The building at 2140-50 N. Prospect Ave. isn’t large, but you can’t miss it because of its striking exterior.

Built in 1934 as headquarters for the Milwaukee-Western Fuel Company, the building was designed by hometown architect Herbert Tullgren, who drew a two-story Art Deco gem of a building.

Constructed of buff brick, the facade is lined with vertical orange terra cotta columns, striped at the top and bottom, that flank the windows. Spandrels between the first- and second-story windows are adorned with terra cotta reliefs that depict three scenes from the life of coal as fuel: mining, shipping and shoveling.

Though there are more than three panels, there are only three designs, which are repeated on three of the building’s four sides. The spaces below the first-floor windows are a repeating pattern in terra cotta.

In his great book, "Architectural Terra Cotta of Milwaukee County," Ben Tyjeski calls the building the architect's "ultimate terra cotta masterpiece."

Perhaps Tullgren designed a building he’d personally enjoy seeing since he spent a lot of time in the neighborhood.

Tyjeski notes that the terra cotta was created by American Terra Cotta and Ceramic Co. in Crystal Lake, Illinois, about 45 miles northwest of Chicago.

The Tullgrens

Herbert got his start in his father Martin’s firm and between them – and Herbert’s brother Minard – they designed buildings of all kinds, all over Milwaukee, including the George Watts building on Jefferson and Wells, the Commerce Building on 4th and Wells, the art nouveau-influenced multi-story indoor parking garage on Mason and Water Streets, the Savoy Theater on 27th and Center, the Sherman Theater even farther afield on Burleigh and the eye-catching multi-storefront retail building on the southeast corner of 60th and North, the Moderne headquarters for Badger Mutual on the South Side, and the elaborately decorated West Milwaukee High School, to name but a few.

Tullgren the younger had his office in his home at 1234 N. Prospect Ave., and the family’s work fills quite a large amount of East Side real estate, from the stunning Art Deco tower at 1260 N. Prospect, to the Shorecrest Hotel, the Moderne Hathaway and Viking apartment towers on Kane Place, the Downer Theater, the gorgeous Bertelson Building (home to Strange Town restaurant now and the Avant Garde Coffee House in the 1960s), the building that houses Good City Brewing, and – directly across the street from 2150 N. Prospect – a large warehouse that’s now a self-storage facility and the corner tavern that’s home to Vintage bar.

Again, these are just a few examples of many, many projects the Tullgrens designed in Milwaukee and beyond.

Martin Tullgren, a Swedish immigrant, had arrived in Chicago in 1881 and his son Herbert was born there eight years later. In 1894, the elder Tullgren headed to South Dakota as a prospector in search of gold. While out west he also worked at Storm Cloud Mining in Prescott, Arizona.

By 1900, the Tullgrens, however, were back in Chicago where Martin went into partnership with Archie Hood, opening Hood & Tullgren Architects, moving the firm, a few years later, to Milwaukee.

After attending military school in Virginia, Herbert returned to Milwaukee in 1908 and joined his father’s firm as a draughtsman. Two years later, the Tullgrens left Hood behind and launched Tullgren & Sons. When the father died in 1922, Herbert took his place at the top.

A family real estate business, called the Terra Company, started in 1923 and was helmed by Minart. Four years on they Herbert W. & S. Minard Tullgren, Inc. real estate company, but the following year, Minart died and his wife stepped into his role.

Later, Herbert joined other important Milwaukee architects in designing the Parklawn Housing Project, for the Housing Authority of the City of Milwaukee. He died in 1944.

A little site history

In order to build its new home, Milwaukee Western Fuel had to first tear down an existing building on the site.

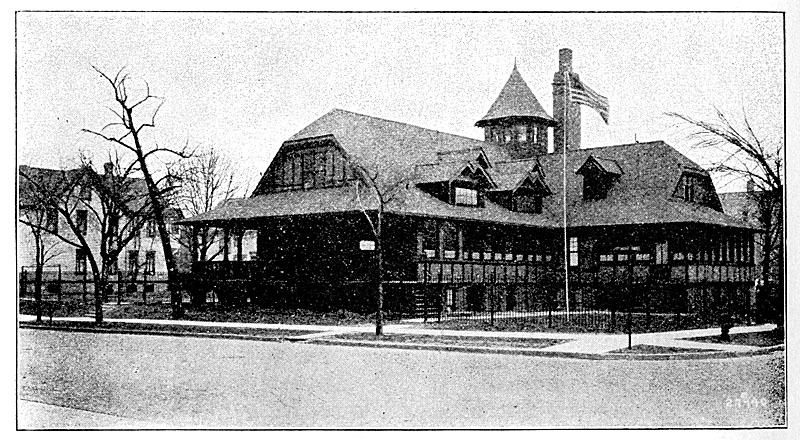

That quirky structure, which looked not unlike a Black Forest country retreat was actually built as a hospital in 1894 by Dr. Horace Manchester Brown, who opened a facility bearing his name in the wood-frame structure with its jerkinhead gables and a peaked tower on top.

