If news that Nomad World Pub owner Mike Eitel had sold the building the bar’s occupied since 1995 gave you a little scare, don’t worry. Eitel says he’s not going anywhere.

In fact, he’s beginning to take note of the fact that next year will mark the popular Brady Street corner tap’s 25th anniversary at 1401 E. Brady St.

"I guess I’d better start planning that," he says with a laugh as we sit in a booth in the Nomad’s upstairs bar, which used to be an apartment where Eitel lived when he, unexpectedly, found himself in the bar business.

On a brief stint back in Milwaukee from Thailand, where he was studying, Eitel was approached by Julilly Kohler, who had bought the bar and wanted to use it to launch a Brady Street revival.

"I hadn't lived here and really had no intention of living here ever again," Eitel remembers, "but Brady Street was the one spot where there was cultural diversity, socioeconomic diversity. "My parents lived in Cedarburg and I was kind of homeless, looking for a job."

When Kohler told Eitel she was buying the place and wanted him to be the tenant, he considered it, but they initially had divergent ideas about the place.

"I was like, '’Yeah, great, I know a ton of people in Nepal and India and Thailand. I could do an import store.’ And she was like, ‘'No, it has to be a bar.’ I said, ‘'I don't drink, I don't smoke, I don't know anything about business, there's no way I'm doing that.’

"But then I had been a carpenter and a mason’s laborer and a kind of jack of all trades back then so she hired me to start for an hourly wage gutting some of her other properties, and when we were in here I just kind of fell in love with the idea of restoring it."

The first photos in the stack of photo albums the Nomad has in its basement attests to the fact that the place was a mess. But it had a long history that Eitel could sense and it drew him in.

A little history

The earliest references I can find to The Nomad building date to 1892, when it appears that real estate man P. Henry Reilly pulled a permit to raze an earlier building the site.

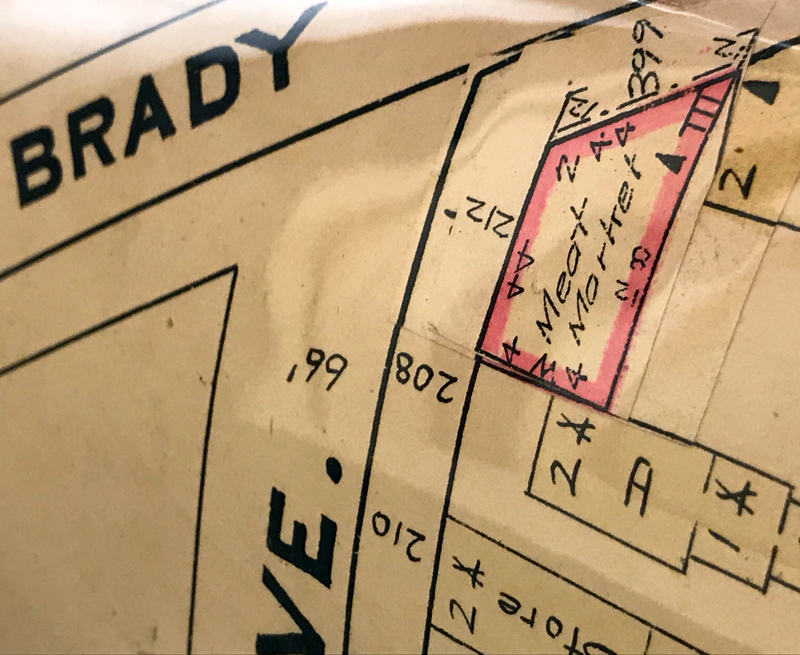

While the 1888 Rascher’s map shows the current building on the site, that map was updated and it’s clear that the Nomad site was part of that update, its outline pasted over what had previously been shown.

The building is noted on the map as a "meat market" and that would fit with documentation that suggests one of its earliest tenants was Eli Bierman, a grocer who got his start as a peddler on Water Street in the 1880s before moving up to Brady Street, where he occupied the two-story shop at Brady and Warren that Reilly built in 1892 at a cost of $300.

By 1895, the building appears to have been owned by a John Donohue, who spent $500 elevating it two feet and adding new sills. But, Bierman continued to operate his dry goods and grocery there, along with his wife Mary, until about 1899.

