Seeing it months and months ago in the University of Minnesota Press catalog, I just knew that Doug Hoverson’s "The Drink That Made Wisconsin Famous: Beer and Brewing in the Badger State" would be worth checking out.

The Minnesota-based Hoverson is the author of "Land of Amber Waters: The History of Brewing in Minnesota," published in 2007, and if that was any hint, then his new book, which he spent more than a decade researching and writing, was bound to be notable.

Then, the advance reading copy landed on my desk in June with a thud and I realized I had no idea just how amazing Hoverson’s work would be. Seeing a finished copy in full color only further enhanced that sense.

With more than 300 pages of extremely readable, and beautifully illustrated narrative history of beer-making in America’s Dairyland, wedded to another 300-plus pages of what is basically an encyclopedia of every brewery that has ever existed in the state, "The Drink That Made Wisconsin Famous" has gone, in my estimation, from interesting read to essential reading for anyone interested in beer and brewing.

Earlier this month I chatted with Hoverson about the book and about brewing in Wisconsin and here’s what he had to say:

OnMilwaukee: Maybe you can start by telling me a little bit about the process of writing the book?

Doug Hoverson: Right now, my big one-liner is that it took less time to get Apollo to the moon than it did for me to get this book done. Once I finished the book I wrote on Minnesota, I took about a year off to relax and promote that one a little bit, and then I started to work on Wisconsin. Its been about 11 years from the first time I said, okay," I'm going to start work until now."

The Minnesota book is basically the same kind of format.

Yeah, it's very similar. It's obviously about half the size.

Let's talk a little bit about that; talk about why it's double the size. What is it about Wisconsin and brewing that seem to kind of click? Because we weren't always the biggest producer, were we?

No. There's a lot of really interesting things about Wisconsin brewing, otherwise I wouldn't have gotten 750 pages, but I think one of the things that really sets Wisconsin apart is you had a chunk of the really big breweries, Milwaukee giants plus La Crosse, and then you also had more of the really small breweries than any other state in the union, especially after Prohibition.

You had the ones that had the worldwide reputation and the ones that were really good handling a few dozen taverns in their neighborhood, and that created a really interesting local pride in both the big ones and the small ones, I think.

