The opinions expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect the opinions of OnMilwaukee.com, its advertisers or editorial staff.

This week in class, my students are reading this short post by writer Jamelle Bouie. Because most of you won't click through to read it – even though I told you it's short – here's the gist: Bouie sold a TV to a friend and, being a busy person, doesn't have time to take it to her until one evening around 10 p.m. She lives nearby, so he thinks he will just carry the TV over to her apartment.

Bouie, if you don't know him from TV or the internet, is black. You can probably guess where this story is going, or would have gone had Bouie not called his (white) friend and had her meet him at his apartment before the two of them walked the TV to her place together.

"I have no idea what would have happened if I decided to walk a nice TV three blocks down the street," Bouie writes. "It’s entirely possible that the police would have left me alone. But I couldn’t count on that."

What I like about Bouie's post, and one reason I have taught it for the last several years, is that it's a near-textbook classic argument of definition. It's not merely a narrative about selling and delivering a TV; rather, it's a narrative about what "privilege" is not. Bouie's kicker reads, "What does it mean to be privileged? It means not having to think about any of this, ever."

Milwaukee police last month provided me with a real-life, close-to-home example of this phenomenon, by detaining and searching state Sen. Lena Taylor's son for walking down the street delivering a frozen turkey to a neighbor's house. I mean, come on. A turkey!

Police protested, of course, that they were just following procedure, which puts me in mind of another narrative I often read with students, this essay (from 1999, so long before Ferguson or any putative but non-existent "war on cops" spurred by the Black Lives Matter movement) by African American actor and singer Alton Fitzgerald White.

In it, White tells the story of how he and "three other innocent black men" were detained, searched and, in fact, hauled to the local police station after cops were called about shady-looking Hispanic men in the lobby of White's building. Other residents protested that White lived there and that he should not be taken in, but that didn't matter. It also didn't matter that it was White and one of the other men who opened and unlocked the doors to the building for the officers, letting the police in to where the actual criminals were.

White recalls sitting in the station and recognizing that it was naive to believe police would let him go once they had the real bad guys. He writes, "When I asked how they could keep me there, or have brought me there in the first place with nothing found and a clean record, I was told it was standard procedure."

Like Bouie thinking about what might happen walking in his own neighborhood, or like what did happen to Sen. Taylor's son, White concludes with this thought: "I was told that I was at the wrong place at the wrong time. My reply? 'I was where I live.'"

I also thought of White's essay following the shooting death by police last month of an innocent Chicago woman, Bettie Jones, who, like White, had the temerity to open the door to her building and let police in to deal with an actual criminal suspect. Chicago police have responded that this, like what happened to White and Taylor's son, was a mistake and that they followed procedure (Chicago Mayor Rahm Emmanuel has since changed those procedures).

White knows the real answer, and, like Bouie and Lena Taylor, isn't afraid to say it. "It was because I am a black man," White says, italics his.

Just to be clear, I don't use these stories in class because I am on some kind of grand social justice crusade with my students – though you're welcome to think otherwise (and probably do). Both Bouie's and White's texts are well written and engaging for my students, and they draw solid lessons about writing from them. Besides, these narratives often mirror their own lived experiences, and my students are willing to listen to lessons about writing with these examples in hand much more than if they read some "classic" by EB White or George Orwell or anyone similarly pallid.

And, just to be clear, I also know that these stories are stories we hear because they are not the norm. Almost all the time, almost all police officers do their jobs with care, professionalism and a non-discriminatory bent. As often as it seems these things happen, thousands of perfectly fine interactions between police and public of all races and persuasions happen every day without incident.

But my point – and I do have one, I promise – is that if we wanted to talk about privilege, if we wanted to have an honest discussion about it means right now in early 21st-century America to be white or to be black and to deal with authority and the righting of wrongs, now is the time to do it.

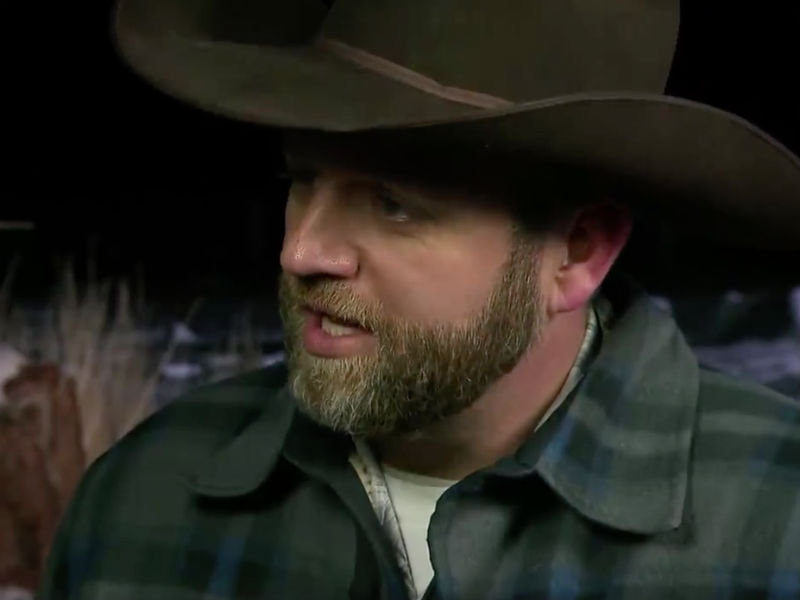

Because as I write this, heavily armed, reactionary, right-wing militants have taken over a federal building in eastern Oregon with publicly expressed plans to seize federal land and use it as a base of operations to oppose, to "kill and be killed" as necessary, they say, and evade the laws of the U.S. government.

Those domestic terrorists are white, and they are in Oregon right now because the last time they did this, taking over federal and threatened federal officers in Nevada, they were not arrested, detained, searched, shot, prosecuted or otherwise faced with consequences under the law. The leader in Oregon is Ammon Bundy, the son of Cliven Bindy, the Nevada rancher who defied the law and led an armed insurrection against federal authority.

Contrast that with the Occupy Wall Street protests, or any of the protests in Baltimore, Chicago, Missouri, even Milwaukee after the Dontre Hamilton shooting and decision not to charge the officer, where peaceful, unarmed protesters were arrested and charged. Not all protests or protesters were peaceful, certainly, but the record is clear that many peaceful, unarmed people – even media covering those protests – were arrested.

Cliven Bundy, not peaceful and heavily armed, is alive. Ammon Bundy is alive. Jared and Amanda Miller are dead, but were alive long enough after being part of the armed Bundy insurrection to kill three people, including two Las Vegas police officers. Every single Bundy Ranch armed protester was allowed to leave alive without even a trespassing charge.

Bettie Jones opened her door and is now dead. Tamir Rice had a toy gun in his pocket and is now dead. Laquan McDonald, Eric Garner, Samuel DuBose, Freddy Gray and hundreds of others you've probably also never heard of are dead, though they were unarmed and, in many instances, not even close to posing a threat.

I know I am not the first to say it, by far, but there is no greater or clearer illustration of what it means to be privileged in America right now than this: Armed white militants repeatedly have threatened government agents and taken over government facilities and been allowed to live, to leave consequence-free. Unarmed black men and women and children go about their everyday lives and are shot dead, or fear they will be.

If you've read this far, I feel you probably deserve something more than nothing, but I'm sorry I have no answer to the problem. It's been America's peculiar burden since before the Revolution. But it would be nice if as a nation, we could acknowledge the fact that there is a problem, that privilege still exists in this country and our refusal to deal with it has consequences. Deadly ones.