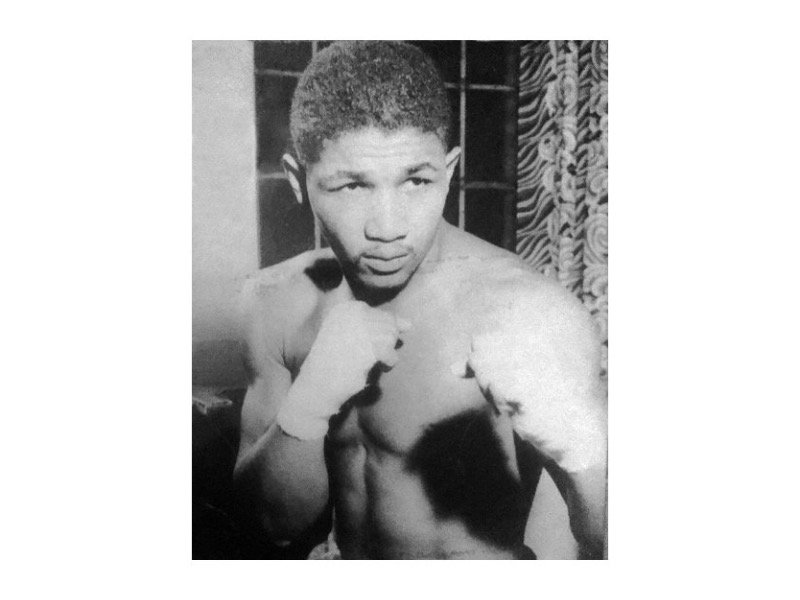

In 1966, West Allis native Don Lutz was a professional boxer in Miami Beach, Fla. The former Golden Gloves champion had worked his way there with the Royal American Carnival to join the boxing stable of trainer-manager Angelo Dundee at the famous 5th Street Gym, where Lutz trained with numerous world champions, including Muhammad Ali.

"I believe (Ali’s) true greatness is in his speed and his originality," wrote Lutz in a letter at the time to the Wisconsin Correspondent for The Ring magazine – me. "You have to watch the guy every day in the gym to really appreciate him. He does so many original things it is almost unbelievable."

Lutz did roadwork with Ali – "He could run faster backward than I could forward," he noted – and spent a lot of time at the Miami house where the heavyweight champion then lived.

"He teased me a lot," said Lutz, whom Ali called "Whitey," "but he was fun and always nice to me. I did the dishes and was a go-fer, but I was with Muhammad Ali."

The Vietnam War intervened in the boxing careers of both Lutz and Ali in 1966 when both were drafted into the U.S. Army. The 21-year-old Lutz was 18-2-2 in the ring, with designs on the middleweight championship of the world. He was also a part-time college student and could’ve filed for an automatic deferment. But he didn’t, because "I got to live in this country, and some of the things I got to do were grand and great, like go to school and live where I wanted.

"So I decided," he said, "that if they wanted two years of my life, they got it."

Lutz went to Vietnam as a medic, was wounded twice and survived three helicopter crashes as well as a direct hit by an enemy shell on the bunker in which he was sleeping.

He came home after 18 months with two Purple Hearts and the Bronze Star, but the horrors Lutz saw and endured in Vietnam effectively ended his boxing career.

"I didn’t have a killer instinct anymore," he said.

Claiming conscientious objector status, Ali refused to go into the Army, was convicted in 1967 of evading the draft (overturned in ’71), was stripped of his heavyweight title and didn’t fight again for three years.

Lutz had no problem with Ali’s decision, because in America everyone has the right to choose his own path.

"I’m not a ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’ or ‘America: Right-or-Wrong’ guy," he said. "I did what I thought was right. I made my choice and I’ll stand by it."

When Lutz spent months recovering from his wounds at a Veterans Administration hospital in Miami, Ali visited him there. Later, when Ali brought his infant children to the 5th Street Gym, Lutz was the only one allowed to hold them.

"I knew how to hold babies so they didn’t cry," said Lutz, who learned that skill cradling babies in orphanages in Vietnam.

"It was a nice getaway," he said. "We did it because we had to, or that war would have eaten you up."

When Ali went to Manila in The Philippines for his epic third bout with Joe Frazier in 1975, Lutz went along as a member of his entourage.

"Especially after Vietnam, he was very considerate of me," said Lutz.

In 1996, both Lutz and Ali carried the Olympic Torch. Lutz, then an employee of the Milwaukee County Parks Department, was chosen as a "Community Hero Torchbearer" to carry it on a leg of its journey through the city to the Olympic Games in Atlanta. There, of course, the sight of the trembling Ali lighting the Olympic cauldron with the torch riveted the world.

Now a resident of Boynton Beach, Fla., where he lives with his daughter Melissa, the 70-year-old Lutz was interviewed by a local TV station after Ali passed away last week and recalled a remarkable Ali feat that somehow has escaped mention in the lavish media accounts of the late champion’s dazzling achievements: "He could jump into the air and put both legs into his pants at the same time."

Lutz couldn’t do that, but in another long ago letter, he recounted the time he finished a sparring session at the 5th Street Gym and Dundee told him, "You and Ali have something in common."

"Well, I puffed out my chest," wrote Lutz, "and said, ‘Oh, yeah? What?’ Then Angelo said in that wise and true way he had, ‘Yeah – you both don’t like to get hit.’ He said later he meant it as a compliment, but I’m not sure."