In honor of Black History Month, we're resharing this story – which first appeared in 2019 – of Louis Hughes, who escaped from slavery and ultimately came to Milwaukee where he became a well-known community member and the first African-American author in the city.

There he was staring at me from the backlit museum panel, illuminating my own ignorance.

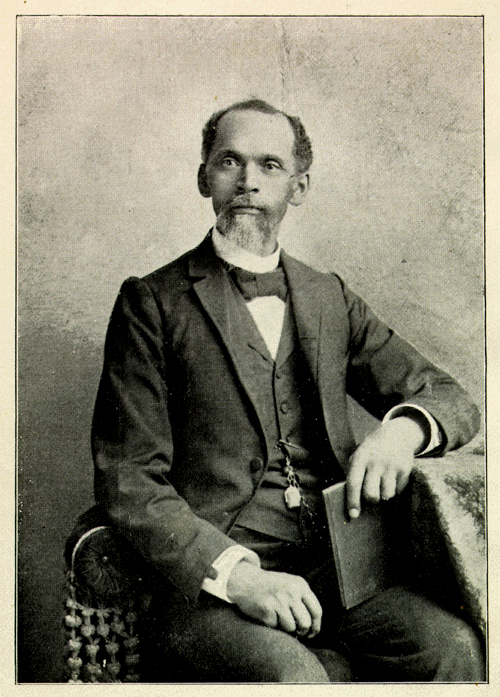

As boisterous school groups filed through the room, I stood looking at this face: dignified, with a hint of a smile. How could this be the face of a man born into slavery, separated from his mother and siblings as a child? The face of a man who witnessed – and experienced – countless horrors? Who escaped slavery, not once, not twice, but five times before finally finding freedom?

How could this man process that kind of struggle into such a serene gaze?

This was the face of Louis Hughes, author of the 1897 memoir, "Thirty Years a Slave: From Bondage to Freedom."

This was the face of Louis Hughes, author of the 1897 memoir, "Thirty Years a Slave: From Bondage to Freedom."

Louis Hughes, whose book (in which the portrait at left was included) was not only published in Milwaukee, but who lived here for decades. Who died here, and had been well-known. Who has been described as Milwaukee's first African-American author.

The panel describing Hughes was in one of the first rooms in the National Civil Rights Museum, located in the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where an assassin’s bullet ended the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. It is one of two historical places in the United States that have nearly brought me to tears (the other was Ellis Island).

"Mississippi slave seizes freedom by running away to meet the Union Army," it read.

"Louis Hughes was given to a cotton planter’s wife as a Christmas gift in 1844, at age 12. During the Civil War, Hughes fled to the advancing Union Army. Later reunited with his wife and child, he settled in Milwaukee as a successful nurse. He wrote his story in the 1897 narrative, ‘Thirty Years a Slave’."

In my 30-plus years in Milwaukee, some of those years studying local history, many more writing about it, I’d never encountered Louis Hughes.

As soon as I returned home, I found Hughes’ book at the Milwaukee Public Library.

"In my opinion, (it) is an excellent book," says Clayborn Benson, founder of the Wisconsin Black Historical Society. "It allows us into the everyday struggles of an enslaved person."

I’m not going to spoil for you what is a compelling story of determination and grit and triumph – as well as unimaginable pain and suffering – because I know you will read the slim volume. (The entire text is online here for free.)

But upon finding Hughes’ obituary in the Milwaukee Sentinel and reading that, "with the death Sunday afternoon of Louis Hughes, Milwaukee lost one of her most familiar figures," I wanted to know more.

Born into slavery near Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1832, Hughes was sold away from his mother at the age of 6. While enslaved by a family living in Memphis, Hughes attempted numerous escapes, always to be returned home and, usually, punished.

