Ninety years ago a Chicago boxer came to Milwaukee to fight for the junior welterweight championship of the world and got the beating of his life.

Not in the ring, though. It happened on a Downtown street the night before the big fight scheduled for Oct. 11, 1923 at the Auditorium.

William "Sailor" Friedman bragged he would return home with the diamond-studded championship belt. Instead, he almost went back in a hearse after three goons jumped him as he took a late night stroll on the eve of the fight. They forced him at gunpoint into their car, punched, kicked and pistol-whipped him, and left him bleeding in the gutter at 3rd and Clybourn Streets.

Most local boxing fans took the view that it couldn’t have happened to a more deserving fellow. Law enforcement agents here and in Chicago probably went along with that.

Before, during and after his boxing career, Sailor Friedman was mobbed up to the gills. A runaway at age 15, he went to work in a gambling house operated by Max "Boo Boo" Hoff, Philadelphia’s underworld chieftain who managed boxers and promoted fights on the side. Hoff and other mobsters handled the Sailor – Friedman started boxing when he was in the U.S. Navy – after he turned professional, and when the 1920s started roaring Friedman, then a resident of Chicago, was a big-name lightweight.

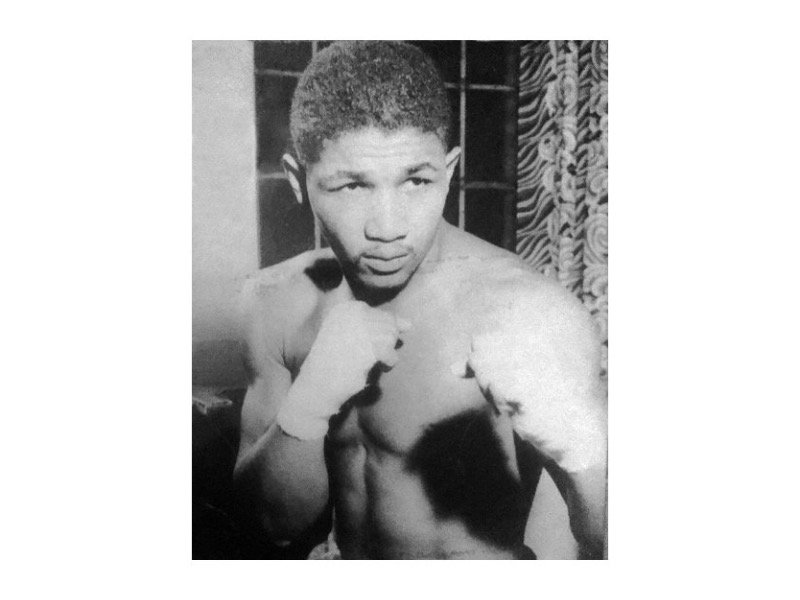

So were Richie and Pinkey Mitchell, the boxing brothers who grew up on W. National Ave. and became the brightest stars in local ring history.

In 1917, Richie Mitchell won a 10-round newspaper decision (official decisions weren’t allowed here until 1928) over Friedman at the Auditorium. On Aug. 9, 1919, they met again in Benton Harbor, Mich., and in the sixth round Mitchell knocked Friedman down twice.

At the bell, Friedman handler Dave Miller jumped into the ring and tackled Mitchell, and within moments Pinkey, who was in his brother’s corner, was slugging it out with Friedman partisans amidst a shower of bottles and chairs coming from the audience.

"A number of guns were flashed," recalled Richie several years later, "but fortunately none of our party carried a gat and the Chicago gang had no excuse for using them."

When order was restored, Pinkey Mitchell volunteered to tell Friedman, who’d ducked out to his dressing room when the melee broke out, that if he returned to the ring the fight could resume. Objecting to the message and the messenger, Friedman swung at Pinkey and they went at it bare-knuckled till the weary authorities recommended that all parties involved go back where they came from.

The Michigan boxing commission later suspended Friedman and Miller and barred them from state rings for one year.

The fireworks expected three months later when Pinkey and Friedman came out of opposite corners at the Lakeside Auditorium in Racine – "Little love exists between this pair and they’ll be out for blood a second after the opening gong clangs," wrote Chet Koeppel of the Milwaukee Sentinel – didn’t happen because Friedman did little more than show up for the fight.

"Do you think I’m foolish? Why should I take a chance with this fellow, a terrific hitter? I was out to stay 10 rounds and I succeeded," the Sailor told The Milwaukee Journal’s Sam Levy after the final bell.

In 1922, the careers of Pinkey Mitchell and Sailor Friedman were impacted by separate plebiscites. In Mitchell’s case, voters in a national contest sponsored by The Boxing Blade magazine in Minnesota elected him the ring’s first junior welterweight (140-pound) champion.

To this day, Pinkey is Milwaukee’s only recognized world titleholder, and the only one in the history of boxing to win his championship by popular vote.

Only 12 persons voted in the matter involving Sailor Friedman, and they convicted him of murder in a Chicago courtroom. On April 12, 1922, the Sailor’s sister told him that as she was walking along a Windy City street a car stopped and its male occupant tried to force her inside. He rounded up some pals and went to a west side saloon where shots were fired and an ex-con was killed.

Sentenced to 14 years in prison, Friedman ended up a free man a year later when a judge dismissed the charges against him.

Friedman vowed to belt Pinkey Mitchell clear out of the Auditorium in their championship bout on Oct. 11, and was so voluble about it that according to Manning Vaughan of the Sentinel he "almost caused a riot" in the lobby of his downtown hotel a couple nights before the fight.

He didn’t do much talking the next night when he woke up at Emergency Hospital.

The papers said he was too "hysterical" to be of much help to detectives investigating his assault. Later the Sailor was pretty sure he’d recognized one of his attackers as "a Milwaukee thug," but when local and Chicago gumshoes compared notes they wrote it off as a revenge beating carried out by members of the gang to which the guy Friedman was charged with killing the year before had belonged.

Nobody was ever arrested.

Friedman made a complete recovery, which was too bad for Ray Mitchell, who fought him a year later in Philly. After 10 hard rounds it was discovered that most of the padding had been removed from Friedman’s boxing gloves. The Pennsylvania boxing commission suspended the Sailor for a year for that one.

On Aug. 24, 1925, Friedman fought welterweight champion Mickey Walker in Chicago. In Walker’s dressing room beforehand, a visitor asked a favor of the 147-pound champion:

"The Sailor’s a friend of mine. Don’t hurt him."

It took extraordinary effort on the part of Walker, a truly great fighter, but he did as Al Capone asked. Friedman lasted the full 10 rounds.