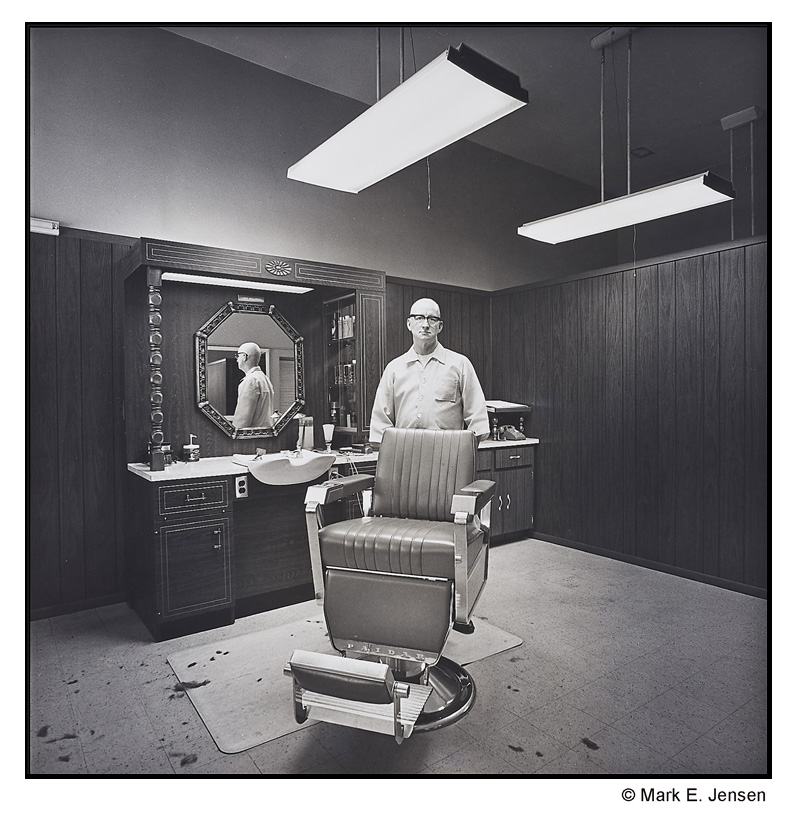

Maybe it's the stark interior, fresh-cut hair still dappled around the floor. The empty chair inviting you to sit down. Or the look on the barber’s face. His reflection in the mirror, offering us another angle.

Maybe it’s because I recognize the man’s name. Or because I was a longtime customer at this barber shop, though after it had moved upstairs to a new location and the barber in the photograph had passed away.

Whatever the reason, photographer Mark E. Jensen’s 1975 portrait, "Linus Mullarkey, Barber (East Side, Milwaukee, WI)" – a diamond among many gems in the "Portrait of Milwaukee" photography show that opened in September at Milwaukee Art Museum – just grabs me by the eyes and pulls me right in.

"The fine details of this portrait allow us to enter it with our eyes and imagine being there, whether it’s for a mundane trim or something more," says MAM Curator Ariel Pate, who assembled the works for the show.

"The empty chair in front of Mullarkey, with its footrest extending almost out of the frame, makes you feel as though you are about to sit down, and the barber’s reflection in the mirror reminds me of being at the hairdresser’s, when they hold up a hand mirror to show the back of your cut.

"Looking closely, perhaps the photographer just had a haircut himself – in contrast to the rest of Mullarkey’s shop, which is very tidy, there are hair clippings on the floor around the chair. To me, this portrait also has a surreal, almost science fiction feel to it – something about the octagonal mirror in the background feels like both a portal and a camera’s lens."

I definitely like the photograph, in part, because the photographer chose to focus on a hard working guy – a bald barber – just doing his job. The kind of everyday heroes that lenses often look right through.

Belleview Barber Shop, 2522 E. Belleview Pl., was close to my house when I started going there around 1990. The last time I visited – long after I’d left the neighborhood and just before its then owner John Szatkowski retired and went out west – was to get my haircut and snap some photos as my son got his first haircut. (Of course, I likely also convinced John to play us a tune or two on the accordion he kept in the shop so he could practice between customers.)

The Belleview Barber Shop building today.

The place means something to me.

And so does the name Linus Mullarkey – but not because it also, very oddly, happens to be slang for a lame excuse to slip out of an uncomfortable situation. Friends had told me stories over the years about Linus, so seeing his portrait enshrined in a big show at Milwaukee Art Museum resonated.

