Even with the primetime landscape dotted with "reality" shows, you get a sense that the TV industry could use a reality check. Virtually everything you see on the tube these days looks ridiculously easy.

In the time it takes most of us to open a can of paint, remodeling experts turn houses from drab to fabulous.

Aided by hyperactive trainers and nutritionists, gigantic people shed dozens of pounds in an effort to become "The Biggest Loser."

Complicated diseases are diagnosed, treated and cured by teams of good-looking doctors who are often trying to sleep with each other.

Court cases -- argued by impeccably-dressed, silvery-tongued lawyers -- go from preliminary injunctions to jury verdicts before top-of-the-hour news break.

And then, there are the cop/crime shows...

Don't even get us started on the ones that provide DNA results faster than most drive-thru jockeys can super size Combo No. 3. We're talking about the nightly shoot-‘em-ups, where bullets seem to fly constantly but neither policemen (at least those in starring roles) nor innocent bystanders seem to get injured.

That's not reality. What happened to Dan Deibert late last year of the Milwaukee Safety Academy, while not 100 percent real, seemed a lot closer.

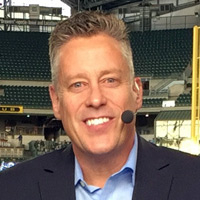

Deibert's hands were shaking and his heart was racing. His mouth was dry. Beads of sweat glistened on his forehead. Though he is usually lightening quick with a quip, the co-host of "The Morning Spin" on radio station WISN (1130 AM) struggled to answer a few simple questions in the immediate aftermath of his participation in a "Shoot/Don't Shoot" simulation similar to one that police officers encounter during firearms training.

Just two minutes earlier, holding a paintball gun at his side and covered virtually head to toe in protective clothing, Deibert stood at the end of a makeshift alley. Roughly 21 ft. away stood a similarly protected training officer, his back turned to the radio host.

When given the go-ahead by Sgt. Jim MacGillis, the range master at the academy, Deibert gave the "suspect" an order.

"Police! Get on your knees and put your hands on your head!" Deibert yelled.

When the "suspect" failed cooperate, Deibert reiterated his commands, his voice was loud and somewhat forceful but quaking with nerves and adrenaline.

"I didn't do anything," the suspect said, his back still facing Deibert. "Why are you hassling me? What did I do?"

As Deibert repeated his command, the "suspect" turned and sprinted toward him with a knife. Deibert fired his weapon a few times; the suspect turned and ran away, with at least one of the paint pellets hitting him in the back.

The action lasted just a few seconds and when it was over MacGillis peppered Deibert specific questions about the encounter.

Why did you shoot him?

How many shots did you fire?

You said he had a knife. Which hand was he holding it in?

What color was he wearing?

What did you say to him? What did he say to you?

MacGillis grabbed Deibert's hand, which was trembling, and checked Deibert's pulse, which was racing. Though he'd scarcely moved during the drill, Deibert was perspiring. ("I was wearing a lot of gear," he said later. "Come on, I had that big codpiece on.")

MacGillis said that Deibert's reactions were similar to those experienced by street officers, though on a much smaller scale. Deibert came away with a new appreciation for situations that officers face.

"I was in a lit area and I knew the guy was going to turn on me and it still scared me a lot. I was scared blankless," he said.

"I was amazed how quickly he got to me. It was less than 2 seconds. I thought I was a pretty good distance from him, but I didn't know what the guy has in his hands or how he was going to react.

"I thought I was ready and he still got to me a little bit."

The 21-ft. distance was not an accident. MacGillis cited studies that said in the time it takes the average officer to recognize a threat, draw his sidearm and fire two rounds at center mass, an average suspect charging at the officer can cover a distance of 21 ft.

MacGillis also pointed out that it can take four or five shots to hit a moving target once and that there are recorded incidences of suspects being hit multiple times and still advancing to kill police officers.

"These decisions are made in a split-second," MacGillis said. "And, they can be the difference between life and death."

Most police officers spend their entire careers without firing their weapons in the line of duty. The Milwaukee Police Dept., which has nearly 2,000 sworn officers, had five officer-related shootings in 2006.

On TV, the cops and bad guys often take part in broad daylight, not dimly-lit hallways, shadowy side streets or dimly-lit alleys. On TV, cops involved in shootings are not assigned to "administrative duties," and their supervisors seldom get bogged down in paperwork to determine whether the discharge of a firearm was justified.

Deibert, who has watched more than his share of cop dramas, always knew things portrayed were unrealistic. He didn't have a notion just how sanitized they were until he participated in the exercise organized by Anne E. Schwartz, the public relations manager for the Milwaukee Police Department.

"I knew that cops had a tough job," Deibert said. "You see on TV and in the movies you think "That's easy." In real life, you know it's tougher."

Although some studies show it can take an average of five shots to hit a moving human target, Deibert connected with two or three shots, including one that hit his ‘assailant' in the back.

"You hear people say 'How can you shoot someone in the back?'" Deibert said. "I did it. I wasn't aiming at his back and I wasn't planning to shoot someone running away, but it happened. I don't think people realize that or allow police to make mistakes. At the same time, I also think a lot of times the cops are unwilling to admit ‘I made a mistake.'

"Mistakes are going to happen. In a controlled situation like I was in, it's nearly impossible to maintain your composure. Now, you throw in low light, in an alley, and other noise and the fact that it's life or death, mistakes are going to happen. I'm still amazed at how quickly things happened."

Joel McNally, co-host of "The Morning Magazine" on WMCS (1290 AM), got to sample that speed during his stint at the Citizens Police Academy.

"When you get the idea of how quickly things happen you get a better understanding," McNally said. "Some of the things citizens think are unrealistic, like ‘Why didn't you shoot the gun out of his hand?' or "A gun beats a knife. Why are you killing someone?'

"While (the demonstration) gives you an idea of how quickly they can close the gap, I also think in a way the police may be expecting too much in certain situations. They are trained to fire until he threat is gone. That means they can empty a gun into a person and the person is still coming at them. I suppose that is possible and once happened, but I don't think that is normal and it has kind of lead them to consider everybody to be a monster."

That wariness can manifest itself in some gruff interactions between police in citizens, but Deibert thinks it's better than the alternative.

"The thing that scared me most after doing (the demonstration) is cops that are afraid to shoot," he said. "When you pull someone over for speeding, you just don't know how people are going to act.

"You hear people dealing with police officers say ‘Well, that cop was rude to me.' Well, you might know you aren't a threat, but the officer doesn't know that."

That's one of the reasons Schwartz brought the media together for the exercise.

"We wanted to give people a feel for how quickly things happen and what goes into the training of these officers," she said.

Host of “The Drew Olson Show,” which airs 1-3 p.m. weekdays on The Big 902. Sidekick on “The Mike Heller Show,” airing weekdays on The Big 920 and a statewide network including stations in Madison, Appleton and Wausau. Co-author of Bill Schroeder’s “If These Walls Could Talk: Milwaukee Brewers” on Triumph Books. Co-host of “Big 12 Sports Saturday,” which airs Saturdays during football season on WISN-12. Former senior editor at OnMilwaukee.com. Former reporter at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.