Ninety-two years ago this month, Johnny Mendelsohn won the biggest fight of his career and simultaneously sealed his fate as, in the words of a sportswriter who covered him, "the most maligned boxer Milwaukee ever had."

That’s because the guy in the other corner at the Auditorium on May 16, 1921 was the most beloved boxer (if not athlete) Milwaukee ever had.

By the time Mendelsohn moved here in 1916 from Canada, where his family emigrated from Romania when Johnny was a toddler, Richie Mitchell was already the handsome face of local boxing, a contender for the lightweight championship, and so adored that members of the "Mitchell Boosters" club frequently carried him bodily from the ring after a fight to the site of the victory blow-out.

Even though Mitchell was stopped by 135-pound champion Benny Leonard in their Jan. 14, 1921 championship fight at Madison Square Garden, he endeared himself even more by rising from three knockdowns and then knocking Leonard down in what is still rated as one of the most thrilling opening rounds in championship fight history.

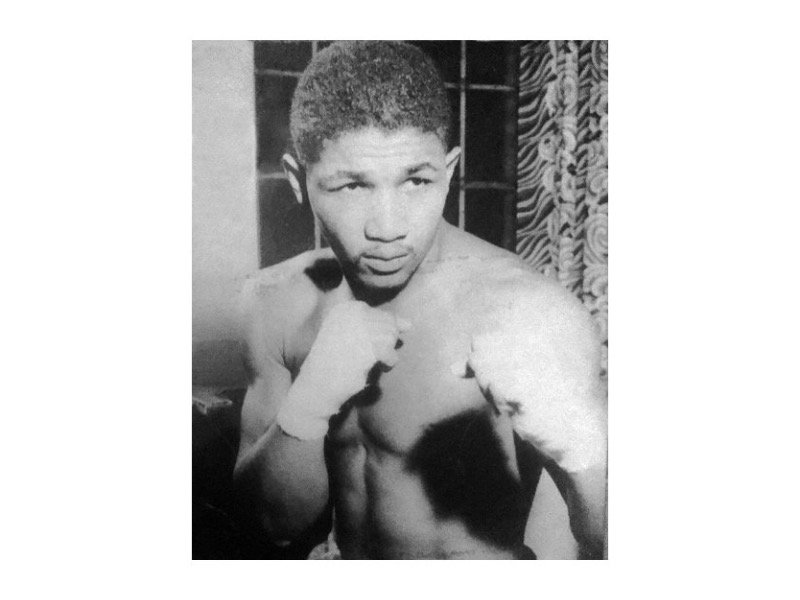

Since turning pro in 1917, Mendelsohn had provided plenty of thrills, too. They called the 5-foot, 4 ½-inch muscular lightweight the "Ghetto Hercules" and he slugged his way up the ladder with a wade-in style learned in turf wars with other newsboys in Winnipeg.

His favorite sport was swimming, not boxing. At 15, Mendelsohn won a national diving title in Canada. But there was no money in that, and while the hushed, appreciative crowds that watched him jackknife off the North Ave. bridge into the Milwaukee River every Saturday morning were nice, Mendelsohn preferred the howling ones that paid to see him make opponents splash in the local bucket of blood.

But he was inconsistent in the ring.

After he knocked out Eddie Mahoney on Oct. 15, 1920, Sentinel boxing writer Chet Koeppel hailed the "great victory for Mendelsohn."

Two months later, when Mendelsohn and Otto Wallace fought to a draw, Koeppel called him "an overrated boxer" and "simply a good boy among the fighters of the second-class."

So when Mendelsohn’s brother and manager, Harry, had the temerity to claim that Johnny and not Richie Mitchell was the best lightweight in town, it was an act of civic effrontery akin to taking a leak off the City Hall clock tower.

This is as good a time as any to say that the Mendelsohns’ ethnicity wasn’t exactly in their favor, either. "The Canadian Jew battler," one writer called Johnny; and Harry’s efforts to snare ever-larger purses for his brother were regarded as typical Hebrew avarice.

