There’s a couple things you learn when looking at the history of buildings. First, everyone thinks their big old home was once a rooming house and every barkeep is sure his place was a speakeasy during Prohibition.

And, of course, most folks think the place they live or work is haunted. As a rule, I’m skeptical, but if any place would likely harbor tortured souls and trapped spirits it would be this one.

While today, Milwaukee Health Department’s Southside Health Center, 1639 S. 23rd St., is a bright, cheery neighborhood clinic offering health advice, free immunizations and the like, this was once South View Hospital, built as an isolation facility for folks suffering from brutal contagious diseases.

The neighbors didn’t want the facility here and no one ever wanted to go to the isolation hospital – in less politically correct times dubbed the pest house – which is why they’d come and take you away and quarantine you against your will. And, perhaps worst of all, they’d take your sick children to suffer alone, without you.

Dale Byczynski, building and grounds supervisor at Southside, says he sees the apparitions every morning when he arrives before the sun comes up. He heads down to the basement and there they are.

"They’re always to the left, at the bottom of the stairs. I just see a blur of light and I wave and say, ‘Good morning, sir.’"

There are six of us seated around a conference table in what was the west wing of South View, built in 1916 (the slightly older east wing was razed in 1961), and no one appears to doubt Dale’s tale.

In fact, the others who work here nod knowingly, because they have stories of their own.

"The second floor, too," says Mary Jo Gerlach, the Public Health Nurse Supervisor who is also the building manager at Southside. "(People have) seen something up there, but the person who occupies the office right now doesn’t want to know about it. She freaks out. They were sitting up in the office a couple years ago and there was a shelf with a vase with some fake flowers in it. They were sitting and talking at the desk and they said the vase with the flowers didn’t just fall off the shelf, it was catapulted across the room."

"Someone in the TB department has a very vivid ghost story, too," adds business operations manager Yvette Rowe.

Byczynski takes it all in stride. "Oh, they don’t bother me anymore," he says, unaffected. "I just automatically wave."

But, still...

"One Sunday, I was coming to check the building," Byczynski adds. "I was on the elevator and it stopped (between floors). I’m the only one in the building. All of a sudden, I heard, "Can I help you?" I just about jumped out of my shorts. Well, here it was the City Hall operator talking (laughs). I didn’t even know that (emergency call) thing worked until that day."

As we take a group tour around the building, we’re on the lookout for signs. We visit the former wards, each of which opened on to its own screen porch. We even climb to the roof for a pretty great view of the Downtown skyline.

We look at where some walls were removed to open up the main waiting room space a few years ago. We marvel at the gorgeous woodwork around the transom windows and the great built-in shelving units that soar to the ceiling in some storage areas; so high that they have attached ladders to afford access.

In the basement, we search for signs of the tunnel that reportedly connected to the nurses' home across 24th Street (now home to Milwaukee Recreation's OASIS senior center) and we try to figure out which room was the morgue – figuring that’d be rife with swirling spirits.

We explore the crawl space under the northern portion of the building and we peek in at an old exterior staircase down to the basement that’s been sealed off from the outside.

But we don’t feel any shifting air or sense any ethereal otherworldly beings. Even later, when I’m going through the photos I took and I see an apparition peeking out from behind the basement incinerator (which would surely have gotten a lot of use in an infectious diseases hospital), it turns out to look more like a blurry version of Health Department communications officer Sarah DeRoo than a ghost.

From pest house to isolation hospital

But ghosts or not, the story of the building – and its predecessor – is an interesting one.

According to an internal report written by a superintendent of South View, "The early history of contagion and isolation is almost synonymous with the history of the city itself."

The city’s first isolation hospital – not-so-lovingly referred to back then as a "pest house" – was a log building rented in 1843 outside the town’s borders around what is now Oakland Avenue, near the site of UW-Milwaukee.

The place, run by the Sisters of Mercy, struggled to deal with epidemics like the cholera outbreaks that would alight in Milwaukee in 1849, 1850 and 1854. The victims of that dreadful disease were buried in shallow graves in a potters’ field on a triangle of land between Prospect and Maryland Avenues.

