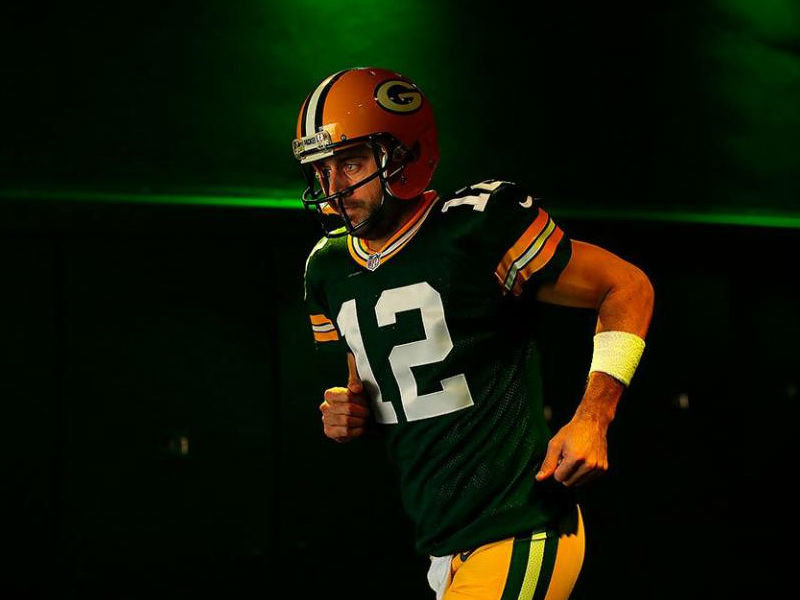

Every week during the NFL season, Aaron Rodgers stands in front of his locker and answers questions from the media about his most recent performance, or the upcoming opponent’s defensive scheme, or the Packers’ invariably mounting injuries. When he is asked something more probing, non-football-related, he doesn’t necessarily shy away or offer a "no comment;" but he generally offers less true candor or consideration than the assembled reporters know is available to the notably cerebral Green Bay quarterback.

That background of Rodgers’ typical restraint, the withholding shrewdness of one of sports’ most talented and interesting figures, is what makes Mina Kimes’ recent profile of him in ESPN – the story will appear in the Sept. 18 issue of ESPN The Magazine but was published Wednesday online – so fascinatingly fantastic.

Rodgers’ insight, honesty, openness and depth is almost startling. Kimes – who notes that he records their conversation, as well, in order to not be taken "out of context" – comprehensively captures his complexity and contradictions: famous but private; fiercely competitive but not some shoulder-chip-hoarding grudge-holder; increasingly spiritual but decreasingly religious; a football savant who is dedicated to the game but is not obsessed with it, who’s excited about his life’s next chapter, but doesn’t know what it will be and is searching for something more.

That’s probably sufficient second-rate reconstitution of Kimes’ great work. Packers fans should definitely read the entire terrific piece. But we’ve excerpted some of Rodgers’ comments from the article, with added context, that are particularly relevant and compelling.

(To read OnMilwaukee's story about Rodgers' journey from tiny teenager to NFL MVP, click here.)

On his thoughts, after Green Bay won Super Bowl XLV, about wanting something else:

Rather, he realized he was still looking for something – for a sense of clarity, or purpose – that was beyond his current line of sight. "It's natural to question some of the things that society defines as success," he says. "When you achieve that and there's not this rung – you know, another rung to climb up in this ladder – it's natural to be like, 'OK, now what?'"

On religion and his changing beliefs:

"I think in people's lives who grew up in some sort of organized religion, there really comes a time when you start to question things more," he says. "It happens for some at an early age; others, you know, maybe a little older. That happened to me six or seven years ago."

"I remember asking a question as a young person about somebody in a remote rainforest," he tells me. "Because the words that I got were: 'If you don't confess your sins, then you're going to hell.' And I said, 'What about the people who don't have a Bible readily accessible?'"