That's when the first saloon opened, run by James Doyle, who previously operated the tavern on the corner of Farwell and Brady (which you likely remember was, until recently, a Starbucks).

Doyle remained there until 25-year-old Frank Lang took over in 1902 and began a long run, remaining behind the bar until the onset of Prohibition.

During his nearly two decades there, Lang – the Wisconsin-born son of German immigrants – had his ups and downs. Two years in, for example, he accidentally shot his mother. Definitely a down.

"Frank Lang, who runs a saloon at Warren Avenue and Brady Street," wrote the Milwaukee Journal in 1904, "swore out a warrant against a number of young men for assault. At a row in his place one of them struck him over the head with a billiard cue. He drew his pistol and fired just as his mother entered the back door. She received the ball in the arm, but is recovering."

A few years later, Lang’s 23-year-old wife Cecilia gave birth to a son there. (Surely an up.)

As with many taverns, Lang’s was a gathering place for more than just drinking. There was entertainment and there was politics.

In 1916, wrote a newspaper, about 200 were on hand at Lang’s on a Monday night, "to hear voters in the First Ward indorse (sic) the candidacy of Albert Trzebiatowski for alderman."

Two years later, a pair of detectives walked up to the flat above the bar and arrested 21 men, "on charges of being inmates of an alleged gambling house. John Ebert, 42 years old, is charged with being the keeper."

By the time the Volstead Act went into effect in January 1920, Lang appears to have left to open a restaurant across Brady Street, and was replaced by Joseph Lujeski (some sources call him Stanley Lojeski, others Joseph Myszewski), who wasted no time getting himself in trouble.

In August, according to the Sentinel, "Sgt. Arthur Luehman led a squad consisting of Patrolmen Heling, Howitt and Ballsieper into a saloon at 365 Brady Street early Sunday morning. Joseph Myszewski, 22 years old, was arrested as keeper of a disorderly house, and 12 others, including one woman, were arrested charged with being inmates. The young woman, who was found hiding on the second floor, according to police, gave her name as Mary Wisocka."

The next day, the paper added that, "a large quantity of moonshine, whisky and wines were found."

Perhaps it’s no surprise that Stanley Joe Lujeski Lojeski Myszewski didn’t last long behind the bar.

The Latona era

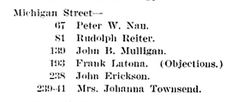

By the end of 1920, Frank Latona, a Sicilian immigrant who had briefly been slinging drinks on Michigan Street in the Third Ward, moved in and stayed for about a dozen years.

Born in Bagheria in 1879 – according to an impressively in-depth blog post penned by his granddaughter Vicki Wilson – La Tona (which is how his name appeared on his birth certificate, though it appears to have elided later into Latona) arrived in Milwaukee, where his brother Salvatore was already living on Jefferson Street in 1904.

In the following years, he worked as a teamster and a garbage man, and married widow Maria Catalano, who already had a daughter, Francis. In 1920, with Prohibition in force, Latona, then 40, began running the "soft drink parlor" on Michigan Street.

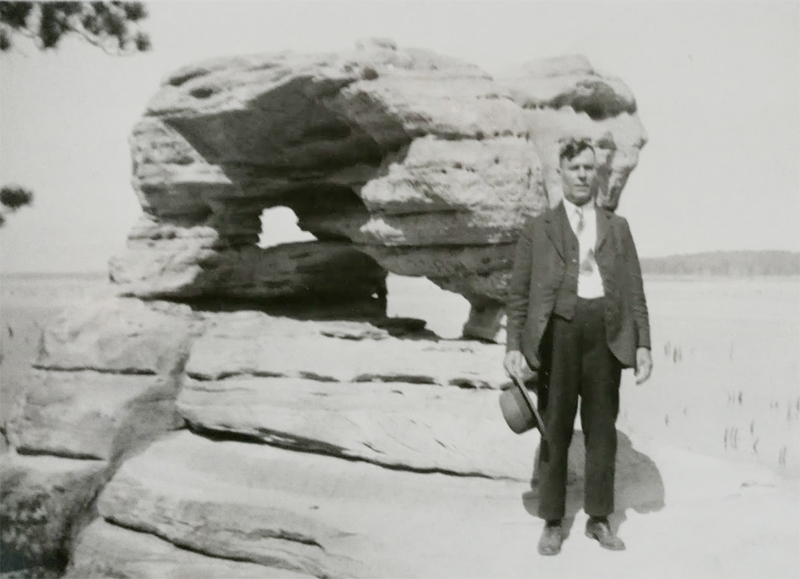

Frank Latona at the Wisconsin Dells in July 1930. (PHOTO: Courtesy of Vicki Wilson)

He wouldn't remain there long. His permit request was heard by the Common Council in June and by October he had requested and been granted permission to operate at 365 Brady instead.

