Many biopics have the habit of ignoring or gently brushing over the more unpleasant or complicated subplots of their chosen subject’s life. After all, many of these films are built to inspire – either audiences or, more likely, awards voters – and come with a stamp of approval from the subject’s family.

Bringing attention or focus to, say, domestic abuse ("Get On Up"), the complexities of sexuality and marriage ("A Beautiful Mind") or cold business tactics ("Jobs") merely gets in the way of those missions. As a result, cozier character arcs are chosen, a person’s relationships and complexities sanded down into something smoother.

After seeing the swooningly romantic, cue-the-inspiration trailer, I remember joking that I somehow doubted "The Theory of Everything" was going to address the fact that, in real life, scientific genius Stephen Hawking bailed on his wife for his nurse. That seemed like exactly the kind of complicated detail most biopics would reserve for viewers’ post-screening Wikipedia visits.

As it turns out, I couldn’t have been more wrong, as that’s actually the meat of "The Theory of Everything." It’s somewhat refreshing at first to see the movie attempt to take on that difficult aspect of the Hawkings' story. Unfortunately, that’s where the bravery ends. As the movie attempts put a pleasant glaze over an emotionally jagged situation, it becomes clear that there’s a reason why biopics tend to avoid these kind of complex emotional dilemmas: They’re not very good at handling them.

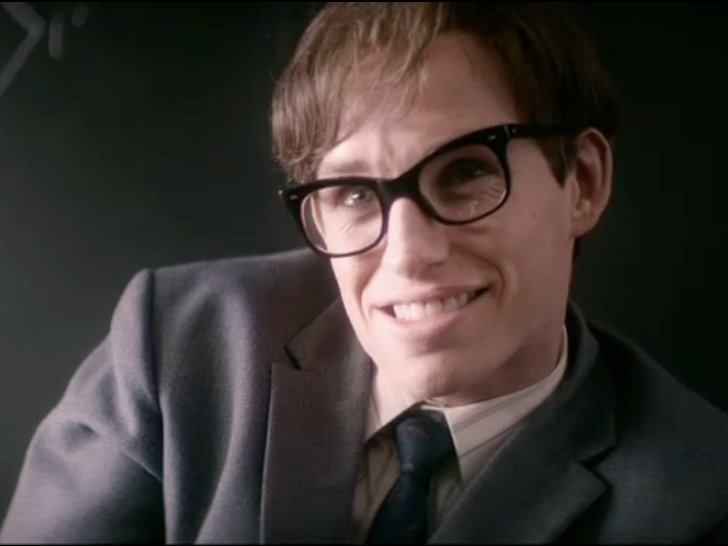

Then again, "The Theory of Everything" doesn’t exactly do the traditional biopic material all that well either. Eddie Redmayne (Marius in "Les Miserables") disappears into the role of Hawking, a gawky and awkward if lively young physics student at Cambridge during the ’60s. There, he meets Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones), and though the two come from very different backgrounds – he a staunch atheist physicist, she a religious arts student – they soon cutely fall in love.

Sadly, after a sudden stumble on campus, Stephen’s occasional twitchiness, gimpy walk and seemingly innocent clumsiness reveals to be signs of ALS. A doctor only gives him two years to live, his genius thoughts and ideas soon to be locked away, forever unknown inside his bodily prison. Stephen resigns himself to a life of solitude and soap operas, but Jane pushes him forward to fight through his debilitating ailment and prove his revolutionary work.

What that revolutionary work is, however, doesn’t seem to be of particular interest to "The Theory of Everything." Instead of diving into Hawking’s theories, director James Marsh and Anthony McCarten’s screenplay are more than happy to use cliché cinematic genius shorthand to get the job done: a montage of writing long equations at a blackboard, a scene of Stephen showing up to class with impossible questions answered and amazed glances from professors (played by David Thewlis) and peers (mainly his best friend, played by Brian Lloyd – who you may not recognize without his blonde hair and "golden crown" from season one of "Game of Thrones").

There are a few layman’s explanations for Stephen’s black hole and time theories mixed in, but for the most part, Hawking’s actual work and ideas – what he spent his life fighting his own physical limitations to share with the world – feel pushed off to the side as a nice detail. A viewer would be excused for walking out thinking Hawking was famous not for his scientific mind, but for simply surviving ALS and having a nice romance.

Then again, the first third of Marsh’s film doesn’t seem to have a sticking interest in much overall. The burgeoning romance is tender and sweet, and the performances are charming (Jones is particularly winning). However, the movie flowlessly rushes through the seemingly obligatory chapter, each scene feeling like merely a box to be marked off on its conventional biopic important events checklist.

Meanwhile, the inherent debate between science and religion gets a few conversational nods but is generally left malnourished. For a significant amount of time, it’s a question when "The Theory of Everything" will get to its story, rather than simply running through a list of biographical bulletpoints that received limited fleshing out.

