The flat file drawers that line the archives room at Milwaukee Public School’s Facilities and Maintenance Division on the edge of Downtown contain many artistic treasures. In most every case these are architectural drawings from the drafting tables of some of the city’s most respected and accomplished architects; men like Henry Koch, Edward Townsend Mix, Eugene Liebert, Herman Schnetzky, Walter Holbrook, Alexander Eschweiler and others.

But, in one drawer, there are plans for an unrealized school garden that are perhaps the most beautiful of all. These are the work of Milwaukee landscape architect Annette Hoyt Flanders, who worked all over the country, but whose story is rarely told. Even Wikipedia doesn’t have a entry for Flanders.

Fortunately, the archives of the Five Colleges (Amherst, Hampshire, Mount Holyoke and Smith Colleges and the University of Massachusetts Amherst) maintains a collection of Flanders’ papers and its website has a biography.

Born in Milwaukee in 1887, Flanders was the daughter of prominent lawyer Frank Hoyt, who kept a summer place out in Oconomowoc, where Annette spent much time. After earning her B.S. in Botany from Smith College in 1918, she got a Masters in landscape architecture at the University of Illinois. She also studied civil engineering at Marquette, here in Milwaukee, and design and architecture at the Sorbonne in Paris.

During World War I, she worked with the American Red Cross in France. In 1920, she joined the Vitale, Brinckerhoff, and Geiffert landscape architecture firm in New York, where she cut her teeth supervising plantings and doing design work. Four years later, she hung out her own shingle in New York, though she traveled often to Milwaukee, where she cultivated business.

Flanders did a wide variety of projects, including exhibit gardens, parks, subdivisions, private estates and other work, and in 1930 she was inducted into Home and Garden’s Hall of Fame. In 1932 the Architectural League of New York presented her with the Medal of Honor in Landscape Architecture. That same year, Richardson Wright, editor of "House and Gardens" magazine spoke of the "distinction and rare beauty" of Flanders’ garden designs.

Flanders appears to have done the work for the Maryland Avenue School grounds in 1918, based on the date on one of two drawings in the MPS archive. The only published reference I’ve found to the project was in a footnote in Cynthia Zaitzevsky’s "Long Island Landscapes and the Women who Designed Them":

"She designed the grounds of the Maryland Avenue School in Milwaukee, but the date of this project or whether it was done pro bono is not known."

During World War I, the school had a victory garden that earned newspaper space for pupils.

"Last spring," the Milwaukee Sentinel noted in October 1918, "the Maryland Avenue School started a war garden, upon a large, but stony and barren plot which spelled 'failure,' many thinking it would not prove a success. ... The pupils of the Maryland Avenue School ... have made a success of things that looked as a positive failure at the beginning."

This led the Oliver Chilled Plow Works of South Bend, Ind., to present the students with "some of the very best machinery and plows of the company," according to the Sentinel, which noted that the pupils were tasked with a little test.

This led the Oliver Chilled Plow Works of South Bend, Ind., to present the students with "some of the very best machinery and plows of the company," according to the Sentinel, which noted that the pupils were tasked with a little test.

"The same small boys who made so great a success of the war garden were asking to make a set of farming implements, consisting of a tractor, tractor plow, three hand plows, rail fence, split rail fence and whipple tree to illustrate the two methods as shown in the accompanying photograph (which showed both a motorized tractor and a horse-drawn plow at work in the garden). All these implements were made in the manual training shop.

"The boys had much fun in making the old rail fence and harness(ing) up the horses."

Their work earned them $25 from Oliver, and the children’s sale of the largest number of war bonds earned the school another $50 in Liberty Loan committee prize money. The Sentinel noted that the students planned to use the money to to "adopt" two more "little French orphans. ... Thus making a happy little family of six."

It’s unclear whether or not Flanders’ design was for this garden or whether it was planned for later. One of the drawings is described as a "Preliminary Sketch of Proposed Developement (sic) for The Maryland Ave. School." Thus, it’s also unclear whether or not her plan was ever implemented at all. A 1934 landscape plan for the grounds doesn’t offer any obvious clues in this mystery, either.

But it’s possible she did create the plan for the war garden as part of her larger scheme for the oddly shaped, roughly three-acre, bit of land upon which the school sits. Her site plan shows decorative planting on the east and west sides of the building and along the sidewalks on both Prospect and Maryland Avenues.

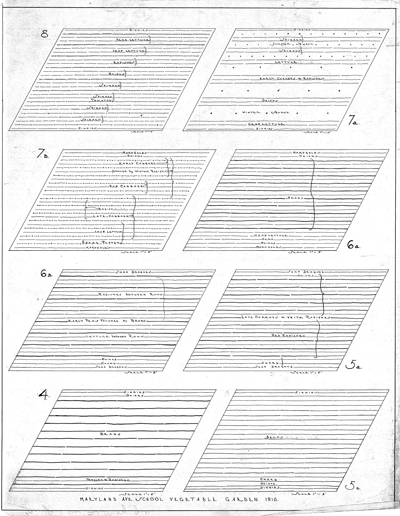

It also includes a gorgeous plan for the northern section of the property, which was delineated with a "windbreak of spruce." A sprawling girls play area, including a maypole, appears verdant and enclosed by trees and shrubs, with a pair of slender cedars flanking the entry. Adjacent, to the east, and separated by a hedge of lilacs were the garden plots – eight large beds.

Another sheet, apparently also drawn by Flanders, specifies the crops: early carrots, lettuce, spinach, chard, beans, radishes, onions and more, in beds framed in zinnias, marigolds and snapdragons.

Whether or not Flanders’ plan for what looks almost like a rural estate, on the expanding edge of a growing city, was built, it’s plain from photographs that by the 1940s, much of the land had been given over to asphalt, though some trees still appear to have dotted the grounds.

The rain garden at Maryland Avenue Montessori School. (PHOTO: Jenni Hofschulte)

The rain garden at Maryland Avenue Montessori School. (PHOTO: Jenni Hofschulte)

The current Maryland Avenue (now Montessori) School community has picked up the verdant spirit planted on the site by Flanders and by the World War I-era students, by creating a rain garden on the property, with the promise of more to come in the next couple years.

Meanwhile, Flanders focused her efforts on her hometown in 1943, moving her New York office to Milwaukee. She continued to design, but also to lecture and write about landscape architecture until her death, at her home on Prospect Avenue, not far from the Maryland Avenue School, in 1946.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.