When a new schoolhouse was built on the site in 1887, Milwaukeeans were reminded of that by-then forgotten cemetery and the accidentally dug-up remains were re-interred at the old Spring Street burying ground. But they missed a few, because when, in 1950, excavation began on a gym addition for the school, more bones were discovered and removed.

According to the health department’s report, "In 1865 the City purchased 40 acres of land for $2,000 at the North Point of the city ... for a site for an isolation hospital (that) was never built. A portion of this land was later given to the Sisters of Charity in appreciation of their unselfish work in caring for patients during epidemics."

Other parts of the land would house a first ward (later 18th ward, and then Maryland Avenue) school annex, an orphanage, the industrial school for girls and other civic institutions.

As time passed – while the city relied heavily on the services of St. Mary’s and Passavant Hospitals – attention turned to the far southwest side as a potential site for a new pest house and in 1877 the Common Council spent $3,527.25 to buy just over six acres near what is currently 23rd and Mitchell Streets and approved $8,000 for construction of a new hospital.

But the new city hospital project was fraught with chronic controversy. First, the plans – by August Schattenberg – were deemed unworthy by the city’s health commissioner Orlando Wight, and, the competition was reopened. New plans were submitted to a panel of doctors, who preferred a pavilion-style plan, like one submitted by City Hall and The Pfister Hotel architect Henry Koch.

But the council demurred, saying the doctors were rooting for a general hospital plan that was not what the city was seeking.

"What the city wants," reported the Milwaukee Sentinel in April 1878, "and the council is legally authorized to establish, is an asylum for the patients who must be taken care of by the city, not on account of public charity, but to preserve the public health and safety ... the committee are in favor of the plan ... which they claim represents a hospital precisely suitable to the city's want."

Back in November 1877, the Sentinel described Schattenberg’s plan (a description that was reiterated in April 1878 when the council approved it):

"A cruciform foundation and superstructure of two stories. Each of the wings is to have a corridor so arranged that it can be shut off from its counterpart. The first story of the front wing is to be fitted into rooms for the physicians; dispensary, for visitors, and for the wardens and nurses. The wards for the treatment of contagious diseases are to be in the right and left wings, fronting to the south, and are to be provided with separate entrances from the outside, a ventilated hall affording the physicians, wardens and visitors ingress from the main or front corridor. The rear wing is to be fitted into dormitories for special diseases. There are also to be associated dormitories for convalescents. Each ward is to be provided with a bathroom and water-closet, and each is to have a separate system of ventilation.

"The entire second story is on the general plan of the first, and beside, it to afford room for officers and wardens off duty. The basement is to be partitioned for dining-rooms, kitchen and cellar. The dead-room is also to be located there, in the coolest part of the building, and is to have a separate ventilator, as in case of the other wards, the later so connected with lateral shafts that a change of atmosphere is ensured every 12 or 15 minutes.

"In the construction of the interior all corners will, so far as possible, be obviated. The windows will extend to the underside of the ceiling, and every other precaution will be taken to have the structure so ordered that there can be no considerable stagnation of air in any of the apartments.

"The rooms and wards are to accommodate about 60 patients, 40 of which may be smallpox patients, and the arrangement is to be such that the latter will be entirely separate from the wards occupied by patients suffering from other than contagious diseases.

"The building is to be of solid brick walls upon a stone foundation, and it is estimated that the cost will be from $7,000 to $8,000. In general appearance it will be plain and substantial. The plan admits of an unlimited extension on three sides without disturbing the present arrangement."

Despite Wight’s opposition – in her book, "The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform," Judith Walzer Leavitt notes that Wight had drawn up plans of his own, based on his ideas of medical science, for the new hospital and felt snubbed that the council hired an architect – the construction of Schattenberg’s cruciform cream city brick hospital went forward.

"When finished, its cost was between $8,000 and $9,000," notes the health department report. "It was built in 1878 ... and consisted of two floors. Over the front entrance the words were inscribed, ‘Public Health is Wealth.’ However, the plans were not in accordance with the demands of modern sanitary science."