Eventually, the movie does reach the meat of the story: Jane and Stephen’s slowly fading marriage (very different from the romance being sold in the ads, though "watch a marriage fall apart" probably isn’t the most marketable hook). As Stephen continues to defy his doctor’s original prognosis of two years, the marriage takes its toll on the devout, exhausted Jane. She evolves into something resembling more nurse than wife, and her pleas to an oblivious Stephen for hired aid are met with joking dismissals.

After some time, he finally caves, and the two welcome Jonathan (Charlie Cox), a kindly widowed church choir leader, into their family to help. He and Jane, however, begin to develop feelings for one another, much to Jane’s emotional confusion and the shaming disapproval of Stephen’s family. When Stephen loses his voice due to a pneumonia-induced tracheotomy, Jonathan is replaced by the flirty Elaine (Maxine Peake), who would eventually replace Jane as Stephen’s caretaker and then as his wife.

There’s intriguing dramatic potential in this story angle about the honest trials of their marriage, but Marsh and "The Theory of Everything" handle it awkwardly. The film is too cautious to face the raw actual conflict and emotions – the pain, the anger, the sadness – of the Hawkings’ situation. So instead of making anyone feel bad, it essentially tries to deliver the most charming and inspirational story of a man abandoning his now loveless marriage.

While Jane is increasingly met with disapproval and drab visual greys, Stephen and Elaine’s flirtatious interactions – such as her cheekily reading an issue of Penthouse with him – are portrayed as glowingly charming, accompanied by Johann Johannsson’s insistent score (from the opening scene of a simple bike ride, the music is all overwhelming triumph all the time). Stephen plays a robot for Elaine’s uproarious giggling; meanwhile, Jane is coldly left alone in the other room.

Late in the film, while reading an early transcript of "A Brief History of Time," Jane discovers Stephen is finally acknowledging God. "Are you going to let me have this moment?," she asks. He smiles … and then a few seconds later reveals he’s essentially replacing her with Elaine. In the end, the movie seems as oblivious to her long constant plight as Stephen is.

Back in 1999, the real life Jane Wilde Hawking wrote a tell-all, "Music to Move the Stars," that brutally chronicled their marriage’s collapse, calling him "a masterly puppeteer" and describing a fight with depression due to feeling trapped. The two have reconciled since, but even when interviewed in 2011 for her second memoir, "Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen" – an account softened by time and unsurprisingly the one the movie is based upon – Jane still couldn’t find herself able to say Elaine’s name, and the divorce is called "horrendously painful."

Here, the reconciliation part is felt, but the true emotional struggle strife for both parties – especially Jane – has been removed for audience comfort, cloaked in cozy inspirational nobility rather than messy, honest humanity. Not that the movie needs to be grim, but considering what it chooses as its focus, the film disappointingly nixes complexity for something safer, more happily conventional. Marsh and McCarten want to have it both ways, depicting a heart-warming heart-breaking collapse. They want the sensation of healing without having to deal with the wounds.

Even if the script is a bit of a shambles, "The Theory of Everything" isn't completely lacking in power. Alongside cinematographer Benoit Delhomme, Marsh’s misty, shallow focused visuals occasionally give off the cloying impression that if you don’t start crying from all the inspiration, the movie will do it for you. However, they're still warm, gorgeous and rich with purpose more often than not. For example, he uses a distorting wide angle lens when the doctor delivers his two-year diagnosis not just for show, but because the news is such a horrifying, reality-altering event for Stephen.

But really, most of the story's effectiveness comes directly from Redmayne and Jones. Redmayne utterly vanishes into the role of Stephen Hawking, so effortlessly that at the mid-movie mark, it’s easy to forget one is watching a performance. It’s not simply a matter of the physical performance either, though his slow evolution from small arm-bending twitches to gimping to Hawking’s current crumpled posture is remarkable. Redmayne makes sure the character is alive underneath his contortions, his eyes speaking volumes about his humiliations, his hurt and his still very active sense of humor.

While the less traditionally showy of the two roles, Jones is every bit Redmayne’s equal. During their meet-cute phase at Cambridge, she’s an absolutely breathy charmer. She's both timid and assertive, a combination that only grows as the film continues. Even though the movie may not fully recognize Jane’s struggle, her performance does, her delicate yet fierce determination weighted down and slowly distorting into frustration – especially in a scene where she cracks attempting to teach a mute Stephen how to use a talking board.

The two performances have received a ton of Oscar buzz since the film's premiere, and it will most likely continue into late February. They deserve all the praise, but more so, they deserve a better movie around them.

As much as it is a gigantic cliché to say that one has always had a passion for film, Matt Mueller has always had a passion for film. Whether it was bringing in the latest movie reviews for his first grade show-and-tell or writing film reviews for the St. Norbert College Times as a high school student, Matt is way too obsessed with movies for his own good.

When he's not writing about the latest blockbuster or talking much too glowingly about "Piranha 3D," Matt can probably be found watching literally any sport (minus cricket) or working at - get this - a local movie theater. Or watching a movie. Yeah, he's probably watching a movie.