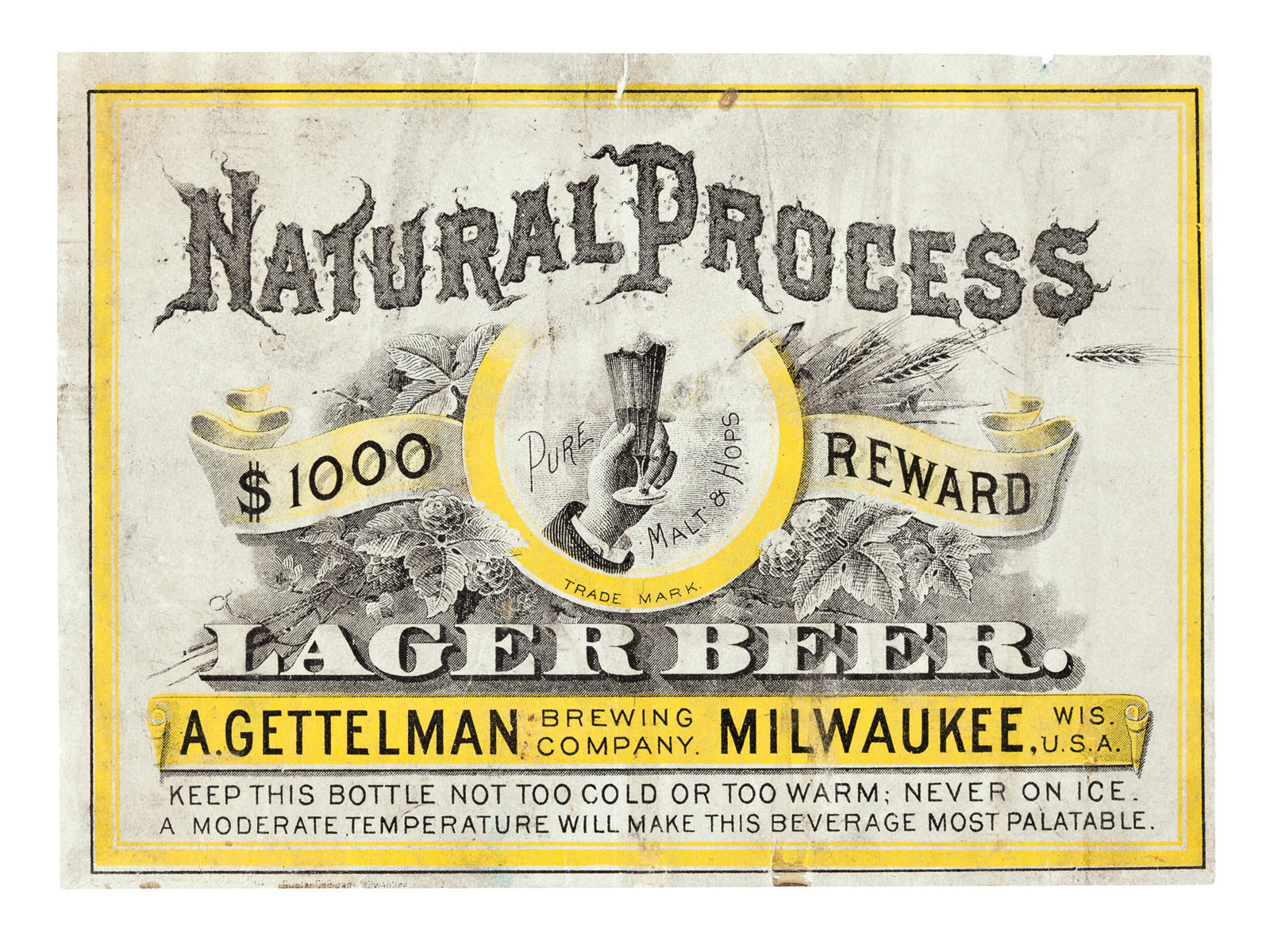

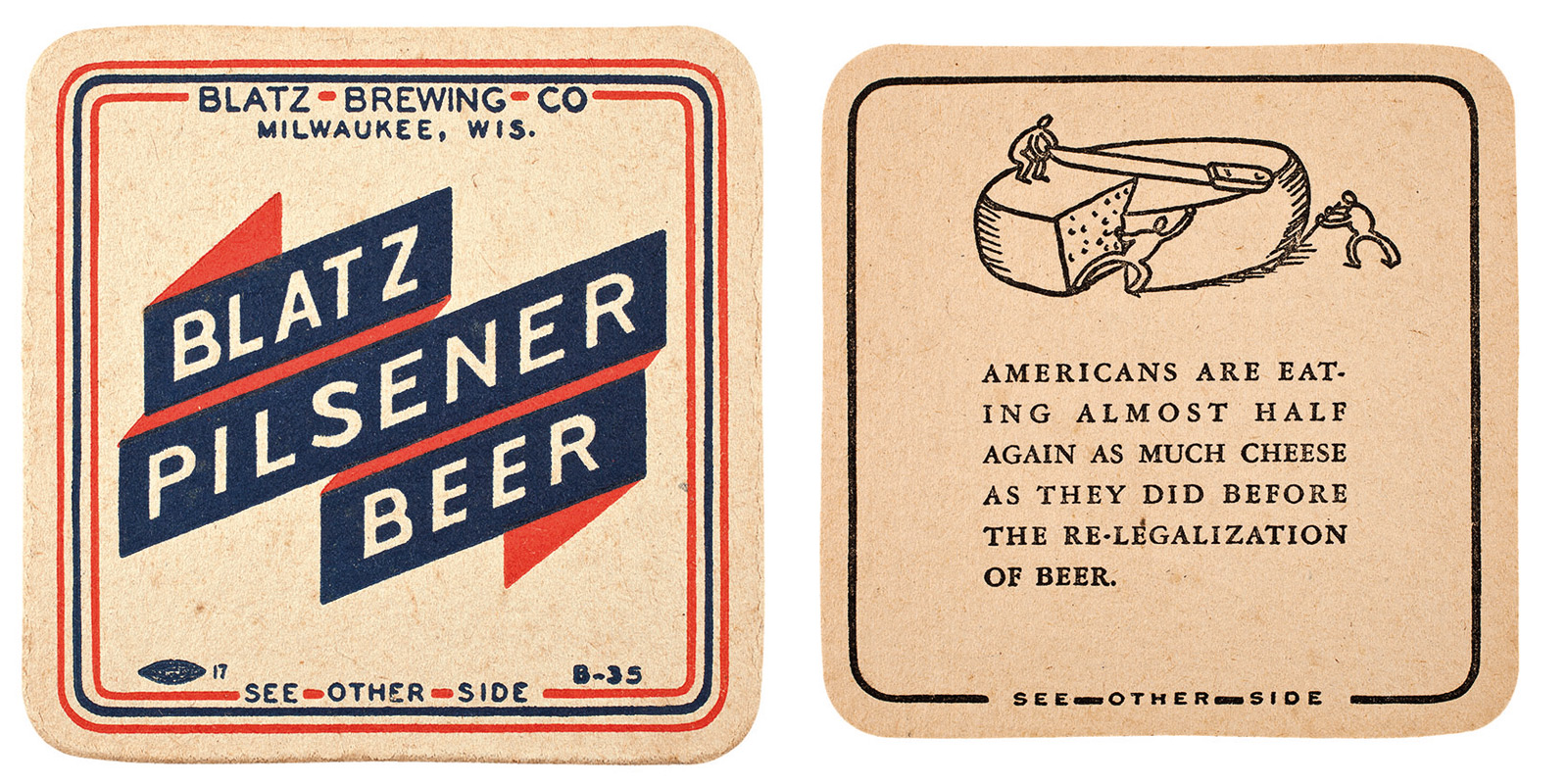

After the return of beer, Blatz issued a series of coasters that celebrated the contributions of

the brewing industry to the national economy. Another coaster in this series proclaimed that

brewers paid $1 million in taxes per day to federal, state, and local governments—$500 a minute

to the federal government. (PHOTO: Author's collection)

Is there a certain parallel with those small ones and the spike and craft breweries these days?

I think especially there is with the way that the craft breweries are starting to head toward being more neighborhood places with some distribution. Because I think you'll see that in most states there's only a certain number of the craft breweries that can get into that bigger state that can be a, say, a Lakefront or Sprecher. But you've got a lot of room for a smaller place that wants to be their neighborhood brewery and do a little distribution, say a Black Husky or something like that.

I think you saw that in the 1870s and '80s, and I think you saw that again in the 1930s to 1950s when there was still that interest in buying a beer from Plymouth or buying a beer from Eau Claire that still helped people in their neighborhood taverns.

It's interesting I think that Milwaukee and Wisconsin as a whole still has the reputation as being a center of brewing. We still talk about the beer that made Milwaukee famous and all that, but we're nowhere near that anymore since Pabst closed. We still have Miller, but a lot of that is made elsewhere. Why do you think we still have that kind of reputation even after Schlitz and Blatz and Pabst are gone?

Well, I think once you've built the reputation it stays as really part of the folklore and I think there's probably people around the country who don't even realize that some of those big brands aren't made here anymore. I think Pabst, no matter where it's brewed, is just going to be linked with Milwaukee. You had all those television commercials for years.

And Wisconsin has this reputation of a place where drinking beer is really an essential part of the culture and sure the old fashioned is a famous drink, too, but I think if you're shooting a movie or a TV show and you want to show Wisconsin people relaxing at night, they'll be drinking a beer.

That's not entirely incorrect.

No. Especially going through the period after Prohibition, Wisconsin hung on to draft beer longer than most other states. They were always the leader in how much of the beer was consumed on draft rather than bottled or canned. I think that speaks to the way that the old German beer gardens continued to make beer drinking in Wisconsin more of a communal sort of thing.

Was there one story – big or small brewery – was there one brewery that had a story that especially surprised you; that you didn't expect?

One that I found surprising was Oconto, and I really didn't know much about that going in. I knew that they had a brewery, but, reading up about it, they were actually a pretty major player in northeastern Wisconsin long after a brewery of that size in a town that size should have been. They really captured a lot of the Green Bay market, when there were still breweries in Green Bay.