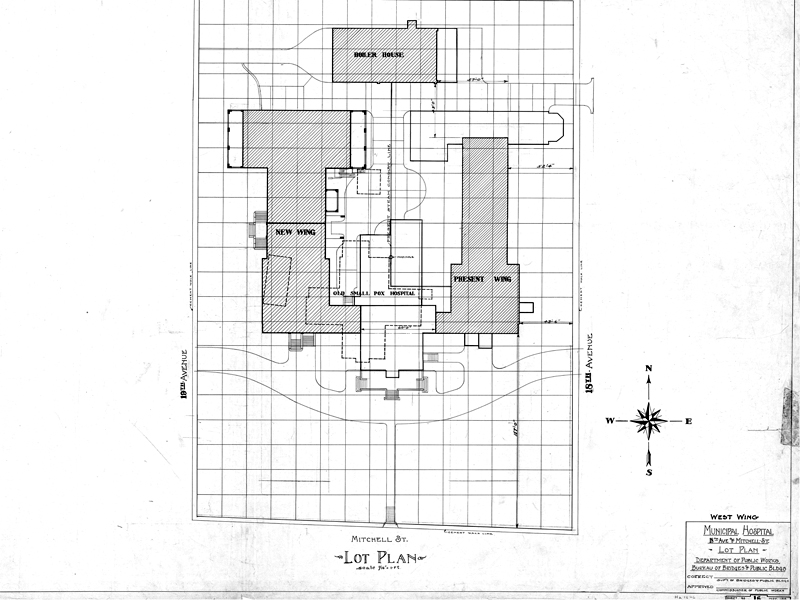

(Photo: City of Milwaukee Department of Public Works Building & Bridges)

Among its shortcomings, writes Leavitt in her book, the new hospital had no water or sewer connections. But, initially, that wasn't a problem because according to Dr. Louis Frederick Frank's "The Medical History of Milwaukee 1934-1914," the hospital, "remained unoccupied for a number of years, and as under charter provision it could only be used as a pest-house, it grimly waited for its season of usefulness."

It appears it first flung open its doors to smallpox patients during an 1882 epidemic, and the results were less than had been desired.

"Wight’s predictions about the hospital’s limitations proved essentially correct. Because of its physical deficiencies, the hospital rarely admitted patients," Leavitt writes, and within just over a decade, "in 1890, (then-health commissioner Uranus Owen Brackett Wingate) noted that the hospital was empty, in bad repair and ill-regarded among its 11th ward neighbors."

Those neighbors, powerless new Polish immigrants, were not happy to have an infectious diseases hospital among their homes. They wanted it moved out beyond the city limits.

There was talk of using the empty hospital as a school (Alexander Mitchell Elementary, across the street, wasn't built until 1894), and of selling the land and building a new hospital somewhere else.

Creating a model hospital

Instead, Wingate took action, building a disinfecting chamber, connecting to sewer and water lines, putting up a high fence, making major repairs and installing heating so the building could be used in winter.

While Wingate boasted that the facility was, Leavitt writes, "a model hospital," the neighbors were no happier and when there was a smallpox epidemic in 1894, they declined to go there, even though their Eleventh Ward was the most affected by the outbreak. In many cases, the sick were forced into the hospital. Even ailing children were torn from their parents and quarantined in the Isolation Hospital.

That same year, the health department report notes, "the hospital was filled to overflowing" thanks to another smallpox outbreak.

"Health officials maintained that the hospital was in good condition and offered good service to the sick poor who were admitted," writes Leavitt, adding, "whatever the actual condition of the hospital ... south-siders were convinced that it was a death house for those who went there as patients and that its presence infected the nearby districts."

On Aug. 5, 1894, when the authorities attempted to take an infected 2-year-old to the place, neighbors armed themselves in revolt. "About 3,000 'furious' people armed with clubs, knives and stones assembled in front of the child's house," Leavitt recounts. "Faced with the violent mob, and unable to control the situation, the ambulance beat a hasty retreat."

On one thing everyone seemed to agree. This hospital had no future.

In 1901, a second isolation hospital was opened in an empty existing county hospital building on 7th and Clybourn, and between 1903 and 1912, victims of outbreaks of scarlet fever and diphtheria were treated there.