Mullarkey was born on May 4, 1920 to Benjamin F. Mullarkey and Mary Celia McNamara, who were farmers in Lansing, Iowa, just across the Mississippi River from De Soto, Wisconsin.

Linus was the second of seven kids.

"He helped to work the family farm until 1942, when he was drafted into the army and served until 1945, mostly in Persia (now Iran)," his son Jerry tells me. "He returned home to work the farm, but was soon married and looking for better opportunities. At that time, Milwaukee was the closest big city to that part of rural Iowa, so he joined a sister Rita and brother-in-law there."

Before heading to the Cream City, Linus married Joan Brannan in Harper’s Ferry, Iowa, where Brannan had been born five years after Linus.

Once in Milwaukee, Linus studied barbering at the Milwaukee Vocational School – now MATC – on the GI Bill, and in 1947 began working an apprentice under Art Bergstad, who had opened the Belleview Barber Shop in 1932.

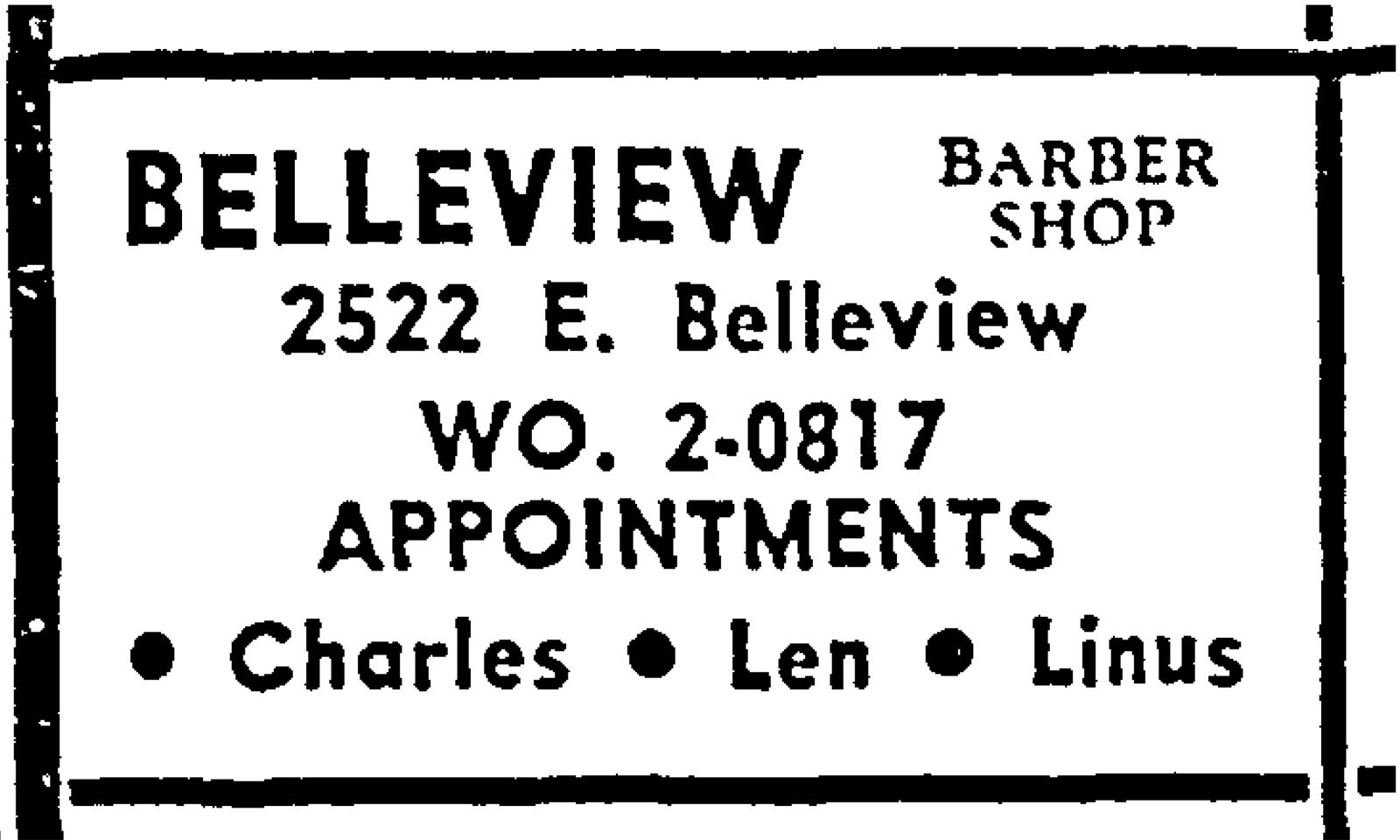

In 1953, Mullarkey bought the shop from Bergstad, and, says Jerry, his dad, "worked there for many years with at least two and sometimes three additional barbers. Business was good at the shop and almost all of his business was by appointment only."

