This weekend, This is It, 418 E. Wells St., celebrates a golden anniversary of national historic importance. Staff, guests and visiting dignitaries – including Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett – will mix and mingle at the jubilee of the summer.

Since 1968, this Cathedral Square classic has been a consistent LGBTQ landmark, making it one of the top 10 longest-running gay bars in the nation, and quite possibly one of the top five. For so many, many reasons, this is a triumph not only for the bar itself but for the greater community.

As This Is It honors its past 50 years with an action-packed weekend schedule, its owners have announced – stop the presses! – ambitious plans to expand at its current address. Details are forthcoming, but the vision and commitment are clear.

"We will maintain the integrity and aesthetic of the original bar, while creating an exciting new performance and dance space for our customers," said George Schneider, co-owner of This is It. "We are fully committed to an expansion so precise and perfect that you’d never know the bar had even been expanded."

"Wood paneling and wall carpet purveyors beware," Schneider added cryptically. "This Is It will soon be seeking your services."

The bar’s last significant remodel took place in 1969, but This Is It has seen subtle changes in recent years, including the installation of new carpeting and tables, an extended bar counter, digital registers, a TouchTunes jukebox and gender neutral restrooms. Less subtle, the long-discrete bar is now decorated with a rainbow-themed façade, as well as a prominent pride flag.

Events, including movie nights, ice cream socials, karaoke, bingo, fundraisers, book signings, show tunes singalongs, sports games, awards ceremonies, doggy happy hours and trivia, have become as diverse as the bar’s customer base. The bar has hosted national drag entertainers, including Sherry Vine, Aquaria and Katya, as well as returning Milwaukee icons like Trixie Mattel, Jaymes Mansfield and Linux the Robot.

"We walk a careful balancing act between maintaining the loyalty of longtime customers, engaging the emerging generation and staying on the cutting edge," said Schneider. "On any given Saturday night, you’ll see the first-timers in here, and the Cathedral Square bar-hoppers, and the bachelorette parties, but you’ll also see Tracy from the Mint Bar looking fabulous, and Barney, who is well into his 90s, and people from every generation of the bar mixing, mingling and making conversation. That’s the welcoming family environment that we foster.

"It’s not 1987 where you can hang a rainbow flag outside and count on customers to support you. Gay bars are not the only safe haven anymore. Everything is changing. We need to be creative in preserving this space, and this experience, while securing our next 50 years of business."

The brave and the bold

The bar business is a fleeting one. Even in Milwaukee, second only to New Orleans for the number of bars per household, it’s difficult to name another bar that has been continuously operating at the same location under the same name for 50 years.

When you consider the scorn that LGBTQ people faced in the 1960s, it’s almost unthinkable that This Is It ever opened – much less survived to this day. Being gay was not just a crime, but seen by society as a symptom of a serious mental illness. Serving alcohol to "known" homosexuals was actually illegal, and bars could and would lose their licenses for allowing homosexuals to congregate on the premises. Men could be arrested for dancing together. Technically, two men who did not know each other could not turn to face each other at a bar, nor sit together on neighboring bar stools. Anyone suspected of being homosexual – based solely on the bartender or manager’s opinion – could be asked to leave or forcibly removed.

"It could be something as simple as not flirting with the only woman in the bar," said Bunny, an LGBTQ community elder and contributor to the Wisconsin LGBT History Project. "It could be not laughing at a dirty joke. It could be not having a deep enough voice. It could be anything. Anything at all. And you were out."

Banished from straight taverns, midcentury Milwaukee’s gay and lesbian community found solace in a rich underworld of hotel parties, secret backrooms and cruising grounds. By the 1950s, known gay bars began to concentrate on the south end of Downtown, including the Fox Bar (455 N. Plankinton Ave.), Tony’s Riviera (formerly the Anchor Inn at 400 N. Plankinton Ave.), Mary’s Tavern (formerly the Old Mill Inn at 401 N. Plankinton Ave.), the Crystal Palace (400 N. Water St., in the Cross Keys Hotel) and the short-lived Pink Glove (631 N. Broadway), believed to the be the first bar designed and marketed to gay people in Milwaukee.

The Seaway Inn opened at Jefferson and Mason in 1959, replacing the long-running Ambrosia House restaurant, and the new gladiator-themed Columns cocktail bar at The Pfister Hotel was an immediate gay hotspot by 1961. Across the river, another collection of Downtown gay bars took form, with the Mint Bar (422 W. State St.), the Clifton Hotel Bar (336 W. Juneau Ave.), the Royal Hotel Bar (435 W. Michigan St.), Baron’s Gay 90s (5th and Michigan) and the legendary Castaways (424 W. McKinley Ave.), known as the first place in Wisconsin that not only allowed same-sex dancing, but encouraged it as early as 1961.

