backgrounds who have a passion to make a difference, and help them turn that passion into a viable career path in community and public service," says Hernández.

More than 67 percent of the Allies are people of color, 60 percent are women, 50 percent are college graduates and 15 percent are LGBT.

"And 100 percent care about making a positive difference," says Hernández.

Public allies serve in full-time paid positions at local nonprofit organizations where Hernández says they create, improve and expand services with measurable results.

Throughout its 21 years in Milwaukee, Public Allies has supported over 500 of Milwaukee’s diverse emerging leaders and partnered with hundreds of community organizations.

"The work of Public Allies is deeply rooted in social justice and its intersections across a wide array of issues. Our organization moves past traditional forms of leadership that solely value titles and positions," says Hernández.

Hernández says Public Allies is most effective in engaging people and their communities to address race relations.

"We first recognize the problem that racial disparities exist in our city — and nation — across multiple outcomes pertaining to education, health, criminal justice and economic opportunity and see these outcomes as both connected and systemic," says Hernández. "Our allies work to understand these intersections, systems and their responsibility to address disparities in ways that build bridges in an increasingly polarized climate."

Our allies work to understand these intersections, systems and their responsibility to address disparities in ways that build bridges.

Tweet this

Tweet thisHernández moved to Milwaukee from Louisiana almost 10 years ago. At the time, she had little knowledge of the city’s communities or history.

Today, Hernández sees both challenges and beauty in Milwaukee.

"What continues to feed my sense of hope in these difficult times is that this city is filled with people who are courageous in their leadership, who come together despite differences, who demand to be heard in addressing root causes of systemic injustices and who work tirelessly in creative and innovative ways to create change," says Hernández. "I am inspired by the young people in this city who are approaching these critical moments with a sharp sense of clarity, purpose and a demand for a thriving Milwaukee."

Dawn Barnett of Running Rebels

Seventeen years ago, Dawn Barnett was working in restaurant management when she saw a young man near her home wearing a Running Rebels T-shirt and playing basketball "like a pro." She asked her neighbor about Running Rebels and, impressed with what she heard, Barnett attended a volunteer meeting for the organization at the Atkinson Public Library.

"It became very clear to me that young people are born into situations that are heartbreaking and they don’t know a better way until they are shown a better way," says Barnett. "And after they are shown a better way, they deserve a second chance."

Barnett knew that working for this organization was her calling, and she quit her service industry job before she was hired by Running Rebels. However, Barnett went on to eventually become the co-executive officer as well as marry the founder, Victor Barnett.

Victor Barnett started Running Rebels 35 years ago. It began as a small basketball-focused program staffed by volunteers and today employs more than 100 people. His vision is to provide positive choices for youth facing the daily pressures of delinquency, drug abuse, truancy and teen pregnancy. He saw the need for a positive, alternative outlet for central city youth that combines support with demonstrating that someone cares about their needs.

Every single interaction we have is an opportunity to make someone else’s life better.

Tweet this

Tweet thisIn 1996, Running Rebels moved to its current location, 1300 W. Fond du Lac Ave., and liaisons from the program are stationed in six Milwaukee public schools.

Running Rebels after-school offerings focus on improving academics, daily living skills, cultural awareness, anger management, sports, job preparation, music performance, gang prevention and many more. Running Rebels also offers a Severe Chronic Offenders Program, as well as Firearms, First Offenders, First Time Burglary Offender and Violence-Free programs.

"Our intervention helps young people who have been caught up in the system with the ability to stay in the community under strict supervision instead of going to jail," says Barnett. "It provides an opportunity for them to start making better choices."

According to Barnett, the program has an 80 percent success rate.

Barnett says the key to a more compassionate Milwaukee starts with treating all people with courtesy and respect.

"Every single interaction we have is an opportunity to make someone else’s life better. It’s amazing what I found when I became intentional of my interactions, when I gave even just a little bit of attention to someone. The universe opened up," says Barnett.

