In the excitement surrounding the end of the sadly mislabeled "War to End All Wars" 95 years ago this month, some people did things they wouldn’t otherwise have done.

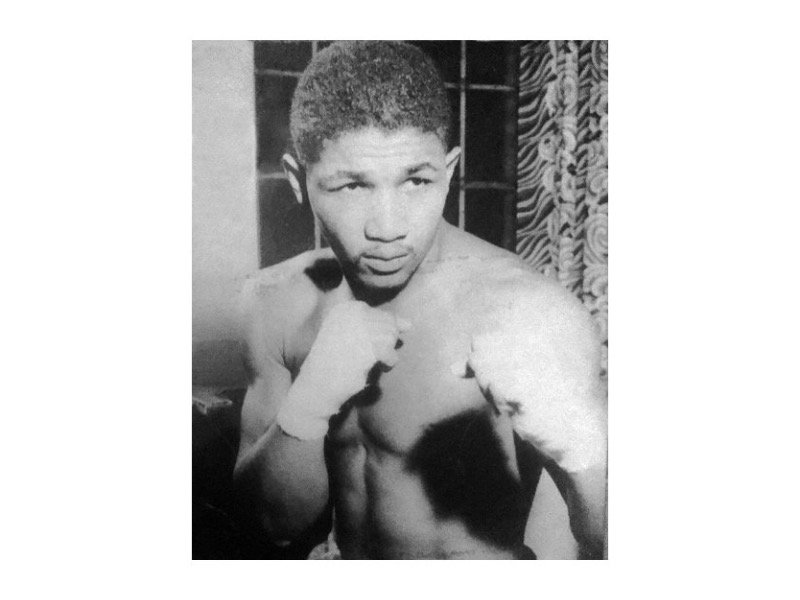

In the case of Walter H. Liginger, it was allowing one of the greatest boxers in history to fight in Milwaukee in spite of his black skin.

When boxing was legalized in Wisconsin in 1913, black fighters had been barred from fighting here because Liginger, czar of the commission established by the legislature to oversee the sport, believed that "Negro boxers have done more to put boxing in disrepute than all the white boxers in the game," and that "whenever there is a scandal, invariably there is a colored gentleman involved."

Those were his reasons for refusing to permit a fight in Milwaukee in 1914 between legendary black heavyweights Sam Langford and Sam McVey.

That was the second time Langford – "The Boston Tar Baby" – had been booted out of the Badger State. On May 30, 1911, he was scheduled to fight white journeyman Tony Caponi in Kenosha. That was before boxing was legal in Wisconsin, but fights were held nonetheless at the discretion of local officials.

Not this one, though. On the day of the fight Gov. Francis E. McGovern ordered Kenosha Sheriff Andrew Stahl to prevent it.

"Those who are close to the governor," reported the Milwaukee Sentinel, "say that he is not opposed to boxing matches, but will draw the line at any fight between a negro and a white man."

Authorities in Winnipeg, Manitoba, had no such qualms, and 17 days later Caponi and Langford (a native of Canada) squared off there. But when Sam was about to put his white opponent out in the seventh round, the police intervened and suggested that if he didn’t want to spend the night in jail he’d let Caponi finish the 10 round bout on his feet. Which is what happened.

"The man who was so good he was never given a chance to show how good he really was," said sportswriter Al Laney of Sam Langford.

It was a different story when the other guy was also black and there was no need for Langford to put on the brakes. When he fought Nate Dewey in Cheyenne, Wyoming, Langford announced to the crowd as the bout got underway: "Folks, you might as well get ready to go home, ‘cause Mr. Dewey ain’t going to be around very long. There’s a train for Los Angeles and Sam am going to be on it."

One punch later, he was on his way.

Langford once joked that he would have been heavyweight champion of the world if Mother Nature had dipped him in a bucket of whitewash instead of tar. Only it was no joke.

He never got the opportunity in his prime because bowling over White Hopes was easier and more lucrative for Jack Johnson. The smiling ease with which the first black heavyweight champion did it, plus his unapologetically sybaritic lifestyle, totally unhinged white society.

"It is a burning shame that some heavyweight white man cannot be soon developed to take away the championship from this unworthy colored man," bemoaned the Milwaukee Sentinel’s "Sporting Arbiter" on July 5, 1914. "The fact that Johnson is champion is not merely a disgrace to the manifest possibilities of the white race, but it has a bad influence on the colored race. In the names of humanity and decency, let us soon find a white man who can lick the immortal tar out of this great big arrogant black champion."

That finally happened a year later, but Walter Liginger staunchly continued to draw the color line in Wisconsin until early November 1918. World War I was winding down, and Liginger was named to spearhead Milwaukee’s effort to help the United War Fund raise $170 million. A "monster boxing show" at the Auditorium on Nov. 29 was the centerpiece of the local campaign, with the famous Sam Langford fighting the 10-round main event against Jeff Clark, another talented black boxer.

It wasn’t that Liginger had suddenly gone squishy soft in his regard for black fighters. "A bout between negroes would be a novelty here and it is believed would draw a capacity house," noted The Milwaukee Journal on November 5.

In addition, Langford and Clark had just fought two torrid matches against each other that ended as draws, which was remarkable given that then Sam was at least in his late 40s and half blind.

When they agreed to fight again in Milwaukee, the city had just spent three weeks and three days in quarantine on account of the historic flu epidemic, with schools, theaters, churches and other public gathering places shut down. Health Commissioner George C. Ruhland lifted the ban on Nov. 4, but warned that it could be reimposed at any time.

Uncertain, therefore, whether their Milwaukee fight was a sure thing, Langford and Clark agreed to a six-round match in Philadelphia on Nov. 28 before they got word that their bout here was locked in.

In Philly, Clark knocked Langford down in the first round and got the decision. Then they grabbed the first rattler for Milwaukee and made it here just hours before climbing into the Auditorium ring.

They probably wished they hadn’t bothered.

"Colored men of the ring were put on trial at the Auditorium Friday night and if the bout between Sam Langford and Jeff Clark can be taken as a criterion, Milwaukee doesn’t want any more of the dusky gentlemen for a long time," wrote Manning Vaughan in the Sentinel the next day. "It was a slow, uninteresting exhibition, with Langford having what shade there was."

"Only three or four times during the bout did the black boys show any real inclination to mix things, though they cut some vicious grimaces and tore the atmosphere several times with some frightfully wild swings."

The Milwaukee Leader called the bout "interesting and speedy," but Sam Levy of the Journal reported that while "both men did considerable damage to each other," some observers thought the fight "merely a dress rehearsal" – a put-up job.

Including Walter Liginger.

"It was the first and last match between negroes in Wisconsin," declared the boxing solon. "They have tried and tried to break in here and finally were accommodated, but the showing last night has convinced the people they want no more of them."

Langford and Clark were ordered to account for themselves at a commission hearing the next day.

"I surely think I did all I could to go through with my end," said Langford. "I boxed in Philadelphia Thursday afternoon, rode on the (train) for 24 hours and then boxed again Friday night. They call me ‘Old Man Langford’; some say I am 40, some 50, some 60, and just because I did not put out Mr. Clark here they say funny things about that."

Then came a rhetorical haymaker that landed right on Liginger’s glass jaw:

"I sure did the best I could, and if that bout had been between two white men it would have been praised to the skies."

Langford and Clark escaped suspension only by donating $100 each to the United War Fund, which meant they fought for nothing.

"All right, guv’nor," the unflappably dignified Langford said to Liginger, "but I hope you give the colored boys a chance to box in this state."

It didn’t happen again, though, for 12 more years.