Compare a photo of the Miller Cafe – which operated briefly, but with great popularity for fewer than two decades at the dawn of the 20th century – with how the building appears today and you’ll likely be disappointed by the contrast.

That’s not a slight on today’s building, 753 N. Water St., which is well-maintained and attractive.

But, built as a tied house by the Miller Brewing Company and designed by the brewery’s go-to team of architects, Wolff & Ewens, the designers were so enamored of their stunning work, with its domed turret, arched windows and main entrance, that they moved their offices to its second floor.

I’m always happy to see the striking turret dome whenever it pops up even in the margins of a vintage Milwaukee photograph.

The Miller Cafe, circa 1905. (PHOTO: MillerCoors)

Alas, by 1920, the beer had dried up everywhere in the United States thanks to the Volstead Act and the lavish architectural detail on the building’s exterior – some of which required permission from the Common Council to include because it encroached on the air space above the sidewalk – suffered a similar prohibition and was stripped off, turret included.

Though it only served as a tavern for about 15 years – another victim of the 18th Amendment – the Miller Cafe was home to a few larger than life Milwaukee personalities and businesses.

Early days on the northwest corner of Mason and Water

But, first, let’s go back to a time when the Miller Cafe building didn’t yet exist.

In the late 1860s, we know that a three-story brick commercial building previously stood on the site and from about 1867 it was home to Edward Keogh’s printing business.

According to Elmer Epenetus Barton’s 1886 book, "Industrial History of Milwaukee, the Commercial, Manufacturing and Railway Metropolis of the North-west" ...

"In the first rank of Milwaukee firms we find the name of Mr. Edward Keogh. In 1867 he established a small business, with a few cases of type and one press. The superior quality of work turned out soon established a reputation second to none, and the large increase of orders compelled him to add to the facilities of his house from time to time, until he now occupies two floors with his printing and ruling departments, has three modern printing presses and a four-horsepower Otto gas engine, and a fine stock of the latest styles in type. He employs 10 workmen, and has an extended trade through the state. He makes a specialty of job and book work, and has also a book-bindery in connection."

Keogh, born in Ireland in 1835, arrived in America in 1841 and in Milwaukee the following year, noted Barton.

"That he is deservedly popular among his acquaintances is shown by the fact that he has represented the 3rd district in the assembly for nine years, having first been elected in 1860. In 1862 and 1863 he served as state senator, having been elected by a good round majority. He is now the city printer."

Two views, courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library, that show the building that pre-dated

the Miller Cafe, one from the 1870s and the other from sometime between 1895 and 1903.

Also in the building from as early as 1868 was druggist Charles von Baumbach, whose pharmacy would later move to locations up and down Water Street, Broadway and Market Street, before becoming Yahr & Lange Drug, which, in 1968, moved to Elm Grove from its home at 141 N. Water St.

By the early 1880’s, well-known local attorney George Kurtz kept offices upstairs, in rooms that in the coming years would house other lawyers, realtors and professionals. In 1881, Keogh was still printing downstairs, but it seems not for long.

In 1883, Milwaukee’s long-lived bookseller C.N. Caspar, which had a few locations over the years, opened in what was then 437 East Water St. (Plankinton Avenue was then called West Water Street) and remained until 1903, when the building was razed to make way for a new structure. At that point it moved across the street into the Brodheads Block on the southwest corner.

Perhaps most important of all, Frederick J. Miller, who arrived in Milwaukee in 1855 and immediately became active in the brewing game, opened a saloon on the northwest corner of Water and Mason Streets by 1857.

The means the new structure was a return to roots for Miller.

Miller Cafe is born

That new structure is the building we see today, more or less. There have, as I’ve said, additions and subtractions across the years. But the bulk of what mason John Schramka laid remains intact.

The building, which seems to have immediately been dubbed the Miller Cafe building was open by November 1904. This we know thanks to a notice in the Nov. 18 Milwaukee Journal, which reported that Curtis and Mock lawyers "removed" from the Herold Buildings to "6-7-8 Miller Cafe building, northwest corner East Water and Mason Streets."

MillerCoors’ Corporate Archivist Dan Scholzen tells me that in 1907 Sam Trimmel ran the cafe, but the name of the original cafe owner seems lost to history. It’s possible that Trimmel had been there from the start, but a 1906 newspaper advertisement is ambiguous on this point, though it suggests Trimmel was new.

"Miller Cafe has been reopened under the management of Sam Trimmel, announcement of formal opening later," read the announcement.

The place must’ve been a fun one.

A classic 1905 photo that pops up around town periodically – a big print of it can been in the Fiserv Forum – shows a group of men and boys outside the cafe, presumably welcoming the horseless carriage bringing barrels of Miller from the Valley brewery.

An elaborate sign announces the cafe and a beautiful Miller sign, perhaps 6 or 7 feet tall, adorns the south facade. The windows are topped with striped awnings. In the turret windows on the second floor you can see painted: "Wolff and Ewens, architects."