Ken Hanson of Greater Together

Ken Hanson grew up in Menomonee Falls with a father whom he describes as an "old school democrat" and his mother, a devout Catholic.

"I went to a parochial school and my takeaway was that we are all the same and anything else is wrong," says Hanson.

There were three churches in the community, and Hanson’s mother chose the one that spoke of social justice, particularly the work of activist Father James Groppi. This had an effect on Hanson, who would later go on to become a designer and eventually open his own business, Hanson Dodge, which continues to thrive in Milwaukee’s Third Ward neighborhood.

When the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA), the only professional organization for design, asked Hanson to help program its 100th anniversary celebration, Hanson — who started the AIGA chapter in Wisconsin years ago — agreed.

"I think the expectation was that I would do a show, but I decided I would rather do something else," says Hanson. "I’ve always defined designers as the people who change the course of things, so I started thinking the best way to celebrate the past 100 years was to galvanize people to see themselves as a vital part of the next 100."

Hanson saw a role for designers and marketers in the world of activism and social justice.

"There are a thousand activists working in the central city doing what our tax dollars can’t do anymore, they are the soldiers, the people doing the work," says Hanson. "And we can market their ideas, and by that I mean get their work, their ideas, out there."

Shortly after having this thought, Hanson, while on his way to work, heard on the radio that Milwaukee’s 53206 zip code had the highest incarceration rate in the world.

"I couldn’t believe it. Not Kentucky, not Alabama, but right over there," says Hanson. "It became really clear to me that although Milwaukee has been very good to me, it hasn’t been so great for many people who live here."

Hanson began reaching out to people, including James Hall of the NAACP, Molly Collins of the ACLU and Bob Peterson of Rethinking Schools and started to formulate his idea that later became the Greater Together Coalition.

Led by AIGA Wisconsin and supported by NEWaukee, the coalition encouraged designers to get involved in community problems, specifically race relations.

Last summer, the group announced The Greater Together Challenge, a competition launched to create awareness, hope and ideas to dismantle segregation, as well as address racial and economic inequality in greater Milwaukee.

Approximately 130 ideas were submitted — Hanson says he was hoping for 100 — and 15 finalists were chosen. In October, the finalists presented their concepts at an event at Turner Hall.

It’s good for people to take on shit that’s hard.

Tweet this

Tweet thisNichole Yunk Todd, director of policy and research at Wisconsin Community Services, won the $5,000 prize for her plan to provide free driver’s education classes to each Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) student.

Hanson was sometimes criticized for his efforts, including that running an organization of volunteers, instead of paid staff, excluded poor Milwaukeeans — who often lack "free time" due to demanding, low-paying jobs.

"I’m not suggesting I have a solution. I’m suggesting I have strategies," says Hanson. "I have no credibility. Although I feel fairly accomplished in my profession, I admit I’m an interloper here. It’s good for people to take on shit that’s hard. As we get older we just want to be great at everything, but it stunts your growth. I don’t mind being an amateur sometimes."

Pat A. Robinson, photographer

Pat A. Robinson was born in South Bend, Ind., but moved to Milwaukee and lived in various places in the city until his family settled at 26th and Locust Streets.

Robinson graduated from West Division High School — now the Milwaukee High School of the Arts — where he first studied photography. He then took photography classes at Milwaukee Area Technical College and later went into the Navy where he gained more photography skills.

He works as a freelance, contract photographer for the City of Milwaukee, as well as The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and others. He has chronicled Milwaukee’s African American community since the 1970s.

"I shoot street photography. I’m out in the neighborhoods, just documenting what’s going on," says Robinson. "Spontaneous, on-the-fly kind of stuff, anything from a portrait to a festival. I like to shoot anything where people are involved."

Recently, Robinson participated in a couple of Fresh Perspective Art Shows, events organized by Willie LaMar and Tim John that showcase positive art by local African American males.

"We are all artists that don’t have a lot of money and don’t get a lot of exposure but we have a lot of positive documentation to share," says Robinson. "For some of the men involved art has replaced something negative in their lives and has become a good escape."

