A U.S. Magistrate judge’s stunning decision overturning the Brendan Dassey conviction got me thinking: Maybe we will see a Lawrencia Bembenek outcome here – although if prosecutors release Dassey outright, it would be in the interest of justice. Retrying Dassey is not in the interest of justice.

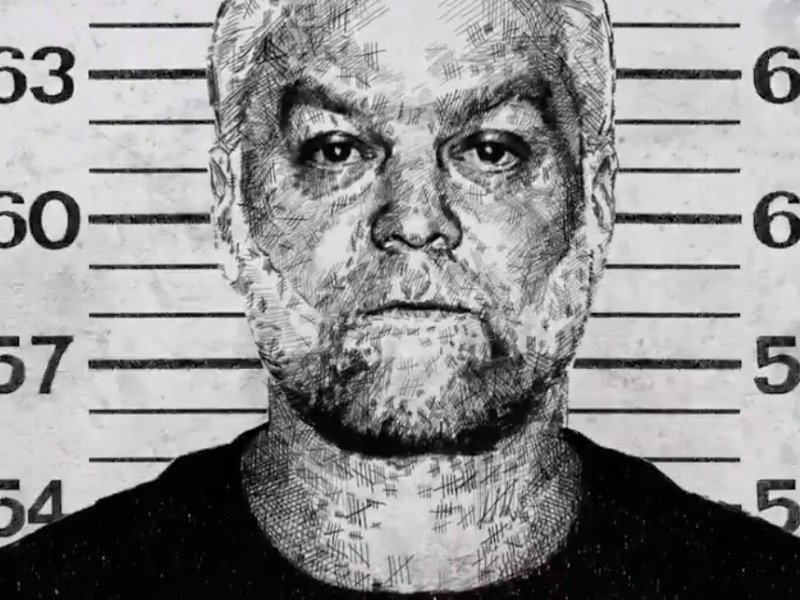

However, the case of Dassey’s uncle, Steven Avery, is very different, and it’s important not to conflate them. In a way, the cases are polar opposites: Dassey was convicted on the basis of confession and no forensics (see a transcript here), while Avery was convicted on the basis of forensics (in part) and no confession. Perhaps ironically, Dassey’s case, with its scant forensic evidence, bears more in common with Avery’s 1985 overturned wrongful conviction than Avery’s conviction in the Halbach murder.

Bembenek, a former Milwaukee police officer, was convicted in 1982 of killing Christine Schultz, her husband’s ex-wife. I am sure you remember the notorious case, but if you don’t, she became a cause celebre when she escaped from prison to Canada. She was captured, but prosecutors then engineered a deal that freed her. She entered a no contest plea, they reduced the charge and they agreed to release her from prison on "time served" years after the conviction. There were simply too many problems with the case. Wrote The New York Times at the time Bembenek died, "In December 1992 a judge reduced Ms. Bembenek’s life sentence to 20 years after she struck a deal with prosecutors in which she pleaded no contest to second-degree murder. She was immediately released for time served."

Dassey, now 26, was convicted in 2007 and received a life prison term with parole eligibility in 41 years. Even if he was involved in the murder of photographer Teresa Halbach as active participant or observer (a huge if at this point), it’s hard not to see his much older uncle, Steven Avery, as the truly malevolent actor, the guy in control. Avery was tried separately and convicted; the magistrate’s decision does not involve his case.

Perhaps we should indeed see a Bembenek outcome here, in which a deal is cut (perhaps for something other than murder) and Dassey is released on time served. I am not sure the defense would accept such an offer as they are in the driver’s seat right now and buoyed by international outrage. And why should Dassey plead out to anything if it’s something he didn’t do? That’s why outright release also makes sense.

However, who knows what happens on appeal if prosecutors appeal? If prosecutors appeal the decision by Magistrate William Duffin (a former business attorney with Godfrey & Kahn) and win, the conviction stands and Dassey stays in prison.

It’s worth noting that Wisconsin appellate courts upheld Dassey’s conviction, so it’s no sure thing that prosecutors would lose on appeal. However, of course, Wisconsin courts also upheld the previous sexual assault conviction against Avery, and everyone knows now that he didn’t do that (and they upheld Bembenek’s conviction too).