Though there were apparently some objections to Latona's first permit, those have not turned up in newspapers of the day. But Latona did make the papers on one occasion.

In 1923, according to the Journal, Latona filed a lawsuit against Leo Fricano on behalf of his 16-year-old stepdaughter. Frances Loschiavo claimed that Fricano promised to marry her, "at various times in 1921 and 1922." When Fricano failed to follow through, the suit was brought, seeking $10,000 as a "heart balm."

The article, Wilson added in her post, "doesn't mention that Leo fathered her son, Joseph, born in November of 1922."

Fricano, who later did get married – in 1929, to Emilio Torra – also worked at the tavern, it seems. According to Wilson, "My oldest aunt – Frank's step-daughter born in 1907 – would go in the bathroom when investigators would come around and then come out with her hair damp, saying she was taking a bath. In reality she was pouring the gin down the tub."

Though Latona still owned the place into the 1930s, he appears to have leased it periodically to other operators. For example, in 1922, the saloonkeeper James Cavanaugh wanted to leave and asked to have his license transferred to a place on Clybourn Street that had been run by Henry Hopp.

The Sentinel noted that, Cavanaugh’s "request was kept in abeyance until he presents an affidavit to the police dept that he is not asking the transfer for Hopp, which the police charge he attempted to do."

Hopp, it seems, was busted by prohibition officers on the very night of the day on which he was granted a license to operate.

Cavanaugh, however, claimed he bought the place and was going to run it himself.

During 1927-28, Latona let the place to Carl Stornowski, and then Philip Balistrieri during 1927-28, but seems to have returned by 1930 and stayed on until 1933, the year Prohibition was repealed.

From 1934 to ‘36, he rented the saloon to Joseph Peplinski (pictured at right, in an image courtesy of Kay Kenealy), before selling it to Majestic Realty and moving out to Wauwatosa. Latona died in 1946, at the age of 67.

Majestic rented it to Richard Berger for about a year, then Casimir "Harry" Zielinski – who dubbed it Warren Cafe – for three years.

In 1941, Eddie Carroll moved in and operated Carroll’s Tavern there until his death a few years later, upon which his wife Neta kept it going until 1954, when Sylvester Nolde began a really long stretch.

Interestingly, on and off over the years, and long after Repeal prevented breweries from owning tied houses, Schlitz was listed in some documents as the owner of the bar. So, I asked encyclopedic Milwaukee brewing historian Leonard Jurgensen.

"There is a fine line with regard to brewery ownership and control of taverns with the repeal of prohibition," he told me. "Ownership of tavern properties was permitted as long as they weren’t controlled by the brewery and didn’t sell beer.

"As per my records and real estate holdings of the Schlitz Brewing Company of Milwaukee, the saloon property at the corner of Warren & Brady was sold by the Schlitz to a private individual in 1925 (likely Latona) for $8,550. It was very common for the brewery to sell their saloon properties under the terms of a land contract. In some cases, those mortgages/notes (land contracts) were defaulted upon, the property was reclaimed by the brewery and resold. It is also possible that the brewery took out and paid for the permits and the renovations of that property in order to keep that wholesale (Schlitz Beer) account."