According to a great post on that building (from whence the above photo came) by Yance Marti, "inside was modern for the time and cost $18,000 to build. What made it unique was the fact that it was the first strictly non-sectarian hospital in the city."

Later, it was called Lakeside Hospital.

"In 1915, Ford Motor Company bought the property across the street and began plans to build a large automobile plant there," Marti wrote. "Dr. Brown pushed hard against the proposed plant and filed a lawsuit which he didn’t win but the furor led to stricter zoning laws preventing manufacturing from being built that close to a residential district. Shortly after the factory opened Dr. Brown closed the hospital. In a strange twist of fate the factory was taken by the federal government late in 1918 to be used for a medical hospital during the war."

In 1919, the Country Day School – which had been started two years earlier – purchased the shuttered hospital for use as a "Junior School." In 1931, it opened a "Play School for Children ages 3 to 6." The school (which merged with two other schools in 1964 to become University School of Milwaukee) closed soon after.

Out with the old ...

The changes at the site happened rapidly.

News that the old building would come down was reported in the first days of 1934. A report in early February included a rendering of the new building and an update that the former hospital and school was at that moment being demolished.

A building permit for the new structure was issued in April and by the end of that month, excavation was already underway. By early June, the columns of the concrete skeleton were being poured and by early September, workers were already inside plastering. Finishing work was wrapping up by the start of November and at the dawn of December, Milwaukee-Western Fuel Company had already moved in and was featuring its new building in advertisements.

Though I haven’t found interior photos, Sean Phelan, who owns the building today, tells me he’s seen one of the main floor and that it looked like a bank, with a row of teller-like windows where customers would come to, presumably, order and pay for fuel deliveries.

The building appears to have served this purpose until the mid-1960s – even after a merger that led to a new name, Northwestern-Hanna Fuel Company. For most of the remainder of the decade, the building was occupied by UW-Milwaukee’s Publications and Duplication Department.

The St. Mary’s Guild women’s group occupied the second floor and in the early 1970s, the Antiques Ltd. shop relocated from its Downer Avenue home to the first floor. For the remainder of the 20th century, the building was occupied by a variety of office tenants.

Modern times

In 2004, Izumi’s Japanese restaurant moved from its intimate space in a former gas station next door – occupied by Seoul, a Korean restaurant, ever since – creating a lovely restaurant on the first floor and for many of us, the building is best described as "the Izumi’s building."

Just about a year ago, Izumi's owner Fujiko Yamauchi announced the restaurant would close and it is now occupied by a second Kanpai location.

In about 2011, OnMilwaukee toured the building when seeking new office space and despite the fact that I called dibs on a spot up there with a view I liked, we moved Downtown instead. Now, the upstairs is home to Work Lofts, a co-working office and meeting facility.

Before a tour through the basement, where we stop to check out a dumb waiter that was used to send cash down from the main floor to the basement, where there were a number of vaults, including a huge, room-sized one that’s still there, Phelan shows me Work Lofts.

"We purchased the building almost three years to the date, and purchased it because if it's location on the East Side," says Phelan. "At the time, the second floor was vacant. About a year and a half ago I started looking at how we could reignite the space, and really make it more of a community as opposed to these little individual silo offices."

Phelan tapped The Kubala Washako Architects’ Chris Socha and a design team that works with Colectivo to reimagine and reconfigure the space.

The result is a bright and welcoming array of areas that feel as much like a cafe as an office. There are private offices that tenants can rent for themselves, a group office in which tenants can rent a workspace, a fully loaded kitchen, a technologically up to date conference room, small workspaces that conjure phone booths of old, seating out in the main area and a lounge with a beer tap, a cold brew tap, an ultra-modern coffee-making system, snacks, tables and more.

Though the upstairs is extremely modern, Phelan wanted to make sure the building’s Art Deco exterior appearance was represented inside.

"We wanted to really make sure that we were respectful of the Art Deco, Art Moderne architecture of the building, but at the same time, we didn't want to make it look like Disney Land, completely Art Deco," he says. "So we took colors, and we took some of the forms of the outside of the building."

So, those earth tones you see outside, feature heavily inside Work Lofts, but so does one of the terra cotta panels. That stoker shoveling coal into a furnace is outlined on the window of the conference room right inside the main entrance to the space.

"We wanted to create an environment that people felt comfortable in, and they could be productive, and they could work and not necessarily be distracted with all sorts of different things," Phelan says. "It's really fostered a connection for people. People come in the morning and they'll say, ‘Hey, do you want some coffee? I'm about to make some.’ And that fosters a conversation.

"People recognize everybody in the space. It's not a transient group. And it really, truly becomes a community."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.