CHICAGO – Cyber Monday be damned, there are, thankfully, still a few historic American downtown department stores that, especially during the holiday season, transport us back to an era when such shops ruled retail in American cities big and small.

One of them is the State Street Macy’s in Chicago’s Loop, whose roots go so deep here that more than a dozen years after the buyout that led to its rebranding, the bronze signs out front still say Marshall Field.

The 73-acre store – with 300,000 square meters on multiple stories in a complex of buildings that fills an entire square block at 111 N. State St. – was the world’s largest when it was built and is now third-biggest.

It's so sprawling that the locations of specific departments inside (handbags, cosmetics, etc.) are noted on Google Maps.

Although the shop is always bright and lively and full of unique and record-breaking treasures like the world’s largest Tiffany glass domed ceiling, Macy’s really comes alive as Christmas approaches.

The animated windows and heralding trumpets along State Street, the dangling garlands and lights and decorations inside, and the legendary Walnut Room tree carry on a long-lived tradition.

"It's been (that way) for generations," says Melanie Kersey, Macy’s tourism marketing associate and lead tour guide. "People love to talk about their own personal experiences growing up here. (They) came with their parents and grandparents. Children would get dressed up with their hat and their shoes and their white gloves and their best dresses."

A little history

Born on a Conway, Massachusetts farm in 1834, Marshall Field gained his first experience in retail at the age of 17 working in a nearby dry goods store. When he was 21, Field went west to a brother living in Chicago.

There, he found work in another store and was quickly promoted. In 1865, he and Levi Leiter became senior partners at Potter Palmer’s dry goods company on Lake Street, and it was renamed Field, Palmer, Leiter & Co.

Two years later, Field and Leiter bought out Palmer, and, that year, the company had revenues of $12 million, an astonishing amount for the time.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of Chicagology)

In 1868, Field, Leiter and Co. moved into a building owned by Palmer on State and Washington and remained until the 1871 Chicago fire destroyed the building. Two years later, they moved into the new six-story Singer Sewing Machine Co. building (pictured above) on the same block, but again fire sent them fleeing in 1877.

A new Singer building (at first less ornate, but once a mansard roof was added, the new one looked much like its predecessor) was erected on the same site and Field bought it and moved in. (You can see a good overview of these machinations, including photos of each phase here.)

In 1892, the nine-story first phase of the current building was erected to the east as an annex to the Singer building store, and that structure is the earliest part of the store today. Further growth was stymied by the financial panic of the 1890s.

Field had tapped architect Daniel H. Burnham – along with his firm’s Charles B. Atwood (who worked on buildings at the 1893 fair, including the one that now houses the Museum of Science and Industry) – to draw the 1892 annex.

The retailer hired Burnham again in 1900 to design a new $1.75 million Classical Revival-inspired building to the north of his current store as far as Randoph Street. It opened in 1902.

The retailer hired Burnham again in 1900 to design a new $1.75 million Classical Revival-inspired building to the north of his current store as far as Randoph Street. It opened in 1902.

Two years later another addition connected the annex to the new building, and in 1906, just before his death, Field decided to demolish the Singer building and replace it with another addition, completed in 1907. A final phase in 1914 finally filled the entire square block footprint as seen today.

All of these additions were based on Burnham’s original 1900 design.

The Walnut Room, Tiffany ceiling and more

As part of the 1907 construction, the gorgeous Walnut Room was added, replacing an elegant fourth-floor tea room that opened in 1890 against the better judgement of Marshall Field, who didn’t initially believe he was in the restaurant business, nor did he think he wanted to be.

He was, however, convinced to try by his manager, Ripon, Wisconsin-born Harry Selfridge – who later moved to London and was dubbed the "Earl of Oxford Street" for his retail prowess, a life which was detailed in the recent television drama, "Mr. Selfridge" – and a millinery saleswoman named Mrs. Hering.

"Mrs. Hering developed a clientele because of the intense weather changes (in Chicago)," says Kersey. "Every time the season changed, ladies of Chicago were going for a new hat or two or three.

"One day she's entertaining a client and the woman is losing energy like crazy. And, Mrs. Hering is so intuitive, and with the ‘give the lady what she wants’ (philosophy) instilled in her, pulls out her own lunch: a chicken pot pie that she made from her grandmother's recipe."

The woman was refreshed and enamored of the pot pie. So, she offered a suggestion.

"She says to Mrs. Hering, 'I'm enjoying this so much, I want to make you a deal. If you'll make more chicken pot pies, bring them tomorrow. I'd like to invite my friends to come and then you can show them your latest fashions and we won't have to go back home. We can just make a whole day of it'."

According to legend, Hering agreed, somehow made the pies that night and set up a private dining and showroom area in a back room the next day.

"So she's finding tables, pushing them together," says Kersey. "I think she brought her own white linen from home and maybe silver serving pieces, but she had to transform that into a place to entertain these ladies. It was a great opportunity for her.

"Field was making his daily rounds and heard the laughter coming out of the back room and he opens the door and then, much to his surprise, sees this before him."

