If you watch this space, you know I've written a bit about vintage schoolhouses. Those pieces have usually focused a bit on history, a bit on architecture and on the building's public spaces. As a kid, at P.S. 199 in Brooklyn, the lower levels of the school were entirely off limits to students and thus seemed extremely mysterious to me.

So, when, thanks to the building engineer, I recently got an impromptu tour (so I apologize that some of the photos, taken with my iPhone, are low quality) of the building's spaces that are rarely seen by anyone beyond the engineer himself, it made me feel like a spelunking kid again.

It also gave me a new appreciation of why these potentially dangerous areas are no place for an unaccompanied child.

Built in 1887, with major additions in 1893 and 1951, Maryland Avenue School is typical of buildings from its era.

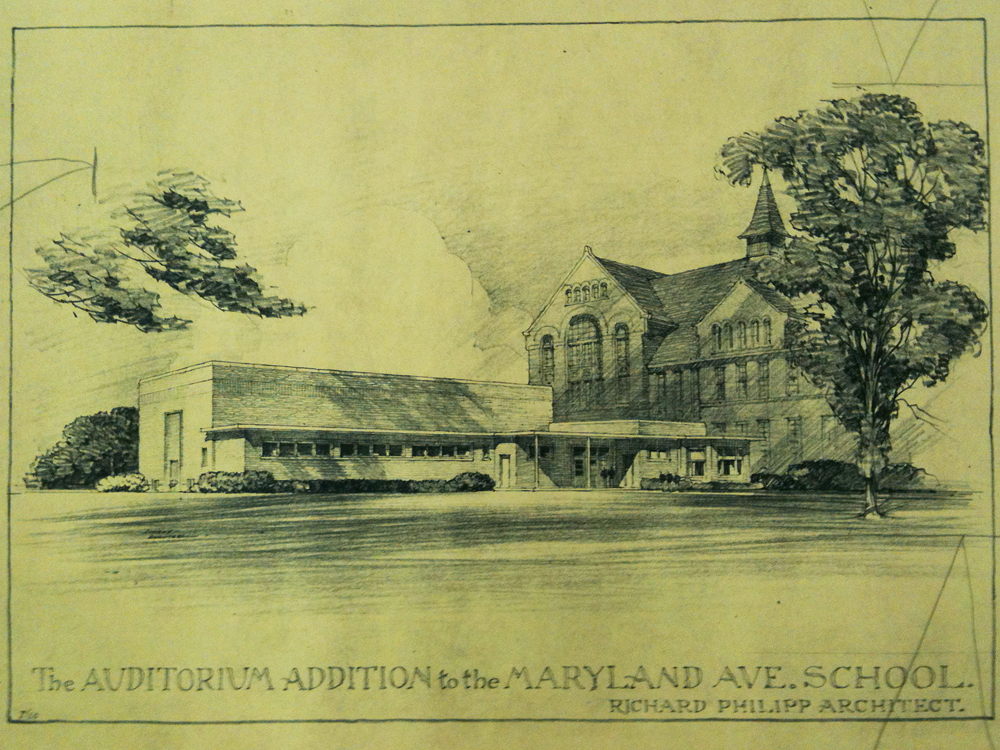

It's Romanesque Revival – at least Henry Koch's 1887 part is; Schnetzky and Liebert's 1893 addition is decked out in Queen Anne style and Richard Philipp's gymnateriatorium is boxy modern – with high ceilings and lots of windows, though many of those have long since been bricked up (either to create more wall space in the classrooms or to conserve energy, or both, depending upon whom you ask).

The original 1887 floor plan.

The original 1887 floor plan.

Going into the public area of the basement, you can easily spot where the 1887 building once ended and where it now snuggles up next to its 1893 counterpart.

A view you can no longer get. The south facade (ignore the erroneous "east" notation) before the 1893 addition.

Though we're below grade, we can go much deeper underground than you'd expect. Go down a few steps and you can enter the ventilation spaces. A door opens on a small closet-like space with two doors side by side.

On the left is a door so narrow you have to turn sideways to fit through it. But keep your hands close to your sides because along the left wall of a very cramped space is an approximately four-foot whirring fan blade that draws air down a hallway and a shaft that connect to a roof vent. Though the ornamental cap – often mistaken for a bell tower – is gone from the roof, the vent remains.

On the right is a wall composed entirely of filters – changed a few times a year – through which the air passes before reaching the fan, which then blows the air up into the public spaces of the building. On the other side of the filters is the passageway to the vent shaft.

Along the short passageway – maybe 10 or 12 feet long – you've got to plant your feet to avoid being blown over by the air flow. At the end, you can gaze three stories up the shaft to the attic, seeing the original building exterior (this shaft was added later) windows on the left.

Many of these old schoolhouses have giant attics. One such attic, at Vieau School in Walker's Point, was recently converted into classroom space. The one at Garfield School has two sides, separated by the ceiling of the third floor gym. To get from one side to the other, you climb a steep wooden ladder and walk across the beams of the gym ceiling.

The attic at this school is similarly large, but wide open thanks to the lack of a third floor gym, and is copiously adorned with old graffiti (Garfield, on the other hand, has only a couple scrawls). The oldest ones I've found date to the 1890s.

Back down in the basement, you can follow a switchback set of staircases into a subterranean boiler room that was built in the early '50s, when the gym and cafeteria were added to the building, too.

Richard Philipp's rendering if the gymnateriatorium.

Descending, I wonder what to expect. Will this boiler room be pretty cramped – almost entirely filled with the huge boiler – as at the apartment building I once managed?

No, what appears before me is a really big, open space, with two giant boilers – together they might fit on the back of a flatbed semi – and ceilings that must be at least 15 feet high. Off to the west is another large room, though smaller than the boiler room, that once had windows and a door along the top of one wall. But those have been bricked up, too.

That room is empty and the engineer is unsure of its original purpose. He says the by now unused openings were sealed up because they'd become leaky and it was easy for little four-legged critters to make their way in on a search for shelter.

Every day the engineer comes down to tend the boilers and there's an alarm system that notifies him 24 hours a day if the boiler should shut down unexpectedly. If that happens he's got to come to school and get it up and running again.

It's hard to believe that a couple levels up, hundreds of kids concentrate on their work without the slightest knowledge of the industrial scenes below.

Back up in the basement where there is a computer lab, bathrooms, the engineer's office (adjacent to a room that holds the school's electricity panel), an art room, a classroom and some offices, there is a small room that serves as a parent room (storage, basically, for the PTO's supplies and event materials). It is part of a boiler room added around 1920 that became redundant when the current boiler room was added.

Another door leads from the parent room into a room with a lovely hardwood floor that's perhaps 10x12 and is drywalled stark white. Here are the guts of the phone system, the WiFi, the computer network and the like. This is the technology hub and it stands in bright, temperature controlled contrast to the more workaday spaces below.

Before we go, there's one last space to check out. It is the area beneath the stage in the "new" 1950s addition. Past another heating unit, this one for water for the cafeteria and the bathrooms, is a space that's big enough to make a great classroom, which this school could really use.

The problem is that it has no windows, no heat, and is as damp as you'd expect such a basement space to be. And who wants kids nudging themselves past a giant grumbling water heater to spend the day in a damp, dark classroom with no emergency egress?

Back upstairs in the gym that's flooded with light, I realize I have a new appreciation not only for what it takes to keep a building like a school purring, but also for the folks that do it, day in and day out, providing a safe, comfortable atmosphere in which our kids can focus on learning.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.