They had a pretty innovative brewmaster there in the 1940s and '50s who had escaped Nazi Germany and come over and really done some great work with their beer and they punched way above their weight for years longer than they probably should have given the way the brewing industry was going.

That was the time, too, when, and maybe this is coming back with craft breweries, that you could actually make a pretty good living as a brewer just working regionally, right? If you could capture a chunk of northern Wisconsin, for example, you could do pretty well for yourself.

Yeah, you could, and a lot of places kept the lights on and kept their employees paid with the regional market. Some of those breweries, like Potosi closed in 1972, and Berlin, when it closed in 1964, they were still paying the bills. They weren't bankrupt, but they just saw that there was probably no way forward for more than another year or two and they decided to get out while they could still do so with pride and with integrity.

A post-prohibition tray advertising the Pelham Club and Pilsener brands.

(PHOTO: David Wendl collection)

What intrigues me about the book is the encyclopedic part,which had to be a massive effort. Why did you decide to do it the way you did it?

That was really kind of the template that we had set out with the Minnesota book, which obviously wasn't anywhere near as long a section. But one of the things I noticed about that Minnesota book was a lot of people that opened the book and immediately flipped to that second section to look up their hometown and see if I had anything in there about their old hometown brewery or even to find out if their town did have a brewery.

Part of it I think is a service to the beer history community. I've had a ton of people give me really great help on their hometowns or a town where they had some expertise and this is a way of helping get their research a little broader audience.

I think also I'm a little bit of a history geek and once you get into looking up some of these towns it really takes you down interesting history routes. I think it's really a nice way of showing that almost every little town did have a brewery and that they were all a little different and that the people in those towns supported the brewery, made it work and they're all different. You can't just say here's what a typical brewery was like. It's encyclopedic, but I think it's an important thing to preserve all of the stories at least to the point I can and still have the book be portable.

I write a lot about buildings and history here and I always say, because it's always been true, that I've never come across a building or a house that didn't have some kind of interesting story to tell. That section of the book really illustrates the same thing in the world of brewing, as you say.

Yeah, it does, and that's a ... and sometimes it is the story of the buildings and the people. One of the things I thought was really interesting, I think it's another good comparison to the craft beer era now, is that back in the 1800s the breweries were still a community meeting place. They'd have a taproom where you'd have a local political meeting or you'd have a local social meeting and there were a lot of those things very similar to today where they'll host a fundraiser or open it up for a local group to meet.

Are you going to do another book? Do you have another state in your view?

Well, we're thinking about that.

Because what would you do with all the free time otherwise?

Well, there is that, and I've been accused of not having much of a life. It's down to Michigan or Iowa right now. And Michigan has a little bit of a stronger case as breweries were a little bit more famous, but Iowa is a little bit closer to home and my son is going to the University of Iowa for a couple more years at least, so I'd have a place to crash if I was doing research trips.