Then, not long after he became the starter in Green Bay in 2008, he met Rob Bell, a young pastor from Michigan whom the Packers invited to speak to the team. When the talk ended, Rodgers waited for the group to dissipate and then introduced himself to Bell, best known for his progressive views on Christianity. The two men struck up a friendship. Bell sent Rodgers books on everything from religion to art theory to quantum physics, and the quarterback gave him feedback on his writing. Over time, as he read more, Rodgers grew increasingly convinced that the beliefs he had internalized growing up were wrong, that spirituality could be far more inclusive and less literal than he had been taught. As an example, he points to Bell's research into the concept of hell. If you close-read the language in the Bible, Rodgers tells me, it's clear that the words are intended to evoke an analogy for man's separation from God. "It wasn't a fiery pit idea – that [concept] was handed down in the 1700s by the Puritans and influenced Western culture," he says.

"The Bible opens with a poem," he adds. "It's a beautiful piece of work, but it was never meant to be interpreted as I think some churches do." I ask him whether he still sees himself as a Christian, and he says he no longer identifies with any affiliation.

After Super Bowl XLV, Rodgers and Bell spent a lot of time talking about what he experienced on that bus -- how he felt, or didn't feel, and his realization that absolute success on the field didn't make him completely content. It wasn't until he confronted his own "narrow-minded" views about the world and his place in it, he says, that he experienced a sense of the fulfillment he yearned for. "I think questions like that in your mind lead to really beautiful periods where you start to grow as a person," he says. "I think organized religion can have a mind-debilitating effect, because there is an exclusivity that can shut you out from being open to the world, to people, and energy, and love and acceptance.

"That wasn't really the way that I was, maybe the first 25 or 26 years of my life," Rodgers continues. "I was, you know, more black-and-white. This is what I believe in. And then at some point ... you realize, I don't really know the answers to these questions."

On living in Los Angeles and how he feels about fame:

He's wary of complaining about his own celebrity, given the attendant benefits. But he admits there are "some things" that cause him discomfort. "Decreased privacy," he says. "And increased strain or pressure or stress associated with relationships. Friendships and dating relationships."

On his high-profile relationship with actress Olivia Munn and the couple’s breakup in April:

I ask him what he learned from the experience. "When you are living out a relationship in the public eye, it's definitely ... it's difficult," he says, jostling on the sofa and blinking a little, as though I've just pointed a flashlight at his face. "It has some extra constraints, because you have other opinions about your relationship, how it affects your work and, you know, just some inappropriate connections." It seems clear that he's referring to the fans and pundits who asked whether his famous girlfriend might be hurting his performance, so I say as much. He nods, adding, "They're such misogynists, right?"

On his family, and why he never responded to comments from younger brother Jordan that they have a fractured relationship:

"Because a lot of people have family issues," he says. "I'm not the only one that does." He tells me he doesn't see any upside in discussing those issues in public. "It needs to be handled the right way."

It bears mentioning that Rodgers never pulled me aside to tell me off the record his side of the story (about this or any critique). His belief in the value of privacy is abiding. "I think there should be a separation between your public life and your personal life," he says. "I've just always felt like there should be a time when you don't have to be on."

And yet, in recent months, he's tried to open up a bit more. "I do have a desire to be myself and not have to feel like I've got to be so private," he says. "I think, because I live in a fishbowl, you either kind of internalize everything or you just relax and let life be." He mentions a couple of times that he recently joined Instagram.

On his political involvement and beliefs:

Rodgers moved to Green Bay when he was 21. Since then, he has voted in every major election: presidential, local, even the 2012 failed vote to recall Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker. When I tell him I was surprised by his level of civic participation, he shrugs it off. "I'm a proud Wisconsin resident, so I feel like it's a duty of mine to vote in the Wisconsin elections," he says.

Rodgers tells me that he doesn't identify with any political party but that he believes some issues shouldn't be partisan: climate change, human rights, civil liberties. I ask him if he's wary of possibly having to decide whether to visit the Donald Trump-helmed White House (this year, several Patriots made news when they skipped the NFL champions ceremony) and he grins. "No, because that means we're in the Super Bowl." He adds: "I don't shy away from those things. I think that you just have to think about what you say before you say it. But at the right time, you can say things that have a major impact."

On envying the NBA’s culture, in which athletes are more openly outspoken on social issues, and why the NFL isn’t like that:

"The guys who are most vocal in the NBA are the best players," he says. When I point out that he obviously falls into that category for the NFL, he says he believes that he can say what he wants but that it has to feel "authentic." He mentions that he's interested in taking on a role in the players' union (he used to be a players' rep), leveraging his unique position to strengthen their cause.