And, voila!, Field’s enters the restaurant business, opening a tea room, followed by others, too.

The Walnut Room space – originally called the South Grill Room – was the largest and most popular of a number of restaurants on the seventh floor. Later renamed for its distinctive and regal Circassian walnut wood paneling, the restaurant immediately it became a showplace at the holidays, getting its first tree in 1907.

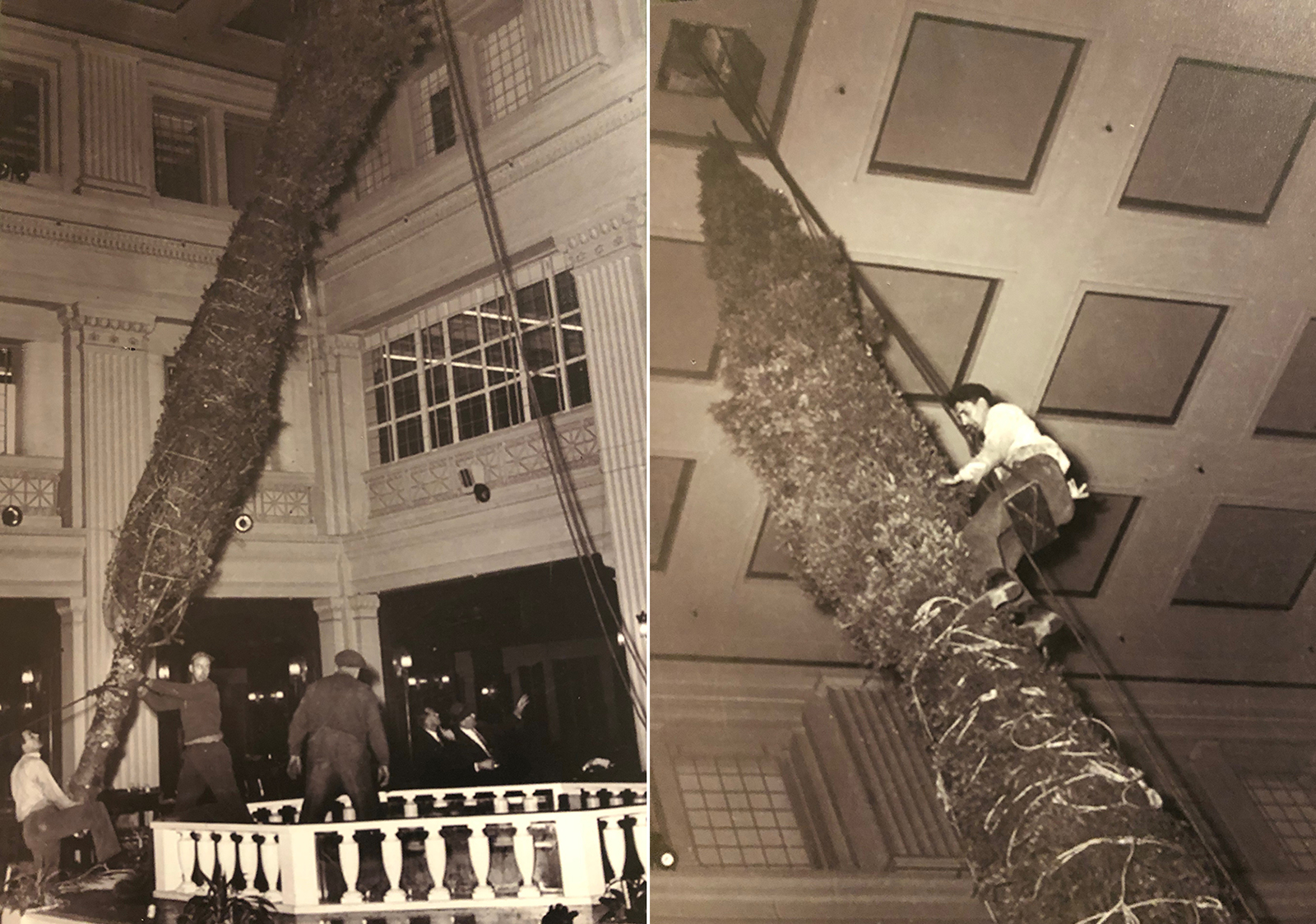

"For over five decades the Great Tree was a 45-foot real tree, hauled up the light well in the store, monitored by firefighters, and gloriously decorated by Field’s design staff," wrote Wendy Bright on her Wendy City Chicago blog. "In the early 1960s, the store made the switch to an artificial tree."

Now, despite the fact that the space isn’t quite as soaring as it once was – the top two floors of the atrium were closed off to create storage in the 1960s, according to Bright – eating a Mrs. Hering pot pie while basking in the glow of the Walnut Room's tree remains a beloved Chicago tradition.

However, now that the upper floors of the building have been sold to Brookfield Asset Management for office space, there’s no longer public access to the eighth floor for the once popular elevated view of the tree.