But, says Jerry, home and work were separate worlds for Linus and they rarely collided.

"He never talked much about his work at home. As a kid, to me it seemed like he worked all the time, and it didn't seem unusual to us. I remember when barbers started taking Mondays off, and for the first time my dad had two days a week off from work.

"Occasionally he would mention the name of a sports figure or local TV/radio personality that had been in the shop, and it always surprised me. One time I rode my bike down to the shop during working hours and sat there while he worked. I was amazed at the amount of talking my dad did with his customers and the depth and breadth of his knowledge. I had never seen him like that at home."

1961 advertisement.

For years, there was enough business to support three barbers, but that began to change in the 1960s.

My friend Eric Beaumont was a regular as a child at Belleview Barber Shop, where his dad, Roger, also was a customer.

"The Belleview Barber Shop was a sacred place for my dad and me," says Beaumont. "Linus cut my hair from the time I was a little boy into my late 20s. He always let me pick a Tootsie Roll Pop from his abundant jar after every haircut into my late 20s. He had the friendliest voice, always slightly squeaky, like he had been singing opera really loud the night before."

My Belleview Barber Shop barber Szatkowski didn’t know his predecessor, but, he says, he’d always heard that Linus was "extremely cordial. Former customers, as well as (John’s) barber instructor at MATC, all commented on what a true gentleman he was. ... Well respected in the community."

By the 1960s, times, and hair lengths and styles, were changing.

"The ‘60s came and styles and the barbering business changed," says Jerry. "Eventually all of the other barbers retired or left, and my dad worked on his own. My dad took additional training to master the longer hair styles and women's styling."

In a 1973 newspaper article, Dave Milofsky wrote that the shop, "couldn't support multiple barbers anymore. Charles Lewis, retired in 1970 after 25 years and wasn’t replaced. Len Ulwelling, after 19 years, left to sell cars."

In his 1973 feature, Milofsky described the former digs in evocative detail:

"The shop consists of one large room dominated by four barber chairs," he wrote. "Along the walls are gray vinyl chairs for waiting customers, a cash register and a table crowded with sports magazines and a few Esquires and Newsweeks. On the walls are reproductions of paintings – picturesque fishing villages, hunting scenes, a country squire sitting before a glowing hearth with his dog. There are venetian blinds on the window and door, a stand up ashtray or two, and even a machine in the corner that dispenses bottles of Coke for one thin dime.

"Linus is flanked by wooden cabinets painted white and holding combs, brushes, hair tonic, shaving cream, talcum powder and other less familiar balms known only to the elect of the trade. A leather strop hangs from the side of his chair, and everywhere there seem to be mirrors which serve to emphasize his solitude. Wherever he looks within the shop he sees only himself reflected from one angle or another, and perhaps because of this he looks out the window instead. Until recently, Linus had seldom been alone."

Once Mullarkey was working alone, he no longer needed room for three chairs. Now, one, maybe two would suffice.

At the same time, the Downer Avenue Sentry grocery store that had opened in 1969 sought to expand into the three retail spaces that faced Belleview Place – including the Ivy House Dining Room and the pharmacy on the corner – and the building’s owner moved Linus upstairs.

But before that happened, photographer Mark E. Jensen stopped in.

"I had a part time job selling cameras and bus cards at Louie Ball's Card and Gift Shop around the corner on Downer Avenue," Jensen, who lives in Minnesota, recalls. "I just stopped in and asked for the proprietor. When I was told it was his place, I asked whether I might make a portrait of him. I was a graduate student at the time and may have mentioned that.

"My visit was not typical since normally I didn't walk in cold. Ordinarily I visited a small business at least once or twice before approaching the owner about making a photograph. As usual, I'm sure I had to answer a few questions justifying my existence and what I was really up to. Most often I simply said I was an artist and made photographs which sometimes ended up in galleries."

Jensen had arrived in Milwaukee in 1972 to attend graduate school at UW-Milwaukee and during his time here he co-founded Perihelion Gallery in Century Hall, was a board member of the Wisconsin Painters and Sculptors (WPS) andserved on the UWM film arts committee. At the same time, he shot portraits of professors, friends, people in their homes and, in one series, small business owners around town, including on Downer Avenue.