Although Robinson enjoys his work as a photojournalist, he understands that the media often portrays only a portion of the central city, which often gives people who are unfamiliar or misinformed with the area a jaded and unrealistic perspective.

"The media usually shows the bad images of the community — I’m guilty of this, too, because I work for the media sometimes — but in my creative work I prefer to photograph the good things that the people do. The volunteer work, not the shootings," says Robinson.

Darius Scott of Urban Underground

Urban Underground’s mission is to provide youth with alternatives to violence, support for academic achievement and increased chances for higher education and employment instead of incarceration.

Today, Urban Underground stands as a nationally recognized model for increasing civic participation and youth-led social change.

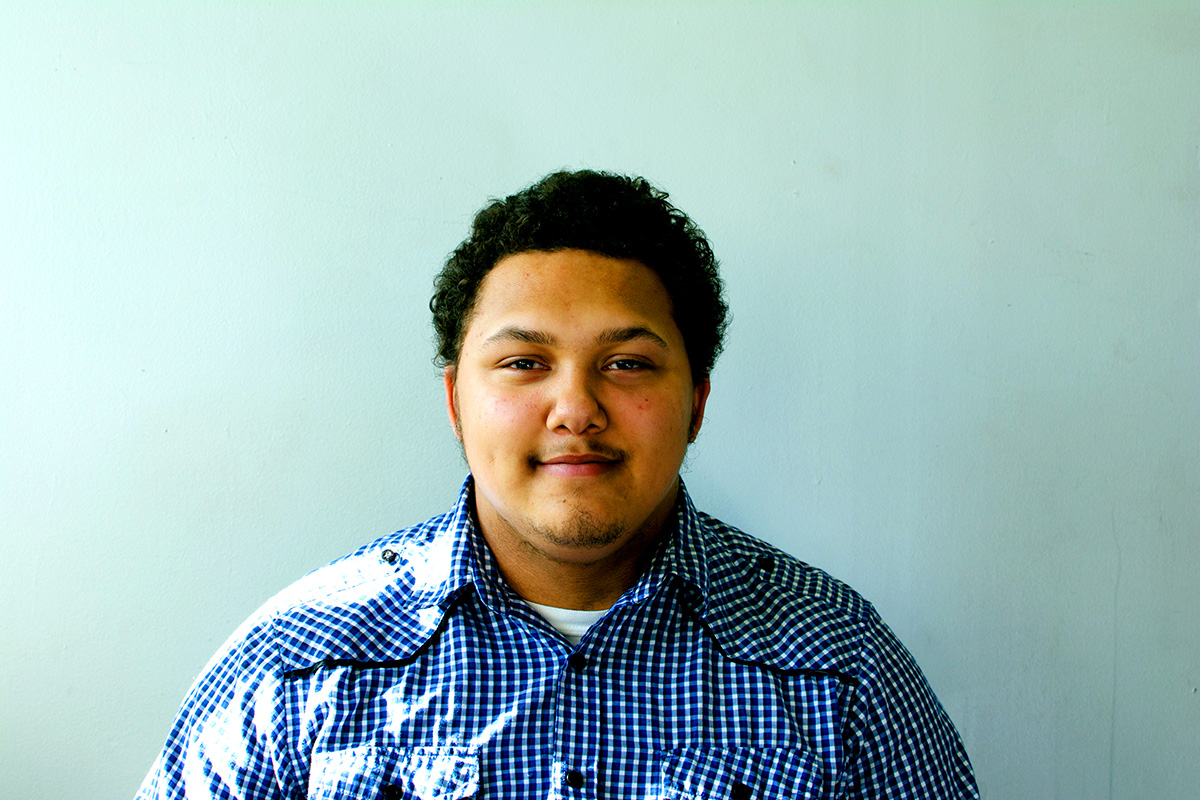

Darius Scott started out as a student at Urban Underground and is now a program coordinator.

"Our goal is to make sustainable leaders," says Scott. "Young people go through the program and while doing so, they come into themselves, feel comfortable about being change advocates in the community and then find a way to do something to make change in the community. Basically, they understand they have control and they can change their community and sustain it."

