Unless you’ve been comatose or live in a cave, you no doubt are very much aware that this is Summerfest’s 50th year of operation. For many people around the festival in its earliest days, though, this year is also remembered as the 45th anniversary of perhaps its most notable event.

The first few years of Summerfest were much different than now. Following then-Mayor Henry Maier’s vision, the fest was really a series of small entertainment events spread out across locations throughout the city, including at County Stadium.

The diffusion of these events made it difficult for the public to keep track of what was going on where. Couldn’t check the website or follow along on social media. So, by 1972, Summerfest had been consolidated at the abandoned Nike missile site along Milwaukee’s Lakefront, which became its permanent home.

Back then, the grounds in no way resembled the sophisticated venue we see today. The stages were wooden platforms under rented tents. The makeshift backstage areas were hammered together from sheets of plywood. At best attendees sat on flat wooden benches – many, if not most, preferred the ground.

The Main Stage, such as it was, rested approximately in the space taken up now by the Johnson Controls World Sound Stage. Performers were generally delivered to it by boat.

On July 21, 1972, George Carlin was one of them.

The son of Irish immigrants, Catholic school-educated Carlin, then 35 years old, was very much a known quantity. He had been one of the most frequent guest hosts on Jack Paar’s "The Tonight Show." He was also present when Lenny Bruce was arrested for obscenity in Chicago and was thrown into the police wagon with him for refusing to show the cops his identification.

But while he admired Bruce’s style of obscene comedy and political commentary, on TV, he catered to mainstream audiences. So, by the late 1960s, he was very wealthy, to the point of having his own private jet.

Then, partly at the urging of his RCA Records manager, he began to abandon his slicked-hair, suit-and-tie persona of TV fame in order to appeal to a younger audience. He took on a laid-back, long-haired, counter-cultural look – jeans, T-shirts and an earring. And his routines shifted to mocking the very TV shows that had made him rich and famous, laced with obscenities and sexual vulgarity.

Jeff Abraham, who represented Carlin in his later years, recalls Carlin telling him, "Look, I was 30 years old on TV entertaining audiences who were 10, 20 years or more older than me. I knew I couldn’t sustain it." Carlin feared in a few years he’d end up entertaining lounge lizards in the Catskills.

The transformation was not without cost, at least initially. His bookings dropped dramatically, reportedly by as much as 90 percent. He became "too hot to handle." By the time he stepped onto the dock at Summerfest, he was a much cheaper date than a few years earlier.

As part of his critique of the media, he had recently developed a "Seven Dirty Words You Can’t Use on Television" routine, which was recorded on a new album, "Class Clown." (OK, it was actually six, one being a derivative of another. But who’s counting?) Since the album had not yet been released, it’s doubtful that Charlie Fain, then Summerfest’s entertainment director, was aware of it when he booked Carlin for the Main Stage that evening.

The lineup for the evening was clearly aimed at a young audience: Carlin was preceded by Brewer & Shipley, followed by Arlo Guthrie. But there were also many families in the crowd of about 35,000 that included children – not the least of which was Carlin’s own wife, Brenda, and 9-year-old daughter, Kelly.

Apparently some parents were expecting to see the former G-rated Carlin from his "Tonight Show" days. That Carlin had left the room.

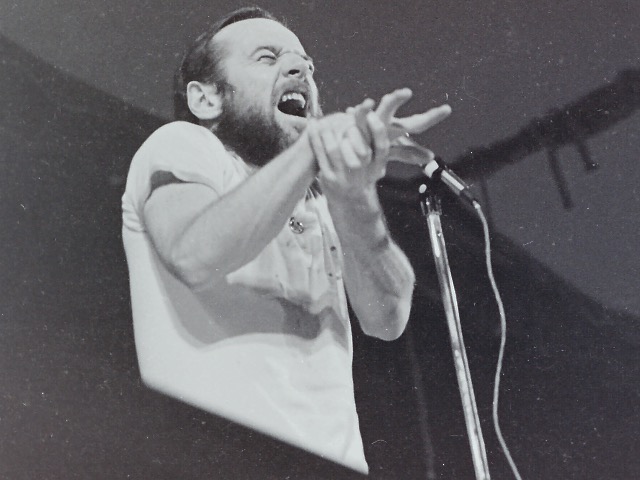

Carlin began his act close to sunset, past most little kiddies’ bedtime, at first in a fairly tame manner – political satire, attacks on the War in Vietnam and the occasional joke using mild vulgarities. Overall, everyone seemed pleased.

Then he launched into his "Seven Dirty Words" shtick. He said them once. Then again. Quite a few people found it very funny. If the children reacted, it wasn’t immediately obvious. But some in the crowd were clearly not amused.

That included one Elmer Lenz, an off-duty Milwaukee police officer, who apparently had never heard of, or paid any attention to, the many court decisions that allowed performers to say anything they wanted on stage under the First Amendment protection. One such decision had involved Lenny Bruce.

Lenz was at Summerfest with his wife and young child, but became incensed at Carlin’s language and went to a pay phone to call in the troops. He wanted Carlin arrested for obscenity.

"We were sitting near Lenz," said Lois Hoiem – then Lois Reitman, "and suddenly he stands up and shouts, 'Who does that son-of-a-bitch think he is using language like that?'" You could argue that the phrase SOB probably couldn’t be used on TV then, either.

Contrary to common belief, Carlin was not hauled off the stage. He continued his performance to its regular end. But meanwhile the police were gathering, ready for him backstage.