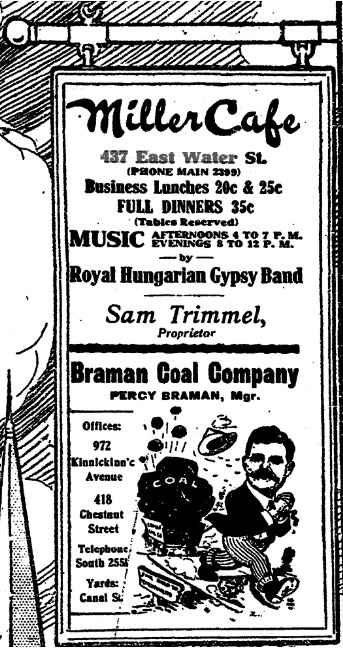

In June 1907, the cafe offered "business lunches" for 20 and 25 cents, full dinners at reserved tables for 335 cents. There was live music by the Royal Hungarian Gypsy Band daily from 4 until 7 p.m. and 8 until midnight. A 1906 ad describes The Harmony Trio, which used a zither in its performances at the cafe.

By 1911, former 12th Ward Ald. Robert Buech was the barkeep, and his son Arthur was among the bartenders on staff. Buech, born in Poland in 1870, also ran Pleasant Valley Park in Greenfield. After a number of failed attempts to get elected to state and local (in Greenfield) office, Buech, a Socialist, would become Milwaukee County sheriff and a county supervisor.

On Oct. 17, 1914, the Milwaukee Press Club – which was among the Miller Cafe building’s first tenants when it opened in 1904 – left for the Jung Building a few doors to the north.

You can spy the dome in this 1914 photo. (PHOTO: Milwaukee Public Library)

According to the Dec. 7, 1914 issue of the Press Club’s "Once a Year" newsletter, the club moved out on Oct. 17.

A November 1914 issue of the Bell Telephone News reported, in the quirky inside-joke style of a tight-knit club, "You to whom her name is sacred, newspaper men of the past and present, you who escorted her with fitting pomp and ceremony to her present temple 10 years gone by, and you who have come but recently to the shrine that was builded by the hands of your predecessors, are now called to attend Anubis upon her second pilgrimage. The time is 7 p.m. at sunset of Saturday, the 17 day of the current month; the place the old Milwaukee Press Club rooms at 437 East Water Street; the occasion the Hegira of the Sacred Cat, with all fitting pomp and ceremony to the new quarters on the eighth floor of the Jung Building, 457-459 East Water Street, where articles of good cheer will await the guardians of Anubis at the end of their pilgrimage. Selah.

"For the above insight into the life of the Press Club of darkest Milwaukee we are indebted to Alonzo Burt, who, while president of the Wisconsin Telephone Company, became so impressed with the empressement of the representatives of Milwaukee’s press that he was pressed into membership in the Press Club, from which organization he has never been ex-pressed."

Yes, the mummified cat you can now see in the Press Club’s current home on Wells Street, just off water, is THAT old and spent a decade living above the Miller Cafe before being ritually paraded up the block to its new home.

Early the following year, Buech moved to a new tavern on 3rd and State.

Louis Holzfurtner – who was born in Munich around 1876 and arrived in Milwaukee at age 10 – who had run the Forst Keller Restaurant at the Pabst Brewery from 1907 until early in 1915, took over the Miller Cafe and ran it as a tavern and restaurant until the arrival of Prohibition, which went into effect in January 1920.

At that point, it appears he ... well ... continued to run it as a tavern and restaurant.

"Louis Holzfurtner, proprietor of the Miller Cafe, East Water and Mason Streets, and one of the best known of the downtown saloonkeepers, was arrested late on Friday by federal officers on a warrant charging violation of the national prohibition act," read a March 6 newspaper report.

"Despite the fact that Holzfurtner’s friends were ready to furnish $2,000 in cash for his release immediately after his arrest, they were informed, it is said, that a real estate bond was necessary, and that cash, or Liberty Bonds, would not be accepted. It was impossible to complete arrangements for this real estate bond Friday night, and have it approved by the federal authorities, wheretofore Holzfurtner was held at the jail in the custody of Sheriff Robert Buech, proprietor of the Miller Cafe before Holzfurtner took over its management."

Yes, the former Miller Cafe landlord arrested the barkeep that followed. One can’t help but wonder if there was some bad blood involved or if, on the other hand, the two sat around the jail and reminisced about the place. Oh to be a fly on the wall that day.

Holzfurtner said he was innocent and though papers said he declined to talk to reporters about his arrest, they proceeded to report what he told them:

"He maintained that his cafe and bar had been only open for the sale of soft drinks and meals since the Volstead Act was put into effect. He pointed out that his place was one of the first of the downtown cafes to close up at an early hour after the prohibition act, stopping the sale of wines and beer containing 2 3/4 percent of alcohol, became effective. Holzfurtner has been in the saloon business in Milwaukee for many years."