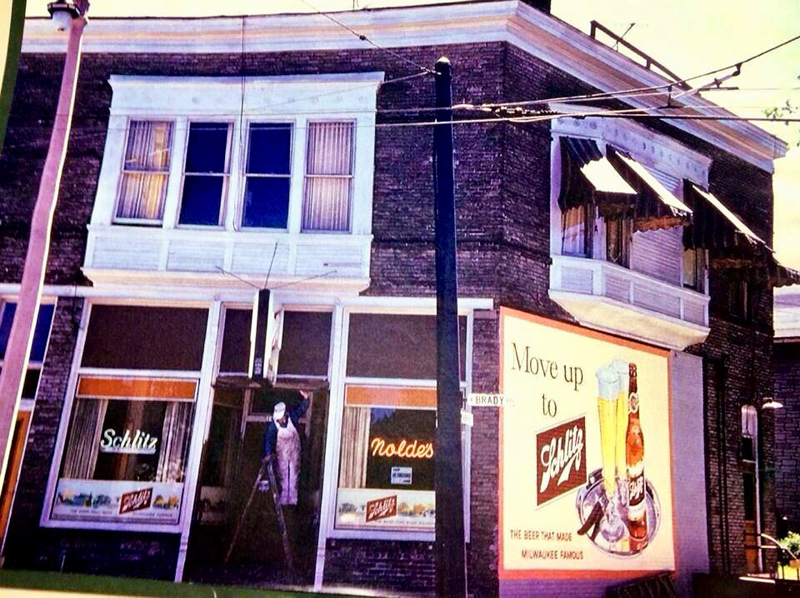

The Nolde’s era

The last Schlitz reference I found was in 1961, by which time Nolde had been operating for about six years. During that period, in 1957, Nolde found himself behind bars, but with the Common Council coming to his defense.

Nolde's Tavern. (PHOTO: Unknown. Courtesy of Adam Levin)

In 1957, 27-year-old Irving Sisk, angry at having lost at pinball, flung an ashtray at the machine, breaking it. He then left, went over to Emil Miller’s bar at 1731 N. Arlington Pl., and did the exact same thing. Miller called the cops.

When the police arrived, they didn’t arrest Sisk, who they found hiding under a car about a block away, but rather 47-year-old Nolde, who they charged with making payouts to pinball winners.

According to the Journal, Sisk, "said he lost $100 in the last two months on the machines and said Nolde paid him $50-$65 in winnings in February. Nolde denied making payoffs but admitted his machine was set up for free games, illegal under state law."

Nolde was fined $50, but when the Common Council considered revoking Nolde’s license on recommendation of the police chief, the aldermen seemed incensed, calling the evidence "flimsy."

"‘You mean this man was convicted in the district court on the testimony of a man who threw the ashtray?’ asked Ald. Vincent Schmit incredulously," the paper reported.

Ald. Alfred Hass of 3rd district added, "This is a rather unusual case. A man who tried to cooperate with the police department ... calls them and instead he gets slapped with a $50 fine."

Thirteenth district Ald. Bernard Kroenke said, "I can’t understand why Sisk wasn’t prosecuted."

Afterward, Nolde appeared to have avoided trouble.

In 1971, he’s the one who closed up the windows and covered them with rustic cedar.

Five years later, the afternoon paper recounted, "Two alert bartenders caused the arrest of a 31-year-old holdup man early Monday."

A man entered Nolde’s and opened his coat to show bartender Curtis Leffingwell he had a gun. The robber took $152 from the register and threw Leffingwell a $10 bill as a tip for not alerting police, though he called anyway.

When they arrived, Leffingwell told police the gunman had gone over to Shenanigan’s, at 1701 N. Arlington Pl. There, police found, the crook had pointed the gun at 33-year-old bartender Peter Stypudt, who, after distracting him, smashed him over the head with a wine bottle.

As four customers held the crook down, his gun accidentally went off, giving him a powder burn.

Perhaps this is the sort of thing that led Nolde to get out of the tavern game after more than 30 years, and in 1978 he rented the place to Joe Armato, who opened Brady Street Bunch and operated it until 1989 when Thomas Van Dusen opened Breeze’s On Brady.

The Nomad pitches camp

Breeze’s closed in 1994, when Brady Street wasn’t exactly the place it is today.

"Brady Street was a different animal," says Eitel. "We had prostitution and drug dealing on the corner."

Right from the start, Eitel was committed to making that disappear.

"That photo of us standing there (before the bar even opened, see below), a guy came in then and started using the payphone at the back door for a drug deal," Eitel recalls. "So the next day I ripped out the payphone."

Mike Eitel (left) and friends, before the opening of the Nomad.

(PHOTO: Unknown. Courtesy of Mike Eitel)

Then Eitel opened up the windows that Nolde had planked over in the early ‘70s. "I wanted to open everything up, instead of (having) a hideaway.

"When I first got here with the crime across the street, I was talking to Mike D’Amato who was our alderman at the time, and I said it's insane that this city doesn't allow outdoor seating on sidewalks even if you don't sell food. If you want to get rid of the heroin and the crack and prostitution and all the stuff that's going on on the corner put some eyeballs right there staring at them all day.