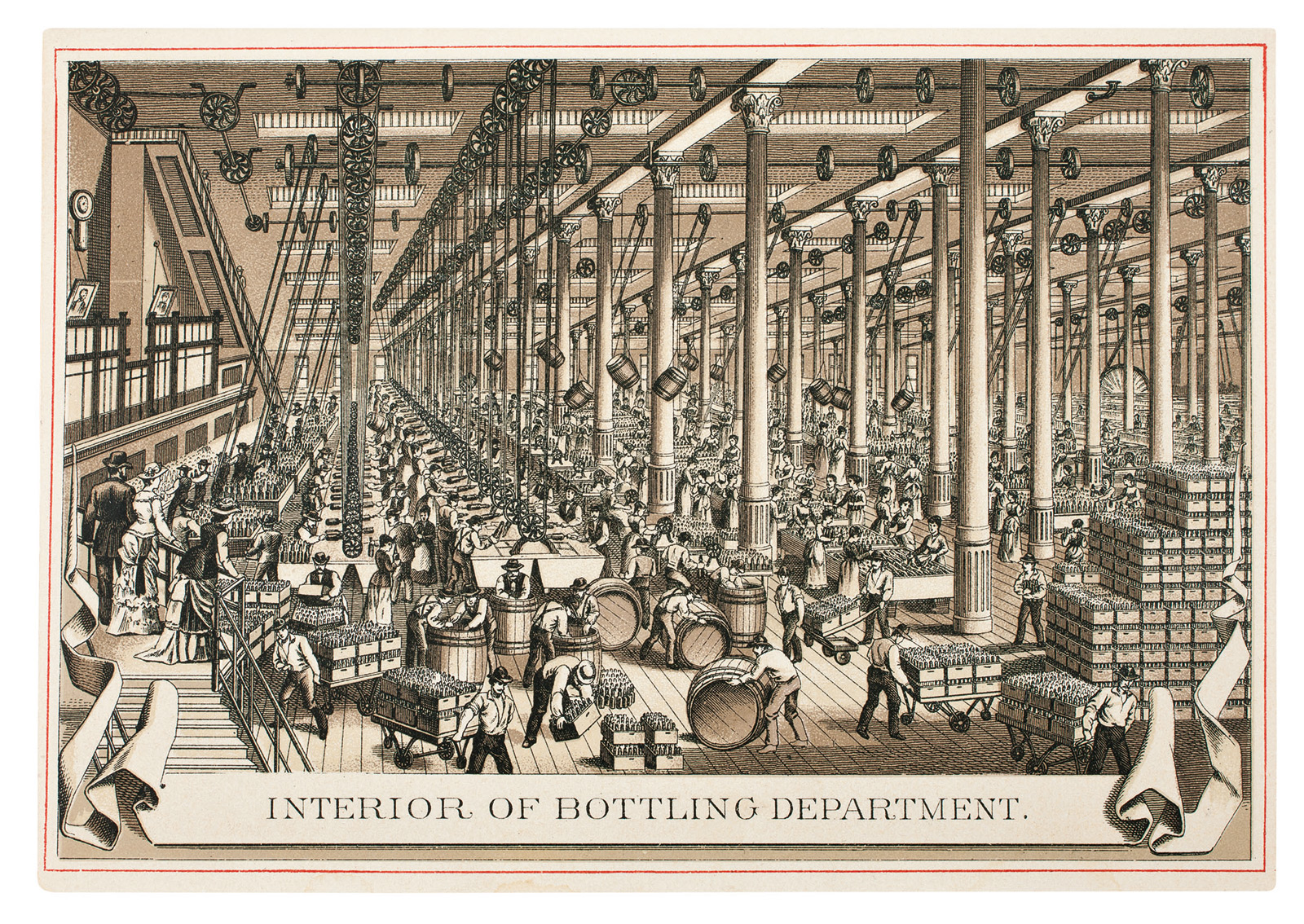

The bottling department of Pabst Brewing Co. as depicted in the Grand Army of the Republic souvenir booklet of 1889 was a marvel of industry. The engraver took special pains to emphasize the machinery that aided the entire process. Bottles are shown being packed into both barrels and cases. At lower left, several well-dressed visitors admire the efficiency of the plant. The engraving also shows the large number of women employed to label and wrap the bottles (and to attach a length of blue ribbon). (PHOTO: Courtesy of the author)

And you'd have access to a university library.

Right. But one of the things that's a big difference between the Minnesota book and Wisconsin book is the amount of old newspapers that have been digitized since I started working. And there are more good Wisconsin, mid-sized city newspapers in the type than for almost any other state. It was a huge help to be able to look up Sheboygan newspapers and Manitowoc newspapers and Janesville newspapers at home, so when I was doing research trips I could focus more on archival documents and things like that.

That's really changed the ability to do this kind of work, isn't it? Hasn't it?

Yeah, it has. It's really a dream world for me as a historic researcher. There's still some interesting work I can do in the archives and finding old family papers and court records and land records and things like that, but even some of that is starting to work its way online.

Okay. I have one last question for you because everybody's going to want to know. Do you have a favorite Wisconsin beer?

That's the question I've been practicing on how to dodge for years and years because, again, I've talked to so many of these brewers. What I usually like to drink is whatever the seasonal offering is. My rules are always drink the local and always drink the seasonal.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.