Among the more delicious examples of adaptive reuse in Milwaukee is the Colectivo Lakefront Cafe, 1701 N. Lincoln Memorial Dr., where not only is the coffee hot and the food simple and delicious, but also the setting can’t be beat.

While I love the lakefront site, I love the building even more.

The cafe, which opened in 2002, is a great reuse of a beautiful old civic building, and a successful reuse at that.

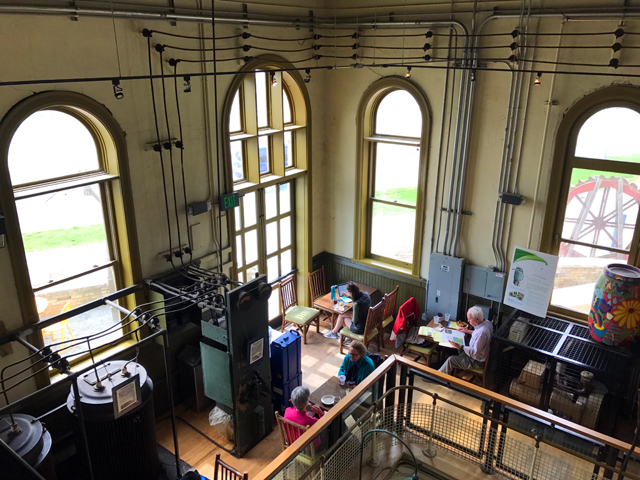

Though the building is a simple one-story, two-room shed, really, it’s an attractively appointed cream city brick one, executed in a Victorian Romanesque Revival style. The windows are arched, there are sandstone belt courses and, of course, that lovely cupola atop the hipped roof.

I like the cresting on either end of the roof, too. To me they look like something you’d see adorning the prow of an old sailing ship, hinting at the lakeside location.

Inside, the high ceiling is pretty eye-catching, and I like that there are little Easter eggs from the building's past to be found, too. Like this pipe jutting out from a wall...

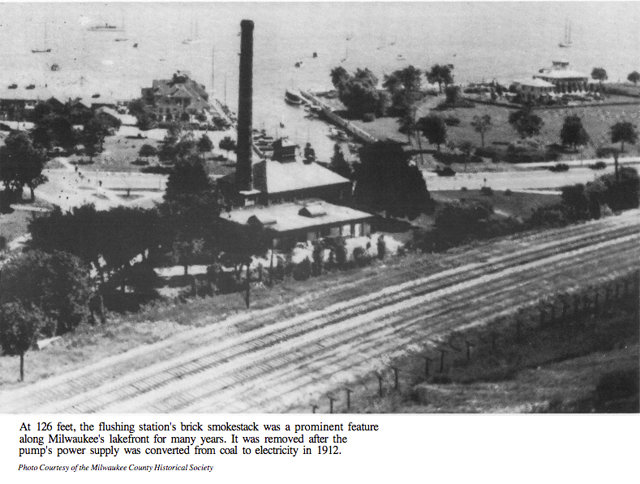

Alas, the architect of this 1888 gem is unknown. At the time, the city – which boasted a population of more than 200,000 – was more concerned with the equipment housed within the building and its function than with the building itself, which, notably, used to boast a soaring smokestack that has long since been demolished. Out back there was a low coal storage building, too, that is gone. You can see the chimney and that building in this photo:

The Milwaukee River Flushing Station was designed and built to do just what its name implies.

"When (this building) was built, the Downtown section of the Milwaukee River in 1888 was, as you might imagine, basically an open sewer," says Colectivo co-owner Lincoln Fowler. "In the summertime that stank, and in kind of classic 19th century brute force engineering, they said, 'What we need to do is flush that river.’

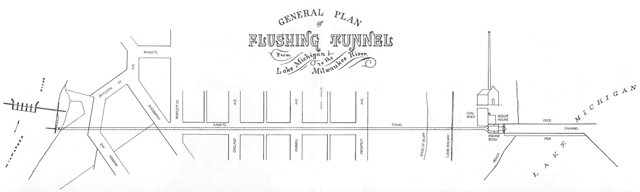

"So they dug a tunnel from basically right across the street here, under this building, which didn't exist at the time, and then it goes directly to the west and exits into the Milwaukee River immediately south of the North Avenue dam."

In 1887, the City of Milwaukee granted the largest contract in its history – $114,000 – to William Forrestal to build a brick-lined tunnel, 12 feet in diameter and 2,534 feet long from the site of the future flushing station, to the river.