Despite his self-proclaimed innocence, Holzfurtner pled guily to selling liquor and was fined $100. He told the press that he intended to retire from the tavern game.

Prohibition brings change

That May, Miller sold the building and new owner Morris Fox remodeled it, removing the architectural details that made it so striking.

The building in a grainy 1922 shot that shows the changes made to the exterior.

Among the tenants at that point was John Meyers, who, one newspaper reported, ran a "barber shop (that) has been for many years the tonsorial headquarters for Milwaukee newspapermen. Meyers will move his shop June 1 to the lobby of the Iron Block."

Like Meyers, Holzfurtner moved on, taking a space across the street at 410 East Water and with then-partner Adolph Binder open The Louis Restaurant on July 31.

"After many weeks of preparation we are now ready to announce the opening of our new restaurant," read a July 1920 advertisement. "Our preparations have included obtaining the very best service. Home cooking exclusively. All food served will be be prepared in our own bright, clean kitchen. Other features are a home bakery, delicatessen, candies and soda fountain."

And, proving that we have not cornered the market on nostalgia, "Our food takes you back to the good old days of home cooking."

But a fire in February 1921 was not helpful to the start-up and the owners lost $7,700 in canned foods, tobacco stock and restaurant furnishings.

A 1922 article about how Prohibition and the growing popularity of the automobile combined to shift Milwaukee’s nightlife out of town noted that the building, formerly a hot spot, was remodeled into a "modern office building occupied by a leading investment house."

That company was the Morris F. Fox & Co. investment company founded in 1914 in the Wells Building and which by 1922 had 40 employees.

Fox himself was born in Dane County in 1883 and took a position with Interstate Light and Power in Galena, Illinois, in 1908 and staying two years before heading to Chicago to work at Byllesby & Co. In 1913, he became that company’s representative in Milwaukee, but quit soon after to start his own company.

In 1923, Holzfurtner followed the nightlife shift out of Milwaukee and spent six years running the Sandy Beach Hotel on Beaver Lake in Hartland where guests could enjoy all the comforts of "a modern family resort," including boating, bathing, fishing and Sunday chicken dinners.

After Repeal, Holzfurtner returned to Downtown Milwaukee to work as a brewery rep for Chicago’s Atlas Brewing. In 1938 he had the Buildings Cafe at 774 N. Broadway and in his waning years – he died in 1953 at the age of 77 – he’d run McCann’s Tavern at 800 E. Michigan Ave.

Many years later, in 1971, the Sentinel’s Jaunts with Jamie column recalled Holzfurtner via a letter from his daughter, but not for his Miller Cafe days:

"Louis, as he was always affectionately called, always had a pleasant smile and a glad hand for all of his many friends. The Forst Keller at that time had a red tile floor. The ceiling and lower side walls were dark, highly polished wood paneling, with matching bar and backbar. Mounted deer heads hung higher on the walls to carry out the forest cellar feeling. On one wall there was a large, beautifully carved cuckoo clock and next to it the mounted head of a buffalo. The chairs were of a lovely dark wood and in the back of each a heart-shaped design. Potted palms were scattered here and there. There was entertainment every night. Mr. Holzfurtner went to Chicago and auditioned musicians and entertainers he hired. Businessmen known as the ‘round table group’ would meet there each noon and lingered to discuss politics and other matters until late in the afternoon. Mrs. Holzfurtner’s free lunch made the Forst Keller a popular place during the day."

The Fox Co. remained at the Water Street site for a few decades, sharing the building with Callan-Kassuba Realty for many years before giving way to Empire Federal Savings and Loan in the 1940s. The bank merged with Guaranty Savings and Loan in 1970 and, the following year, moved to "modern facilities" at 400 E. Wisconsin Ave.

The building in 1957. (PHOTO: City of Milwaukee)

A series of businesses came and went over the following years, including notably, Milwaukee Cloak and Suit Co., a women’s ready to wear retail store, which was founded in the building to the east on Mason Street in 1912, and which opened on the corner in 1976, staying 20 years.

During that era, in 1983, the building’s owner, Carley Capital Group, wanted to raze the entire block along the west side of Water between Mason and Wells, keeping only the facades and building new structures behind them. In the end, this plan failed, leading only to the razing of the Jung Building (you remember, the place where the Press Club moved after leaving the Miller Cafe).

After Milwaukee Cloak closed, Hunter-Zigman, a marketing firm moved in, and in 2003 Bruegger’s Bagels brought retail back to the corner. The following year, the building was sold to Dermond Associates. In 2016 Bruegger’s closed and afterward The Angry Taco briefly operated in the space.

It is curently vacant, and I'm sorry to report that it's been decades since you could get a business lunch for anything like 20 cents there.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.