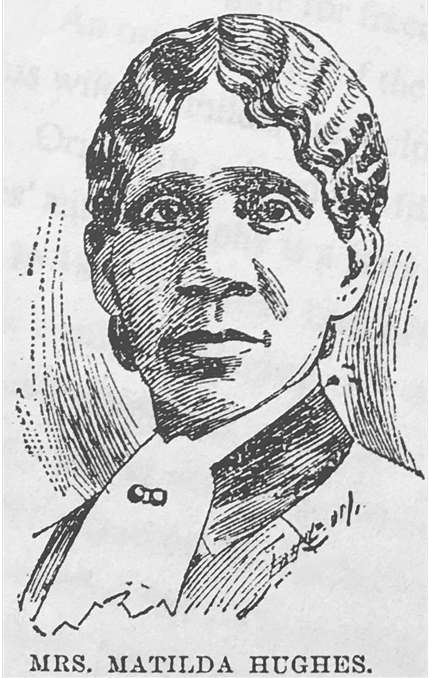

It was while living with this family that he married Matilda Tixley (whose portrait, at right, is courtesy of Milwaukee County Historical Society), who was born into a family that, by law, should have been free, but was instead illegally enslaved.

Matilda gave birth first to twins, who died, and later to another daughter. When Memphis fell to the Union during the Civil War, Hughes again escaped and used the lessons in medicine he’d been taught by his master to join the Union Army nursing staff.

Later, he returned to get his wife and daughter, risking his life to do so.

Their travels took them to Cincinnati and Detroit, and then to Hamilton and Windsor, Ontario, where, during the year spent there, two more daughters were born, and Hughes found work as a porter at the Iron House hotel.

"Our aim," he wrote, "when we left Memphis was to get to Canada, as we regarded that as the safest place for refugees from slavery."

During his time in Detroit, Hughes worked as a waiter at Biddle House. A stint as a sailor on the Great Lakes, traveling between Green Bay and Escanaba, led him to Chicago, where he found a job in the coat room at the Sherman House hotel and began attending night school.

It was at Sherman House that he met Milwaukee meatpacking magnate John Plankinton.

"During this time," wrote Hughes, "I saw many travelers and businessmen, and made some lasting friends among them. Among these was Mr. Plankinton. He seemed to take a fancy to me, and offered me a situation in the Plankinton House, soon to be opened in Milwaukee. I readily accepted it for I was not getting a large salary, and the position which he offered promised more."

When he arrived in 1867 – the year the hotel (pictured at right in an image courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library) opened – Hughes had "full charge" of the coat roam and, soon after, the bell stand, too, at the French Renaissance-style hotel that could house 600 guests in 400 rooms (before it was later further expanded).

Mathilda, meanwhile, "had charge of the waiter’s rooms, a lodging house situated on 2nd Street, one door from Grand Avenue."

Here, the hotel waiters occupied rooms on two floors and the Hughes family lived on another.

Later, Hughes was allowed to take home guests’ laundry to make extra money and that business became so successful that it moved to its own quarters at 216 Grand Ave.

By 1872, the Hughes family was living in a small back cottage on 4th Street, between Wisconsin and Michigan, owned by a Mr. Pearson of the Cream City Coal Yard. In May of that year, the Sentinel reported that, "Shortly after noon yesterday a fire was discovered in a barn in the alley west of Fourth Street. A brisk breeze from the west soon fanned the light structure into a dangerous pile of fire and flame. Adjoining the barn was the residence of Louis Hughes, keeper of the cloak-room at the Plankinton House. The building, a small frame cottage, was soon on fire, and it was with great difficulty that the household furniture was saved."

Hughes remained at the Plankinton for six and a half years, until 1874, during which time, the Sentinel later noted, "Hughes, and his story, became known to thousands upon thousands of travelers, many of whom took time to listen to his tales of the slavery days.

"Hundreds of men who are prominent in the business affairs of Milwaukee have during their childhood days gathered about Louis Hughes and heard him tell of the ‘old slavery days, when the black was the property of his master and could be sold as could a horse or a mule.’ Never was the former slave, when in a talkative mood, without an audience, and it was because of the appreciation of his youthful auditors that he was induced to set down the story of his life on the pages of the work which he called ‘Thirty Years a Slave'."

After leaving the hotel, Hughes continued to grow the laundry business, moving it to 713 Grand Ave., where, "the establishment ... was fitted up with all modern appliances but I was not so successful as I anticipated. My losses were heavy."

So, the Hughes family moved back to 216 Grand Ave. and, soon after, a friend recommended him as a nurse for an ailing Dr. Douglas. After a trip to the South, Hughes focused his energies on a new career.

"I liked nursing," he wrote. "It was my choice from childhood. Even though I had been deprived of a course of training, I felt that I was not too old to try, at least, to learn the art, or to add to what I already knew."