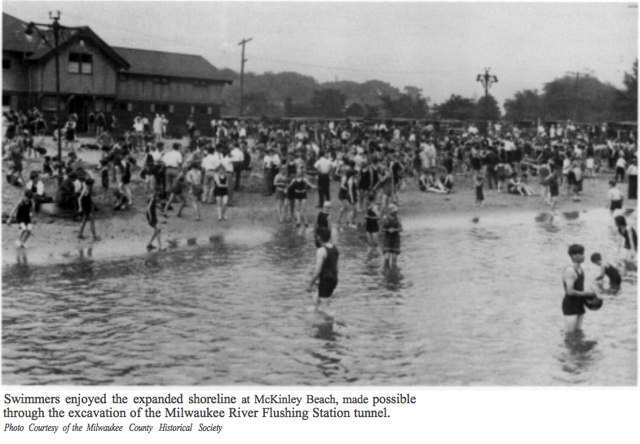

The earth that was removed was used as landfill along the Lake Michigan shoreline to create land where coal boats bringing coal to fuel the flushing station’s pumps could dock. It also helped create McKinley beach.

The tunnel, which still exists, runs under Kane Place to the river, where it opens into the river between Caesar’s Park and the North Avenue dam. Its creation was something of a herculean task, according to a Metropolitan Milwaukee Sewerage District history of the building.

"Cave-ins and foul air were a major problem and the length of the tunnel, combined with a diameter of only 12 feet, made working conditions difficult. Then, just one-third of the way through the project, Forrestal’s crew hit hardpan, or very dense soil conditions, that required the use of dynamite. Despite the obstacles, the work was completed in just eight months."

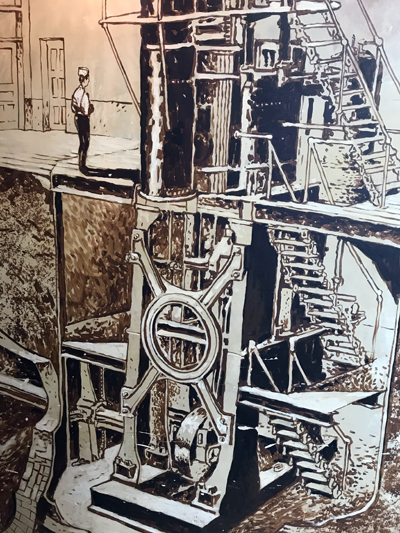

"There's a huge impeller, basically a huge fan blade, that is driven by a huge electric motor here," says Fowler. "It actually was the largest water pump in the world when it was built. It moved some enormous amount of water (525 million gallons a day), and that system still operates. It's never used, but it is functional. It's an amazing piece of equipment."

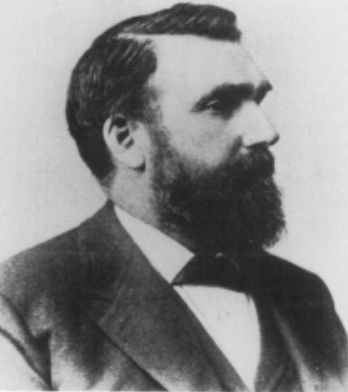

The plan for the "screw pump" system was the idea of Edwin Reynolds (pictured at left, in a photo courtesy of MMSD, as are all the old pictures here), an engineer working at E.P. Allis and Co., and was met with some skepticism among fellow engineers and politicians alike. One alderman vowed to "drink all the water that engine will throw."

The plan for the "screw pump" system was the idea of Edwin Reynolds (pictured at left, in a photo courtesy of MMSD, as are all the old pictures here), an engineer working at E.P. Allis and Co., and was met with some skepticism among fellow engineers and politicians alike. One alderman vowed to "drink all the water that engine will throw."

Considering the fact that when the system – and the pump house building – were completed in September 1888, it took a mere 13 minutes to get lake water into the river, and within a day, the river water had been cleared and the accompanying stench dissipated, that alderman likely had his fill of drinking water.

In that first 24-hour period, Reynolds’ pump – which would continue to operate into the final decade of the 20th century – basically replaced the entire volume of river water below the North Avenue Dam, according to that MMSD booklet.

Mayor Thomas Brown declared the system to be "the most important public improvement made since the building of the waterworks."

The building itself, as I say, is a simple one. One room houses the pump and the other – now the main room of the cafe – hosted the four boilers required to run it.

In 1912, the pump’s original steam engine was replaced with the 350-horsepower electric motor that was quickly ramped up to 450 horsepower and is still in place today.

In 1955, the city transferred ownership of the station to the Milwaukee Sewerage Commission.

"The ink was barely dry on the sale when the station’s long history of trouble-free

operation ran aground," notes the MMSD history. "Backflow from the river carried a giant tree stump into the pumphouse. When the wood hit the whirring impeller, two of its blades were damaged beyond repair.

"With its remaining two blades, the pump was put back in business, but its effectiveness was

greatly reduced. In 1985, the Sewerage Commission decided to restore the pump to its

original capacity. A new four-bladed impeller replaced the damaged one, and the pump was restored and automated."

In 1988, the exterior of the building was cleaned and its doors, windows and roof were replaced.