The two cases (Bembenek and Dassey) remind me of each other somewhat because it’s always been troubling whether either one of them did it, which didn’t seem to move the courts until the national entertainment media got involved.

"I personally hope that Dassey gets a new trial; his case is currently in federal court and he's seeking one … I am far from convinced that Dassey had anything to do with this and am less convinced even more so that what actually happened matched his ‘confessed’ version of events.

"If Teresa Halbach was brutally murdered in the Avery residence, as Dassey stated, why didn't they find a single speck of her blood in his bedroom? And so forth. The forensic evidence – or really lack thereof – actually conflicts with the Dassey confession in key ways. They didn't find Dassey's DNA or prints anywhere...

"Dassey deserved counsel in the room. And the actions of the defense private investigator are beyond troubling. In the interest of justice, I think Dassey deserves a do-over. He came across like an easily manipulated low IQ youth who kept telling different people what he thought they wanted to hear."

The Duffin decision was stunning in the sense that such appeals in federal court rarely prevail; it wasn’t that stunning for anyone who actually reviewed the evidence (versus just seeing pieces of it presented on "Making a Murderer," which featured Dassey’s case as well as Avery’s).

I read the court transcripts in both cases (and wrote a book summarizing the evidence with OnMilwaukee), and the Dassey case was always far more troubling than Avery’s conviction. It’s hard to see how prosecutors could retry Dassey without his confession, a confession Duffin has ruled involuntary.

The Dassey case was always deeply troubling because there was no forensic evidence tying Dassey to the murder, because of his young age and obvious cognitive problems, and because the "confessions" he gave were so contradictory. What did Dassey see (if anything) versus what he did? Very foggy. Not to mention that the horrific details he gave were not backed up by forensics (he said Halbach was brutally murdered in Avery’s bedroom, for example, but investigators did not find her blood there. And so forth).

The prosecution has really only one move here other than a Bembenek type deal: Prosecutors can appeal Magistrate Judge Duffin’s decision in federal court. Duffin ordered that Dassey be released in 90 days if prosecutors don’t decide to retry him, although an appeal could stall that. However, if prosecutors don’t appeal and win, they would be left with making a case based on … almost nothing. That’s because the confession was pretty much their whole case against Dassey (not entirely, but pretty much). Which is pretty telling.

In the Dassey case, the prosecutors’ centerpiece was Dassey’s March 1 statement to investigators Mark Wiegert (of Calumet County) and Tom Fassbender (of the Wisconsin Department of Justice). The prosecutor offered no forensic evidence (no hair, DNA or blood) tying Dassey, then 16, to the murder of the young photographer who disappeared after going to the Avery family junkyard in October 2005.

The Avery evidence was the reverse. Prosecutors built their case against Avery around a complex tapestry of forensic evidence they said tied him to the crime: Avery’s blood in Halbach’s car, which was found on the junkyard property; Avery’s DNA on Halbach’s car key, belatedly found in his bedroom; Halbach’s DNA on a bullet found in Avery’s garage that was consistent with a rifle hanging over his bed; Halbach’’s blood found in her own car; and bone and teeth fragments consisted with Halbach found with camera and clothing fragments in a burn pit and barrel in Avery’s backyard.

The defense tried to explain away the mountain of forensic evidence in Avery’s case by alleging that it was planted, perhaps with a blood vial stored at the courthouse from a previous wrongful conviction in a sexual assault (for which he spent 18 years in prison). They never offered any concrete evidence, though, that the blood was planted (and it’s possible, although not proven, that some of the DNA was "touch" DNA, not blood). Investigators deny planting anything.

The prosecution didn’t rely on confessions in Avery’s case because Avery didn’t confess: He denied (and still denies) that he did it. And, of course, Avery was an adult, well familiar with the criminal justice system; Dassey was a cognitively challenged juvenile with no prior contact with law enforcement.