A recommendation from Douglas led to more work and more recommendations and, ultimately a successful career in medicine.

"To every true man or woman it is one of the greatest satisfactions to have the consciousness of having been useful to his fellow being," Hughes wrote in his memoir. "My duties as nurse have taken me to different parts of the state, to Chicago, to California and to Florida; and I have thus gained no little experience, not only in my business, but in many other directions."

During his years in Milwaukee, Hughes was active in St. Mark’s A.M.E. Church, of which he was steward from its founding in 1869 by Ezekiel Gillespie, until he passed away as the original congregation’s last surviving member. The church is now the oldest African-American congregation in Wisconsin.

In 1897, Milwaukee’s South Side Publishing Co., with offices on South 2nd Street in Walker’s Point, printed Hughes’ memoir, which was republished in 2002 by Montgomery, Alabama-based NewSouth Books.

"The volume is filled with his slave day experiences told in simple, eloquent language which has appealed to thousands," noted the Sentinel in its obituary of Hughes.

"The simple, unadorned language of this little book, which tells its sad story without comment or embellishment and apparently without vindictiveness appeals eloquent for the cause of the negro," wrote the Journal in an 1897 review, "arousing sympathy and indignation for the wrongs which the race endured so patiently for two centuries and should do much to stimulate an active interest in the future of the race in America" (before adding, incongruously, "the book contains a number of facsimile reproductions of confederate money").

The Hughes' were well-known enough in Milwaukee that in 1898, their 40th wedding anniversary was covered in the newspaper:

"Mr. and Mrs. Hughes in a quiet and unostentatious way celebrated on Wednesday at their home on the Port Washington Road. ... Both Mr. and Mrs. Hughes are in splendid health, looking many years younger than they really are. Upon receiving congratulations from his many friends, Mr. Hughes said, 'I have everything to be thankful to God for. Not only has He spared me and my family to see this happy moment, but He has given me a host of friends also. Yes, I can count my friends among some of the best families of the city. There is only one thing that bothers me and that is the way they are treating my people in the South. Well, I have lots of faith in God and in His time I believe that all that will pass away.'"

The 1900 census shows that Hughes was still in Milwaukee and still working as a nurse, though by five years later, he was described as a janitor.

In 1910, Hughes – Mathilda had passed in 1907 – and his daughter Charlotte were living with Hughes’ daughter Mattie and her husband Robert Gant – a former Plankinton House waiter by then working as a masseur at a natatorium – and their children at 2961 N. 9th St.

Louis Hughes died in Milwaukee in 1913 and was buried alongside his wife at Forest Home Cemetery.

The Hughes' daughter Lydia, who had been a music teacher and an organist at St. Mark's A.M.E., died in 1909. Charlotte, a seamstress and dressmaker, according to a Milwaukee County Historical Society exhibit press release, passed away in 1925.

Mattie continued to live in the 9th Street house after her husband's death in 1918, and she worked as a secretary and, later, a caseworker for the Milwaukee Urban League, retiring in 1938. She died a decade later.

Of course, I drove over for a look at the place on 9th Street.

While I was relieved to see the house, built in 1904, still stands, that relief was shortlived. You’ll be unsurprised to hear there is no plaque noting Hughes’ residence here, but that’s not even the worst of it.

The home – currently owned by the city – looks to be not long for this world. There are missing windows and holes in the roof. The door is boarded up and marked with a "no trespassing" sign.

I guess I’m not the only one who had Louis Hughes in his blind spot.

(Courtesy of Milwaukee County Historical Society)

Hughes’ book was referenced in a 1968 Milwaukee Sentinel article headlined "Early Negro Woes in City Recalled," and Milwaukee's African-American magazine, Echo, wrote about him the same year.

In 1993, the Milwaukee County Historical Society hosted a small exhibition about him, too, but beyond that, few traces of Louis Hughes and his remarkable story appear to survive in Milwaukee.

The Wisconsin Black Historical Society has a copy of the book, but nothing else about Hughes. MCHS has the book, too, and a few articles. Hughes isn't on the radar at America's Black Holocaust Museum, whose exhibits are not yet completely installed, and there's nothing to be had at Milwaukee Public Museum, either.

With 2019's solemn observance of the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans to Jamestown, Virginia, it seems only right that we should remember Louis Hughes.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.