As late as 1992 the pump was still running from about May or June through October, a time when, according to a 1986-87 city Historic Preservation Study Report, "the dissolved oxygen in the river drops below two parts per million. This has ranged from two to five days per week and eight to 16 hours a day."

For many years, the building was also used for cold storage by the sewerage district. It was a lovely building but clearly a moribund one. There was no life around it.

And that is how Fowler and his partners – brother Ward, as well as Paul Miller – found the building at the dawn of the 21st century.

"I think it was actually Mayor Norquist that drove by this place and wondered why it wasn't being put to better use," recalls Fowler, "so the sewerage district put out a request for proposal and just to kind of illustrate the lack of interest, there were three proposals submitted: one by us, one by Starbucks and one by a roller skate rental outfit.

"If you go back then, you would remember (in the) back was just a kind of an unimproved gravel parking lot, and the building was used for cold storage of kind of random stuff for the sewerage district, so it was not an obvious retail location. It looks obvious from today's perspective, but back then it was definitely a question mark. You figured you'd probably do well in the summertime, but in the wintertime we felt like we’d be doing next to nothing."

But as you know if you visit the cafe, that’s not true. While it surely does a considerably more-booming business when the weather is warm, it is well-used during all seasons.

"I think part of the reason," posits Fowler, "is we took our work here very seriously. We’re sitting within the confines of Lake Park, we're working with a historic building. We needed to work to integrate this thing as well as we could into the park.

"Milwaukee's been very careful about not developing the lakefront, which has huge positives, where, because it's all very accessible, it's all beautiful space. But when you're down here, it's nice to have some amenities so you can get a drink or use the restroom or whatever. I think we've added a lot to the function and the presence of this building."

The project to convert the building was not an easy one, Fowler says, noting that Colectivo – which was called Alterra back then and had just a couple locations – broke the budget twice over on the project.

"Back then we were a small coffee company," he says. "There was no food component to the business we did, and when we created this place it actually caused us to create our bakery (Troubadour), so this became a very large project both here at the lakefront and also down at the back end of what we do, and we were inventing stuff as we went along. I think we tripled our original budget, but we were committed to doing something of really high quality, so it was a challenge."

But it was a challenge, Fowler says, that transformed not only the flushing station building, but also the young Milwaukee coffee company.

"I remember thinking at the time it was kind of an existential event for us," Fowler says. "If we had not been able to be successful here or if the bakery lost any more money than it did – and it lost a lot of money – we may not have survived this organization, so it was super difficult.

"It was kind of a watershed event for the organization. It pushed us to create the whole bakery component, which was a massive challenge. But also the style, the internal aesthetic of our organization, evolved significantly with the development of this project. A lot of the design elements that we created for this project have actually carried through the rest of the organization, so it was definitely pivotal. This definitely kind of kicked us up to the next category of business."

Now, the lovely-but-silent building has been reborn. Actually, it is likely livelier than ever, having never had the kind of concentration of public activity that it boasts today. Jog past, or ride by on a bike or in your car and the lights are on, folks are going in and out. If the weather’s good, the patio is full.

On Thursday nights there’s live music, too.

"Again, you have to put yourself back when you drove past this building in the '80s and the '90s," Fowler says. "It was a pretty building, but that was it. Now it's become this wonderful interactive space, and really one of the first amenities along the lakefront for people who are down here."

Pass by today and there’s more activity, this time from construction crews who are working on the first phase of some exterior upgrades. Some of it is to make up for the limited capacity of the interior space and the pressure on it during the temperate season.

"It looks like a fairly grand, large structure, but when you get into the café, it's actually pretty small," says Fowler. "We actually built the whole second level to have to try to expand the seating, so it's always been a challenge. We have a lot of outdoor space here and a lot of ability to host people that way, but our ability to satisfy them has always been pretty constrained, because our production space is really microscopic."

The work will include changes to the seating areas outside and the installation of a coffee kiosk to ease some pressure on the counter inside during busy times. That work – along with the replacement of some of the outdoor surfaces is underway now.

MMSD, which still owns the building, has been working on the exterior, too, doing some tuckpointing and foundation work.

"As we go along, and this work is going to be done probably in two steps, we're doing a bit now, and then we're going to stop so we can have our customers have a nice space for the summertime," Fowler says. "Then in the fall, we'll be working a bit more.

"This building gets used pretty hard. There are a lot of people that pass through here, so we've done some internal improvements with our production space so we can produce more faster. The bathrooms are about to get redone. They've been obviously used pretty hard over the years and need some updating."

I asked Fowler if there are any secret spaces in the building, beyond the sunken pump equipment area, which I know has a door that accesses the impeller blades.

"It's pretty much what you see is what you get," he says. "There's no basement. There are no hidden spaces. You walk through, you see everything. We have been (in the cupola) to install an exhaust fan. But it's a fabulous building to occupy; it really is. It's unique."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.