Yet when Billy Mitchell, who handled his brother Richie, demanded no less than a guarantee of $10,000 – the equivalent of $118,351 in today’s dollars, and many times over the 1921 average take-home pay of $1,537 – for a fight with Mendelsohn, it was considered a shrewd managerial move.

The Mendelsohn’s accepted, which meant that after Mitchell and the other boxers on the card were paid off and the Auditorium rent and all the other expenses were taken care of, Johnny got whatever was left.

It came to exactly $116.75. But with it went the lightweight championship of Milwaukee when Mendelsohn knocked Mitchell down three times in what The Journal’s Sam Levy said "reminded one more of a neighborhood battle for blood than of a formal ring bout."

"I have always said I could whip Richie, and I guess I proved it," said Mendelsohn after the exciting 10-round fight. "The satisfaction I got out of the bout more than repays me. I took a gamble, lost financially, but won the bout."

It sure didn’t win Mendelsohn any popularity.

"Every move made by the Lapham park resident serves to put him in a bad light with the public," wrote Levy after Johnny and Harry committed the cardinal sin of walking out of the Auditorium during a one-sided fight featuring Pinkey Mitchell, Richie’s brother, the following October. "The famous razz followed the pair from the building."

It followed Mendelsohn for the next five years, even when he fought with more courage than probably was good for him and put up some of the most thrilling bouts in local ring history. He became a contender for the lightweight title himself and in 1923 lost to Benny Leonard in Philadelphia, where they cheered Mendelsohn out of the ring for his display of guts.

But locally any acclaim for him was fleeting, and always overshadowed by the famous razz.

When Philadelphia lightweight contender Lew Tendler beat Mendelsohn in 10 rounds on Nov. 3, 1922, Levy wrote that the Auditorium crowd was disappointed not because the visitor won but because most of them "undoubtedly came to see the great Tendler stretch the unpopular Northsider on the mat."

"Johnny O’Donnell, a fighting Irish son, tamed Johnny Mendelsohn in their squared circle glove debate at the Auditorium Friday night while a mob of anti-Mendelsohn followers of the sport fairly roared themselves hoarse," reported Chet Koeppel on June 7, 1924.

It went on like that until Mendelsohn was back fighting in preliminary bouts for whatever purse he could get. He had to, because in 1925 he went bankrupt, the $50,000 he earned in the ring gone through bad investments.

He didn’t expect pity or any handouts.

"I’ll fight my way out of the present situation," declared Mendelsohn. "I’ll have to, I guess, because I want to pay every creditor."

He probably didn’t expect what happened, either.

The headline in The Journal after the overweight, over-the-hill boxer fought Billy Bortfeld in an eight-round preliminary at the Auditorium on Feb. 21, 1927 was, "Mendelsohn loses, but he gets his cheers at last."

"A far different atmosphere pervaded the arena when Johnny marched down the aisle, headed for the ring," wrote Sam Levy. "The boos and jeers which were so deafening in the days when he had the courage to meet such punchers as Rocky Kansas, Tommy O’Brien, Lew Tendler and others had turned to cheers. At last, Mendelsohn, now in bad financial straits, was acclaimed a favorite."

Mendelsohn died in 1989. His son, Jerry, lives on the north side and recalls his father as a man of few words.

"He used to tell me, ‘If there’s three or less, fight your way out of it. More than three – run like hell.’"

In his older years Mendelsohn swept floors at Allis-Chalmers. When the Great Blizzard of 1947 paralyzed Milwaukee, he walked from his home on Teutonia and North Aves. to the plant in West Allis and worked and slept there until the streetcars were running again.

At A-C , says Jerry Mendelsohn, there was a much younger and bigger plant worker who got his kicks taunting the gnarled old boxer, calling him punch-drunk and other names until the fed-up foreman finally said, "Johnny, I’m gonna turn my back. Do what you have to do."

"He laid him out like a bag of coal with two or three punches," says Jerry.

Even a Mitchell Booster would’ve cheered.