"That's how the Nomad beach (the informal name for the outdoor seating) started. We were the first people to get that sidewalk seating and that completely transformed the neighborhood overnight. There was still all kinds of crap going on in the neighborhood but at least this corner changed forever. We put four people out there drinking Guinness, staring at somebody trying to make a drug deal and, surprise, the dealers went somewhere else."

Using a $10,000 loan and a bartop found in an alley behind the former Island Restaurant down the block, Eitel whipped the place into shape.

Before the opening of the Nomad. (PHOTOS: Unknown. Courtesy of Mike Eitel)

He demolished the bar along the west wall and found evidence that the original bar had been where he wanted to put his reconditioned bar, along the east wall.

To help raise money, Eitel enlisted his father, who had just retired from his day job and opened a pottery studio in Cedarburg, to make steins for a stein club. Hawking those to his friends, he raised more cash.

The Nomad World Pub opened on St. Patrick’s Day 1995 with a performance by Milwaukee Irish folk outfit The Ghillies.

The Ghillies on opening night. (PHOTO: Unknown. Courtesy of Mike Eitel)

"The timing was good," he says. "We opened on Brady Street Saint Patty's weekend and Irish music was starting making a comeback. I had The Ghillies here and I invited anybody and everybody I knew. We had a line out the door and it was pissing rain and sleet."

The turnout was so good that the bar ran out of beer.

"The next day I had to drive my pickup truck out to the warehouse because they didn't know who the hell I was, so they weren't going to come give a special delivery to some idiot opening a bar on Brady Street.

The opening night crowd. (PHOTO: Unknown. Courtesy of Mike Eitel)

"My brother had flown in from California, he was a carpenter, too. The two of us had to build a wall down the middle of the basement because that night, everybody was jumping up and down. Our brand new ductwork split apart, my back bar ... we were just literally holding the thing up because the floor was, I think it’s called deflecting substantially."

Over time there have been more changes. Eitel added the staircase and transformed the old apartment upstairs into another bar in time for the 2014 World Cup.

He demolished a back house next door and created the patio, too.

When you enter the Nomad, it still feels like a classic Milwaukee bar, with its hardwood floors, and, best of all, the sink outside the bathrooms at the back.

And the place has always been a scene – that hasn’t changed. Paging through those photo albums, Eitel and I come across page after page of notable Milwaukee musicians, scenesters, bartenders and more than one Nomad bartender who later went on to open a place of their own.

Bands have played there to packed rooms, DJs have spun records in sweaty late-night sessions, regulars have come and gone, others have come and stayed.

"It’s amazing how many of these people are still coming here," Eitel says as he marvels over the nearly quarter-century old photographs in the albums on the table in front of us.

The once-reluctant Eitel, who later helped grow the Lowlands Group food and beverage empire, now has big ideas – there’s another Nomad in Madison, and he operates bars and other businesses in Milwaukee and Delafield – and he plans to slow down a little and work toward making them reality.

"I think our plan this year is to just operate for sanity purposes," he muses. "Because last year we opened three things, held a 31-day festival. It almost killed me and my entire staff and my family. So we're going to really drill down this year and then the plan is to grow the Nomad brand in a different market.

"Even before I was doing Trocadero and Hi-Hat and all that stuff, the plan was always everywhere I traveled in the world needed a Nomad. I was like, ‘I’ve gotta go put Nomads out there.’ And I still never have. I think I'm looking to do that finally. At the time, there was no way I can have done all those.

Now, he’s got his eyes on Chicago, Atlanta, Detroit and Toronto, and selling the Nomad building is all part of the longer-term vision.

"I don't need to be a landlord," says Eitel, "and I did need to strengthen the company and get us ready for growth."

As for Nomads in Thailand and Nepal?

"Over there, there'd be my jalopy-style version of the Nomad. When all of our blended family kids are out of the house, then we'll really start looking at more of where we connect cities in the Midwest to wherever it is I want to live.

"I'd like to die on a beach. Somewhere where I can actually do the polar plunge on New Year's Day and have the water be 80 degrees. That's the dream for my 60s, sort of like beachy, crappy Nomad vibes in authentic places. I’ve got nine years to get it done."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.