I ask him why he thinks the NFL is more restrictive than the NBA, and he points to the structural differences between the sports: specifically, the absence of guaranteed contracts in football. "[In the NFL], if you're on the street, you're not getting paid unless you have some sort of bonus that goes into another year. So there's less incentive to keep a guy, which gives you less job security. Less job security means you've got to play the game within the game a little tighter to the vest," he says. "Part of it has a really great nature to it – being a good teammate, being a professional – the other part is not being a distraction. And I use 'distraction' as more of a league term."

We talk about his friend and former Cal teammate, recently retired Patriots and Chiefs lineman Ryan O'Callaghan, who came out as gay in June. In an interview on OutSports.com, O'Callaghan described how he feared coming out, even contemplating suicide for years. "I'm incredibly proud of him," Rodgers says. "I know he had a lot of fear about it, and how he would be accepted, and how people would change around him. I think society is finally moving in the right direction, as far as treating all people with respect and love and acceptance and appreciation. And the locker room, I think the sport is getting closer."

He adds that players like O'Callaghan worry about retribution not only from their teammates but also from executives, again pointing to the absence of guaranteed contracts. "There's a fear of job security," he says. "If you have a differing opinion, differing sexual orientation, they can get rid of you. So is it better just to be quiet and not ever say anything? And not risk getting cut, with people saying: 'Well, it's because you can't play'?"

On currently unsigned quarterback Colin Kaepernick and protesting the national anthem:

I ask Rodgers what he thinks, and he demurs at first, then says it would be "ignorant" to suggest Kaepernick's stance didn't play a role in his employment status.

A few weeks later, he reaffirms his point. "I think he should be on a roster right now," he says. "I think because of his protests, he's not."

Rodgers tells me that while he doesn't plan on sitting out the anthem, he believes the protests – which he describes as peaceful and respectful – are positive, mentioning that he's had conversations with a new teammate, tight end Martellus Bennett, about the issues they represent. "I'm gonna stand because that's the way I feel about the flag -- but I'm also 100 percent supportive of my teammates or any fellow players who are choosing not to," he says. "They have a battle for racial equality. That's what they're trying to get a conversation started around."

I ask him what he thinks about that battle – the actual subject of Kaepernick's protest. As always, he pauses to collect his thoughts. "I think the best way I can say this is: I don't understand what it's like to be in that situation. What it is to be pulled over, or profiled, or any number of issues that have happened, that Colin was referencing – or any of my teammates have talked to me about." He adds that he believes it's an area the country needs to "remedy and improve" and one he's striving to better understand. "But I know it's a real thing my black teammates have to deal with."

When Rodgers explains how his worldview has evolved over the past six years, he says he has grown better at seeking out people with backgrounds different from his. He doesn't offer many examples, but Packers receiver Randall Cobb, one of Rodgers' best friends in Green Bay (he was recently a groomsman in Cobb's wedding), describes the quarterback as a "sponge" in all matters, including social issues. "As we've grown closer, I've been able to give him the perspective of a black man who grew up in the South and opened his eyes to the challenges in my life," Cobb says. He adds: "Football is one of the things we rarely talk about when we're outside the building."

On being notoriously competitive:

"I've always wanted to be the best and hated losing, I think, more than I enjoyed winning," he says. He does object, however, to the stories that paint him not just as competitive but also as incapable of letting slights fall to the wayside. "I'm not the grudge holder I'm accused of being," he says. "I don't have this stack of chips that I, you know, need to have on my shoulder all the time."

Unprompted, Rodgers mentions a 60 Minutes story from 2012 that focused on his responses to perceived slights, a piece he says left him frustrated and confused. "So then that narrative kind of gets out there a little bit," he says.

I point out that when he criticizes a show like 60 Minutes for making him look sensitive, it makes him look, well ...