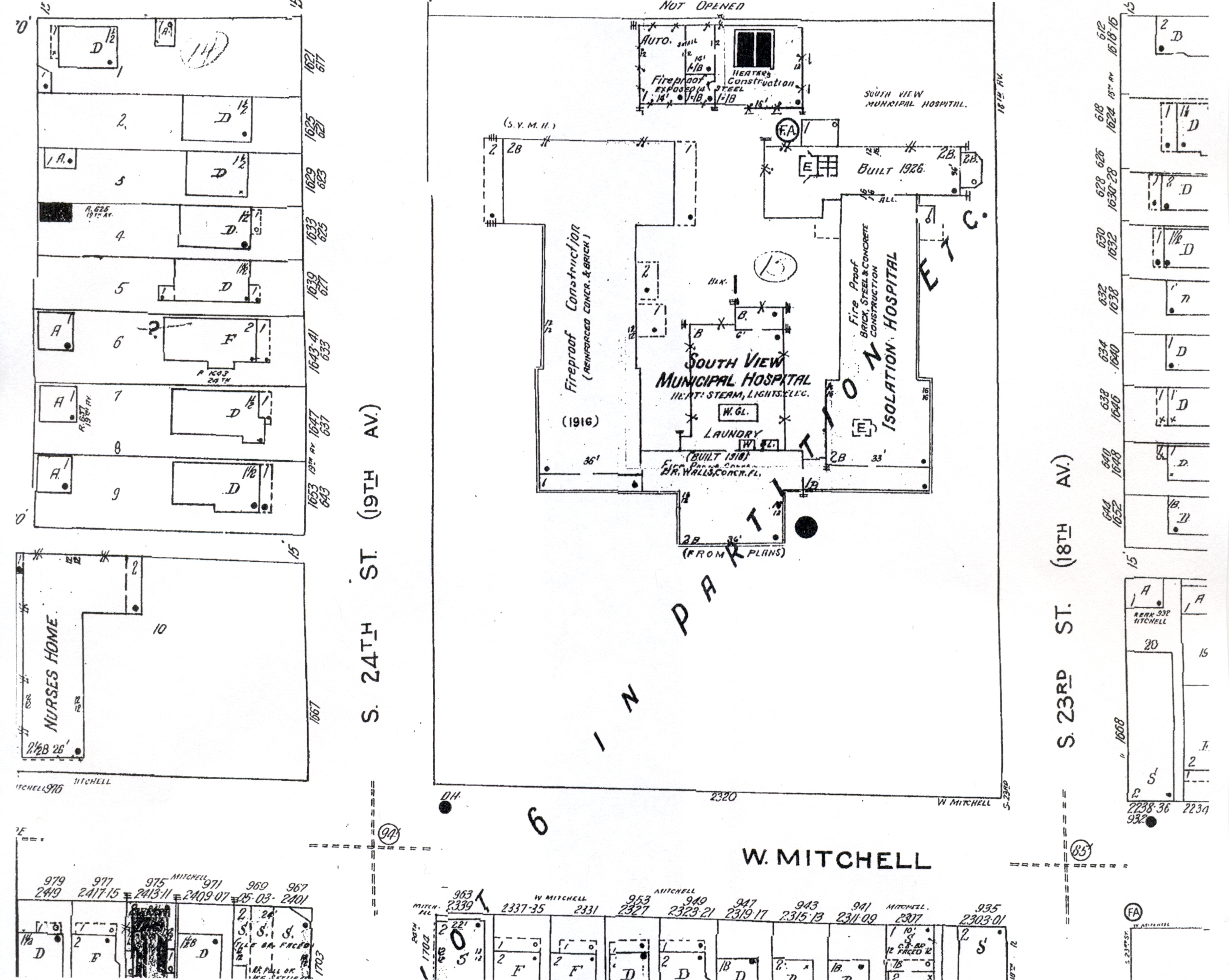

In 1911, the council authorized a $100,000 bond for a new hospital and the east wing of the building that stands now was begun. It was designed by municipal engineer Charles Malig, whose work stands all around this town.

Completed the following year, the east wing was opened – along with a garage and heating plant – and the patients moved from the 7th and Clybourn building, which was declared a firetrap and closed by the building inspector. When the west wing was completed in 1916, the old, unloved hospital building was felled.