In 1975, there was an exhibit of some of these works in Milwaukee.

"My tendency with this body of work was to only make the exposure when I felt I had something. On leaving, I hoped I had produced a good negative," says Jensen. " I used a medium format single lens reflex camera on a tripod. As this was a time exposure, I made two frames and simply selected the one with the best expression.

"It seems there is something compelling about that particular photograph. Indeed, with the passage of time and my interest in recording shopkeepers who'd been around since before the war, in this case – these days at least – I may have caught a glimpse of a dying art.

"As with most of my work I try to create an image with aesthetic consideration. Indubitably light is an important element here. As well, at the time a fellow student remarked, with this image and others, about the presence of triangles in my work."

Though Jensen believes he likely gave Mullarkey a copy of the photograph, it’s possible the image never crossed the gulf between home and work.

"As far as I know, no one in our family knew about the picture," Jerry says. "To me he looks amused and a little sheepish that anyone would think that an honest man doing his job to the best of his ability would be unusual or worth any notoriety. My dad was a quiet, humble and, away from the shop, taciturn man. I think the picture captures that aspect."

Linus’ great-nephew Dave Brannan also remembers Mullarkey as the silent type.

"He was a very quiet guy, so I never knew him as well as I would have liked," Brannan recalls. "At family gatherings, the men would usually sit in the kitchen drinking beer, smoking and playing cards, and the women would sit in the living room, also drinking beer and smoking, but talking about their kids. Linus would sit with the guys, not drinking much, not smoking, and not playing cards – but you could tell that he was enjoying the company."

Brannan has also heard stories of Linus pouring customers shots of whiskey on St. Patrick’s Day, perhaps not surprising since Mullarkey’s grandmother was an immigrant from Northern Ireland.

Linus left barbering and the Belleview Barber Shop behind in 1988, when he retired. He and Joan took a long-anticipated vacation out east, vising New England and New York City.

But his golden years were not to be. Tragically, Mullarkey died in 1989.

"Almost immediately after retiring, he was diagnosed with lung cancer and died in May 1989," says his son. "My dad never smoked a day in his life, but was surrounded by second-hand smoke in his shop every day for 40 years."

So how did Linus Mullarkey’s visage come to adorn the walls of the Milwaukee Art Museum?

"A number of years after returning to Minneapolis in the late ‘70s I got a telephone call from a gentleman who had seen the image, perhaps in the Aperture publication titled "The Making of a Collection: Photographs from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts," says Jensen.

"Telling me he had had his hair cut for many years by Linus, he asked whether he could get a print. In fact, he purchased two, one for himself and another for the Milwaukee Art Museum."

Adds the museum’s Pate, "His work first came to our attention when Lisa Sutcliffe, the Herzfeld Curator of Photography and Media Arts, was doing research on the works that the Museum’s Photography Council (a group of Museum Members who support photography at the Museum) had helped add to the collection.

"This portrait really gripped Photography Council, so she managed to find Mark in Minneapolis, where he’s taught photography at St. Thomas and other schools since returning from Milwaukee. She visited to meet him and see his pictures from his time in Milwaukee, and we thought that the portrait of Linus Mullarkey, as well as the others of business owners on Downer Avenue would really fit well in Portrait of Milwaukee."

Jensen says that my fascination with the photograph is not unusual, because I have these various connections – although extremely tenuous at best – with its subject.

"With this and all my other work, I am most interested in people really looking and actually seeing something," he says. "Over the years I've found, through a classroom exercise called 'reading a photograph,' where the student writes about their encounter with an image, that every single individual 'reads' an image tempered through their own life experience."

I definitely believe that to be true, and I think it helps me look at the photograph and not just see a barber, or a small business owner, but a person who lived a life and had loved ones, had dreams, had ups and downs.

Digging deeper into the photograph and its subject, it also reminds me that these lives lived can leave a trail of sorrow and regret sometimes and it encourages me to be conscious of this with my own children.

"If I could talk to people about my dad and his picture, I would tell them that he would be a little embarrassed about any attention he was receiving," says Mullarkey’s son Jerry. "He considered himself an ordinary man doing dignified work with respect for his customers and colleagues. He provided a good life for me, my mother, my brother and two sisters.

"My main regret is that I did not know him better in an adult relationship. I left home at age 18 to begin college and soon was raising my own family. We never got to spend much time together as adult ‘friends’."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.