"Yeah." He smiles. It's true, he admits, that he used to dwell on the indignities he faced in his youth – that he kept the rejection letters from Division I colleges, called out analysts who misjudged him, needled his coach, Mike McCarthy, about passing on him in the draft (McCarthy was San Francisco's offensive coordinator in 2005). It's all true! And yet: "I just don't need it the same way I used to need it," he says. "That was what fueled me – to wake up at 5 o'clock and work out before school and stay after and do extra sets and do extra throwing. The root of that was to be great ... to prove a point every single day. I don't need to prove a point every single day anymore."

On his "run the table" line last year that helped turn around the Packers' season:

Entering his 13th season, Rodgers must find new sources of motivation, catalysts that, more often than not, come from within. Take Run the Table. In November, the Packers were 4-6, and it seemed like they'd miss the playoffs for the first time in eight years. On a Wednesday, Rodgers looked at the standings and realized the team would probably have to win out in order to make it to the postseason. So he stood in front of a gaggle of reporters and, in a moment that has since been memorialized in countless montages, said: "I feel like we can run the table, I really do." And they did.

Rodgers says he wasn't anxious about his prediction. "I wanted that extra pressure on myself," he says. "If anybody had any nerves or stress or pressure or doubt, just, you know, put it on me. I'm going to play better. And then, in turn, if everybody else is less stressed and feels less pressure, they're probably going to play better too." Over the course of those six games, he threw 15 touchdown passes and zero interceptions. It was arguably the most impressive stretch of his career, and the Packers made it to the playoffs, where they lost, somewhat brutally, to the Falcons in the NFC championship game.

On non-football interests and whether he’d be upset if he only won one Super Bowl in his career:

For once, he answers quickly: "No." He adds: "I mean, it'd be disappointing. But no. I'd love to go back at least a few more times. But at some point, my career's going to be over, and I'm going to move on and do other things and be excited about that chapter in my life."

At the moment, that next chapter is a work in progress. While Rodgers has a number of business interests – he says he'd prefer not to name them because he wants them to stand on their own – he's also spent the past few years exploring fields that were foreign to him, picking the brains of experts like film producers, investors and CEOs. He loves – like really, really loves – documentaries. One of his other passions is health care. After watching a former coach battle cancer, he grew interested in his treatment and wants to explore new forms of therapy for the seriously ill, including better nutrition. As we discuss his various enthusiasms, it dawns on me that he hasn't brought up football, so I ask him whether he'll be done with sports when he retires. "Sports will always be a part of my life, but I don't have a desire to coach them or broadcast," he says.

Throughout our conversation, Rodgers mentions several times that he cherishes his work on the field. He has no plans to leave the game any time soon. But the time he's spent searching for meaning outside football has, paradoxically, made him cherish it more, he says. "Because I'm not obsessing over a ball."

On finding true happiness:

It had been six years since Rodgers' trip to the Super Bowl, and Bell still remembers what his friend told him after he won: "'I've been to the bottom and been to the top, and peace will come from somewhere else.'"

Again, read the full ESPN profile of Rodgers here.

Born in Milwaukee but a product of Shorewood High School (go ‘Hounds!) and Northwestern University (go ‘Cats!), Jimmy never knew the schoolboy bliss of cheering for a winning football, basketball or baseball team. So he ditched being a fan in order to cover sports professionally - occasionally objectively, always passionately. He's lived in Chicago, New York and Dallas, but now resides again in his beloved Brew City and is an ardent attacker of the notorious Milwaukee Inferiority Complex.

After interning at print publications like Birds and Blooms (official motto: "America's #1 backyard birding and gardening magazine!"), Sports Illustrated (unofficial motto: "Subscribe and save up to 90% off the cover price!") and The Dallas Morning News (a newspaper!), Jimmy worked for web outlets like CBSSports.com, where he was a Packers beat reporter, and FOX Sports Wisconsin, where he managed digital content. He's a proponent and frequent user of em dashes, parenthetical asides, descriptive appositives and, really, anything that makes his sentences longer and more needlessly complex.

Jimmy appreciates references to late '90s Brewers and Bucks players and is the curator of the unofficial John Jaha Hall of Fame. He also enjoys running, biking and soccer, but isn't too annoying about them. He writes about sports - both mainstream and unconventional - and non-sports, including history, music, food, art and even golf (just kidding!), and welcomes reader suggestions for off-the-beaten-path story ideas.