Three years later, $130,000 was spent to build a central administration unit to connect the two wings. Hoping to erase the stigma of the name "isolation hospital," the new facility was dubbed South View Hospital.

It boasted screened porches for patients for whom fresh air was a must, doctors offices, classrooms, waiting rooms, a kitchen, laundry, laboratory, patient wards, staff rooms, storerooms and a nurses’ suite.

Most rooms had narrow but soaring 11-foot windows that admitted light and could be opened to provide beneficial air flow.

Schattenberg’s fate

The architect Schattenberg, however, didn’t live to see much of this. In 1880, three years after designing the hospital, the German immigrant – who had practiced architecture for 12 years – was elected secretary of the Milwaukee school board.

By 1889, the Milwaukee Public Schools were expanding so feverishly that Schattenberg was given an assistant and, soon after, "irregularities" began to emerge and in 1890 it became clear that Schattenberg had been embezzling school money, to the tune of $50,000 (roughly $1.3 million in today’s dollars).

The Chicago Tribune reported the incident, saying, "that this stealing of funds should have been going on for eight years without detection shows negligence of duty somewhere."

"Our Roots Grow Deep," a history of MPS written decades later took a subtler approach in describing the affair, saying only, "The School Board opened the year 1890 by amending its rules so that its funds would be deposited with the city treasurer. Previous lax financial arrangements and poorly defined procedures had led to serious loss."

But the most affecting account related to the entire affair appeared in the pages of the Milwaukee Journal on Dec. 7, 1889:

"Between 10 and 10:30 this morning Mr. August Henrich Schattenberg, secretary of the school board of Milwaukee, took his own life by shooting. ... The act was committed in the basement of his residence, 69 Reservoir Avenue, which he used as an office."

Schattenberg was found by his wife and a girl employed in the home.

"When the two women went to a window looking into the basement," the door to which was locked, "they were shocked and horrified to see Mr. Schattenberg’s face as pale as death and his head thrown backward, while the shirt front seemed to be burned as though by powder. ... A revolver (was) lying by his side and a gaping bullet hole in his left breast near the heart plainly told the story."

The Southside Health Center

Today, the Southside Health Center is no longer a hospital. It is not the place to go if you’ve cut your hand badly or are having chest pains. Instead, it’s a sort of a clearinghouse for a variety of health and human services.

There are Maternal Child Health Home Visiting programs and a community health access program. Folks can come in to sign up for Badger Care Plus, food share, child care assistance, Affordable Care Act enrollment and help with the WIC (Women Infant and Child) program.

There are nutritionists on staff, and neighborhood residents can get vouchers for healthy foods. There are safe sleeping clinics for new parents, who are given a pack and play and counseling on how best to lay an infant down to sleep. And there is a twice weekly walk-in immunization clinic.

"Then we have our men’s health program," says Gerlach. "A nurse for that program is here one day a week and she does blood pressure screening, cholesterol screening, you know, look at BMI, weight, and referring for services for that. We also have a Well Women program that’s here and provides screenings for breast cancer and cervical cancer, cardiac risk reduction ... it’s a non-profit agency that provides family planning … family planning health practices.

"A lot of people very feel comfortable with coming here so being able to provide a lot of different services. They know the building. They come here for different things. We can do pregnancy tests. We get a lot of phone calls from citizens about health department kinds of things. So anything that’s more on the "I need a resource" kind of thing, we have nurses that actually answer those.

"We also just started a program called Direct Assistance For Dads," Gerlach continues. "We have fatherhood specialists and they provide home visits to fathers who are either expecting or parenting a child under 18 months, which is kind of a first that, you know, focus on decreasing prematurity and infant mortality as well as, of course, having that connection with your children. So far, that program has been pretty successful. So we’re making some good impact."

One thing Southside doesn’t do anymore is quarantine patients with infectious diseases. In fact, it’s sort of the reverse these days. When I arrived for a visit, I couldn’t help but note with irony a sign on the door that reads, "If you have lived in or traveled to an area affected by Ebola within the past 21 days and have a fever and other symptoms, DO NOT ENTER THE BUILDING!"

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.