If you visit, be sure to look above the tree, where you can see the cable that suspends it from the ceiling. That way the weight of the tree does not rest on the floor of the Walnut Room, which sits just above the Tiffany ceiling below.

That ceiling is another feature of the 1907 addition.

Louis Comfort Tiffany had come to Chicago for the 1893 Columbian Exposition and landed a number of commissions, Kersey says.

Tiffany later returned for this job, which kept him in the Windy City for two years, leading a team of 50 artisans, "most of whom were women," says Kersey, "because of the dexterity of the fingers (required)."

The result is stunning from both five stories below, where you can gaze up at it through the bright atrium, or on the fifth floor, where you can see the individual tiles and marvel close-up at the craftsmanship and beauty.

Tiffany used 1.6 million pieces of iridescent glass to cover 6,000 square feet.

While you’re upstairs you can stop and see the old Frango mints demonstration kitchen on the seventh floor, which is currently obscured behind frosted glass, though enlarged vintage photographs on the walls (and camera-wielding visitors with long arms, see below) offer glimpses.

The mints – which became a Field’s favorite after the company acquired Seattle’s Frederick and Nelson department store in 1929 – are no longer made in this building.

Instead, they're made by Gertrude Hawk Chocolates in Scranton, Pennsylvania. But they remain a Macy’s favorite and are still branded with the Field’s name. And, of course, they appear in displays throughout the building.

Outside, through the main entrance on State Street, flanked by 50-foot solid granite columns, we find the two great clocks on opposite corners. The first went up on Randolph Street in 1897 and quickly became so popular that a second, of a different design by Pierce Anderson, followed in 1902.

Five years later, the 1897 clock was replaced with one matching the 1902 design.

Over the years the clocks have served as meeting points, icons of Chicago and even fodder for a beloved and celebrated 1945 Norman Rockwell painting that was later donated to the store. (Later, it was given to the Chicago History Museum).

Today, the clocks' design appears on buttons and on a neon sign just inside the Wabash Street entrance near Randolph.

A fountain had been planned for the 1900 expansion in hopes that it would serve as an interior meeting spot, but Field nixed the idea.

"As the centennial of the store was approaching in 1992 an architectural research firm found those plans and it was decided to build it," says Kersey. "What a great way to mark the centennial."

Next time you're in the store, take some time to snoop around and you'll find some interesting less famous sights, like the seventh-floor Narcissus Fountain Room (pictured above) – a former tea room that now serves an event space – with a big fountain and some vintage tile work (and World War I and II war memorial plaques just outside), and the archive room, which is lined with historical photos of Marshall Field's and the State Street building.

Recently, a portion of the wood paneling (pictured above) from the old board room was installed here, too.

This paneling is without a doubt the oldest feature of the building, having been created in 1603 for the Great House, in Whitehall, Shrewsbury, England, and purchased for the store's interior decorating gallery in 1929. It was moved into a former board room in 1983.

Note, too, the Art Deco metalwork elements – as well as the Field family symbol: a bundle of wheat – scattered around the building.

The holiday windows

Back outside, we stop to admire the holiday-themed windows, the star of which this year is Sunny the Snowpal.

Growing up in New York City, my mother would take me to see the decorations and, especially, the stunning department store holiday windows in midtown Manhattan at Christmas and now I like to take my kids to see the State Street windows at Macy’s each year.

The Sunny windows, created by Roya Sullivan, were unveiled last year at Macy’s in Herald Square in New York and this year debuted in Chicago.

Thanks to advances in glass production, department stores began to decorate their now much-larger windows around 1910, according to Smithsonian Magazine, and these alluring new means of drawing in shoppers quickly proved popular.

"Marshall Field’s inventive window designer, Arthur Fraser, used the big corner window at Washington Boulevard to showcase holiday gift merchandise," wrote Leslie Goddard in the magazine.

"His first panel featured animated carousels and gift-ready toy trains. But in 1944 the store’s new stylist, John Moss, ditched the hard sell in favor of narrative windows – recreating Clement Moore’s ‘A Visit from St. Nicholas.’ The story panels were such a hit they were repeated the next year. ... Not to be outdone, (in 1946) one of Moss’s co-designers, Joanna Osborn, conjured Uncle Mistletoe, a plump, Dickens-like figure decked out in a red great-coat and black top hat. With white wings, he flew around the world, teaching children the importance of kindness at Christmas."

Uncle Mistletoe got a wife, Aunt Holly, in 1948, and the immediately beloved holiday couple was soon immortalized in dolls, puppets and books, as well as on ornaments, napkins, glassware and more.

"At their peak, planning and designing the annual displays began more than a year in advance, with an eager public waiting every November for the reveal of each new theme," wrote Goddard.

"Tens of thousands of fans made pilgrimages from Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota to crowd around the earnest State Street displays in childlike awe."

It’s much the same today, as passersby stop to gather around the windows at all hours of the day. But as night begins to fall and the holiday magic unfolds along State Street – especially if there’s snow – you'll immediately feel what makes Macy's an essential Midwest holiday season stop ... and the stuff of which memories are made.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.