Prosecutors also wedded the Avery forensics with many pieces of circumstantial evidence that did not exist in the Dassey case; for example, they had cell phone records, and they presented evidence that Avery asked for Halbach to come to the junkyard property using his sister’s name that day. Avery also had a cut on his finger. And there was evidence that he (and perhaps Dassey) had cleaned up something in his garage (Dassey himself testified to this at trial, but he said he didn’t know what it was). Not to mention the fact that bones and teeth consistent with Halbach were found in a backyard burn pit and barrel, and many people reported seeing Avery having a bonfire that day, a bonfire Dassey admitted in trial testimony that he was at (versus in a tainted confession). And so on.

There is a lot of evidence against Avery, and it’s varied evidence. In contrast, Dassey’s case seems to have operated on a "single point of failure" – those confessions (not all of which were presented in court at his trial). Prosecutors did have the statements his young cousin, Kayla, made to police. However, Kayla Avery recanted the statements at trial and said Dassey didn't make them to her. Still, her earlier statements to police remain a troubling aspect of the Dassey case: Did he at least see something? That’s a far cry from participation in murdering her, though.

The Associated Press wrote at the time, "Kayla Avery, 15, told her school counselor and then investigators that Dassey told her he saw body parts in a fire and saw Halbach tied up in a chair in Avery’s trailer." There are also Dassey’s statements in a recorded phone call to his mother, in which she asks, "So in those statements you did all that to her too?" and Dassey responds, "Some of it." The problem with that phone call is that one of the investigators urged Dassey to make it after the problematic interrogation. The statements Dassey gave were graphic and extremely detailed, albeit often contradictory and given after leading questions; however, if prosecutors don’t win on appeal, they can’t use it.

The prosecution didn’t use the Dassey confessions or call Dassey in Avery’s case; however, the confessions do have one nexus to the uncle’s case: People in the jury pool in Avery’s case told the court at the time that they had heard about Dassey’s confessions in the news. However, what matters in that legal judgment is whether those impaneled in the jury were able to set aside prior knowledge and feelings about the case. We will see what Avery’s new lawyer has up her sleeve when she files a brief in the case later this month.

Duffin said Dassey confessed involuntarily, citing many factors – including his age, the fact he had no lawyer or parent present, and his cognitive disabilities. Duffin also had sharp words for the investigators’ interrogation techniques, which he said included making false promises to Dassey, and for one of Dassey’s lawyers, who allowed Dassey to be interrogated without his presence.

The judge said Wiegert’s and Fassbender’s "collective statements throughout the interrogation clearly led Dassey to believe that he would not be punished for telling them the incriminating details they professed to already know."

"Especially when the investigators’ promises, assurances and threats of negative consequences are assessed in conjunction with Dassey’s age, intellectual deficits, lack of experience in dealing with the police, the absence of a parent and other relevant personal characteristics, the free will of a reasonable person in Dassey’s position would have been overborne," wrote Duffin.

Deeply troubling. As I noted in the book, "It’s not over for Brendan Dassey, either. His case is coming up in federal court. If there’s any potential for miscarriage of justice in this case, it’s hard to argue that it’s not his."

It’s time to correct it.

Jessica McBride spent a decade as an investigative, crime, and general assignment reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and is a former City Hall reporter/current columnist for the Waukesha Freeman.

She is the recipient of national and state journalism awards in topics that include short feature writing, investigative journalism, spot news reporting, magazine writing, blogging, web journalism, column writing, and background/interpretive reporting. McBride, a senior journalism lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, has taught journalism courses since 2000.

Her journalistic and opinion work has also appeared in broadcast, newspaper, magazine, and online formats, including Patch.com, Milwaukee Magazine, Wisconsin Public Radio, El Conquistador Latino newspaper, Investigation Discovery Channel, History Channel, WMCS 1290 AM, WTMJ 620 AM, and Wispolitics.com. She is the recipient of the 2008 UWM Alumni Foundation teaching excellence award for academic staff for her work in media diversity and innovative media formats and is the co-founder of Media Milwaukee.com, the UWM journalism department's award-winning online news site. McBride comes from a long-time Milwaukee journalism family. Her grandparents, Raymond and Marian McBride, were reporters for the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel.

Her opinions reflect her own not the institution where she works.