Every year Urban Underground reaches out to schools and street corners for teens who want to make a change in themselves and the city.

Kids who participate in Urban Underground design and implement projects that focus on the organization’s four core issues of juvenile justice, public safety, health and education. They meet weekly to work on their group projects and are also eligible for individual support with academics, applications and personal issues.

Kennedy Holliman is a junior at Hope Christian School and a member of the Urban Underground.

"Before I came here I didn’t know my opinion mattered or that I mattered," says Holliman. "It opened my eyes that there’s more to life than just myself. I have to help people around me to help myself. I think if somebody my age or younger would know these things growing up, it would change them for the better."

Sarah Dollhausen, Shalina Ali and Tyrone Miller of TRUE Skool

When Sarah Dollhausen found out she was pregnant at 17, she knew she had to make major changes in her life. After her daughter was born, she earned a degree in IT and taught computer classes to young people at a community center.

"I realized the kids didn’t want to sit in another classroom, especially after school or in the summer, and I started to think about how to teach kids in a way that would interest them," says Dollhausen.

In 2004, Dollhausen started TRUE Skool, an organization that uses the urban arts to engage youth in social justice, community service and civic engagement.

TRUE Skool offers an after-school and summer Urban Arts Program along with other services such as workshops, community service projects, commissioned art / mural projects, dance performances and special events.

"We understand how popular culture, specifically hip hop culture, has the power to provide unexplored opportunities for young people," says Dollhausen. "The arts are the carrot that lead them to find out about how they can be more involved in their community."

TRUE Skool, located in the ground floor of The Shops At Grand Avenue Mall, is open to kids ages 14-19. There is no cost, but students are required to commit 10 hours of community service per session.

"This age group is crucial," says Dollhausen. "It’s make it or break it time. You can do some crazy stuff or continue on a path of success. We’re here to help them choose success."

TRUE Skool is not like a typical after-school drop-in program: It requires its students to make a two-to-four year commitment and to attend three days a week after school during the academic year as well as during summer vacation.

Shalina Ali is officially the program director, but known to TRUE Skoolers as "mom." Ali leads, among other classes, an "art of coping" class that asks students to incorporate themes of mental health — from depression to suicide — into their paintings.

"TRUE Skool is about being an artist, but also wanting to be engaged in the community and be part of something larger then yourself," says Ali, who is also a photographer and member of the group Latinas Cameras.

Tyrone Miller is a DJ and music blogger who serves as TRUE Skool’s music director. He teaches youth emcee skills and how to write and record original music.

"If you can get comfortable performing in front of a crowd of 100 people, you can use the same skills in the professional world. Kids learn that these skills are transferable," says Miller.

Milwaukeeans for a Better Brew City

This article can only showcase a cross-section of the many Milwaukeeans who are doing the important work of making our city all it can be, but it is not enough. To attain social and economic justice in Milwaukee — in order for real change to occur — will take the work of everyone.

"We as Milwaukeeans need to get out and get to know each other. It’s the only way to improve the situation," says Derek Mosley. "It’s not easy for some to do this. To go to places outside of their comfort zones or spend time with people who are different from themselves."

Mosley says his group of Facebook friends is a microcosm of Milwaukee segregation.

"Out of 5,000 Facebook friends, 2,000 are black, 2,000 are white and almost all of them have been raised in this city," says Mosley. "And yet, they do not know each other."

Schmitz also believes physically moving beyond invisible barriers is a key to improvement.

"People have such irrational fear of the city and the central city. People live there every day and they are fine, for years, for lifetimes," he says. "Yes, there can be ‘dangerous’ areas, but the way most people who don’t live in the city think about this is not reality, rather what they’ve been fed primarily from local news."

Milwaukee media often tells a story about the worst of a community instead of focusing on the positives and the potential of our city. The people who comprise our city deserve to be seen and treated in their full humanity. This may start with the work of the people profiled in this article, but it ends with each of us.

· · ·