"The cops there were enraged with Carlin," recalls DJ Bob Reitman, who emceed the show. "They were using a lot of those seven dirty words to describe him. They couldn’t wait to get their hands on him."

Also waiting to get his hands on him was Charlie Fain, but for a very different reason. Carlin’s love of cocaine was widely known in the entertainment industry. Fain was less concerned about the obscenity arrest than what might be found in Carlin’s pockets when he arrived for booking at the police station.

In Kelly Carlin’s later-published family memoir, "A Carlin Home Companion," she writes that her father was holding both pot and coke while onstage. Kelly’s writings also reported that her mother had pulled a bag of drugs out of her purse and stashed it inside a bass drum.

As Carlin continued his act on stage, his wife suddenly appeared, pretending to bring him a glass of water. Carlin was taken aback until she whispered that the cops were getting ready to arrest him. Finally, as he wrapped up his act and stepped away from the mike, Fain and an assistant took him by the arm and managed to spirit him briefly into Fain’s office. It bought them a few minutes of precious time before the cops came knocking.

While only Carlin and Fain were inside, it didn’t take much imagination to figure out what was going on.

"Let’s just say it’s possible Carlin left Charlie’s office a gram or two lighter," said a former Summerfest stagehand on the scene who prefers not to be identified. "Fain’s quick thinking probably kept this from becoming a much bigger problem for both Carlin and Summerfest."

While Officer Lenz might not have known much about free speech protection, the Milwaukee City Attorney did. Accordingly, he had Carlin charged with the catch-all "disorderly conduct," which can mean just about anything a prosecutor wants it to mean. Carlin was booked and released on $150 bail that same night.

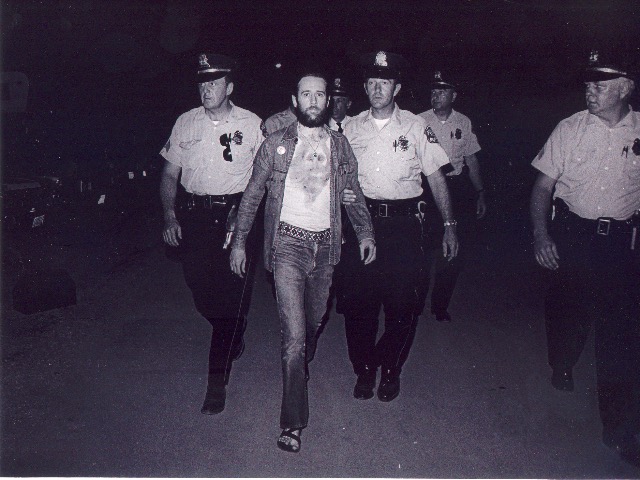

By the end of the next day, newspapers all over the country had published a photo of Carlin being led away by two doughy, bored-looking Milwaukee cops, with him staring dead-on at the camera with a dazed "WTF" expression on his face that spoke volumes.

There’s long been a saying in public relations: "I don’t care what you say about me as long as you spell my name right." One name that was spelled right in the captions under the photo was "Summerfest."

Previously unknown much outside southeastern Wisconsin, Summerfest was suddenly thrust into the national spotlight. No one knew what it was, except that George Carlin had been performing there. So it had to be something, right?

Presumably Carlin’s arrest was not exactly the kind of exposure former Packers defensive tackle Henry Jordan had hoped for when he became the festival’s executive director two years earlier. But, hey, the word Summerfest was now being uttered by radio and TV commentators nationwide.

Nonetheless Jordan defended the police actions, saying that booking Carlin was "the first mistake Summerfest ever made." Those of us who attended the Sly Stone Summerfest appearance in 1970, which required riot-helmeted police to keep order, might argue the point.

The case didn’t last long. After a few delays, it was heard that December in Milwaukee Municipal Court. Carlin didn’t show up but sent along a copy of "Class Clown" as his "defense." Judge Raymond Gieringer listened to it, laughing periodically along with others in the courtroom and dismissed the charges.

Whether the arrest notoriety helped Summerfest remains a matter of debate. But it sure didn’t hurt Carlin’s career. He was soon back in demand by the mainstream media, which was itself starting to look more counter-cultural all the time. He began referring to his routine as "The Milwaukee Seven" in follow-up national television appearances, even thanking Judge Gieringer by name.

In 1975, Carlin hosted the first broadcast of "Saturday Night Live" and was a regular in many sketches on subsequent shows. He even wrote a book on his experiences there, "Backstage at Saturday Night Live." He had his own HBO comedy special two years later and, in 2001, was given a Lifetime Achievement Award in comedy. And over time, his "seven words" started creeping onto TV dramas – you can hear them all these days, particularly on cable channels.

But as time went on, he also started coming off the rails. He was booed onstage in Las Vegas on 9/11 for making jokes about people who had been killed in the terrorist attack that day. He was eventually banned from Sin City altogether for telling his audience at the MGM Grand they were "morons" for coming there to gamble.

Eventually Carlin’s longtime drug use caught up with him, and he entered treatment for Vicodin addiction. At his final appearance in Milwaukee at Potawatomi Hotel & Casino in 2007, he was disheveled and disorganized, apologizing to the audience for having to read material from index cards he shuffled through his hands.

When Carlin died the next year, the New York Times published a lengthy obit, recounting his many achievements as a TV host and comedian. But in their print edition, they ran only one photo of him: Under arrest in Milwaukee, 1972.

(Note: Despite extensive efforts, we were unable to contact either Fain or Ron DeBlasio, Carlin’s manager at the time, for comments. Henry Jordan died in 1977.)