The Clifton Tap (PHOTO: Historic Photo Collection/Milwaukee Public Library)

The Clifton Tap (PHOTO: Historic Photo Collection/Milwaukee Public Library)

Various others were scattered around the city, including the Pink Pony (1834 W. North Ave.), Wagon Wheel (4100 W. Lisbon Ave.), the White Horse (1426 N. 11th St.), the Bull Ring (1250 N. 12th St.), the Forum (1801 N. 12th St.), the Bridgeport (3762 N. Green Bay Ave.), the Nite Beat (901 W. National Ave.) and Your Place (813 S. 1st St.), the first major men’s bar in Walker’s Point.

Although there were many, many nightspots to choose from – if you knew the right people, in these strictly confidential, word-of-mouth times before the gay press – these early bars weren’t always the best experiences. Because they were often operating under the radar, unadvertised and/or unlicensed, they didn’t feel they had to. After all, they held a captive audience that had nowhere else to go.

"When my gay friends would take me out, we would go to some of the rattiest places imaginable," said June Brehm in April 2008. "The liquor bottles weren’t even marked, and they were always watered down. The lights were so low you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. The music – if there was music – was playing on a cheap old record player that barely worked. People were afraid to dance. There was never any ice. Never! The beer was always warm. The only food they served was stale chips. You were lucky if the toilets worked. And on top of that, you had to worry about being arrested just for being there! It made me sad. I said I would never put up with this, so why should they?

"I knew these boys deserved better and I thought, to hell with it, I’m going to find them someplace better if I have to open it myself."

And that’s exactly what she did. Already a wife, mother and successful business owner, Brehm persisted with her dream of an inclusive Downtown bar and grill. After a long day of touring tavern spaces, she took a look at the one at 418 E. Wells St., formerly known as The Establishment. She turned around and said to her original business partner, "This is it. We aren’t going anywhere else."

This Is It was born.

June Brehm

June Brehm

Five decades of forward thinking

When This Is It opened in 1968, there wasn’t much happening in Cathedral Square. Urban renewal had really decimated the surrounding area, and it would be decades before it would truly feel restored to life. Most of the aforementioned gay bars were long gone, flattened for freeway construction, targeted by slum clearance or abandoned by white flight, as the new gay neighborhood formed around 2nd and Pittsburgh in Walker's Point.

Offering anytime food service and classic cocktails, the space became an extremely popular man’s bar. Brehm and her family became the chosen family of their patrons, many of whom had been rejected by their own. The bar was always open on holidays, offering Easter, Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s meals, even if the doors to family celebrations were firmly slammed shut.

When being seen at a gay bar was still a career-limiting, socially-damaging move, This Is It offered privacy and discretion even in broad daylight. Early customers were more likely to use the back entrance, which led to not only the back alley but a now-closed passage that led to Jefferson Street. Closeted men could take advantage of the bar’s low lighting to avoid anyone they didn’t want to see.

"It still takes your eyes awhile to adjust when you walk into This Is It," said June's son Joe Brehm in 2008. "Just long enough to make a back door exit!"

However, June’s original business partner wasn’t always supportive of these accommodations. He was known to sit, scowl and watch customers from the far end of the bar, always on the lookout for anyone who crossed the line into behavior that was "too gay."

"He had cold feet about letting so many gay men hang out here … worried about people thinking this was a ‘gay place,’" Joe Brehm said in May 2008. "And she would get so angry, just so angry. She would get red in the face arguing with him, and he would just keep nagging her. He told her we’d lose the license, we’d never have respectable customers, we would lose our suppliers, just all this trash talk that was outdated even back then.

"And these men were like her family, you know – not just paying customers but really important friends, people that she cared about. So he wasn’t just insulting them; he was insulting her.

"Finally, one day, with a bar full of people, she pulled out two $5 bills and asked him which one was gay and which one was straight. He didn’t understand the question at first, but then he got real quiet. And she said, ‘Until you can tell me the difference, I’m going to serve whoever walks in that door ... I’ll serve whoever the hell I want!’ The whole bar cheered. After that, he didn’t come around the bar much."

Needless to say, June and her vision prevailed long after her original partner exited the business. She and her husband took full ownership of This Is It in 1971. Soon after, welcoming print ads began to run in the Gay People’s Union (GPU) News. While the restaurant function ultimately closed – reportedly because it attracted "too many straight people" who made the regulars feel uncomfortable – the kitchen remained open for special events.

Even after Joe assumed management of the bar in the 1980s, June continued to visit This Is It every morning to do bookkeeping, ordering, banking and other financial transactions. This routine continued until she was well into her 90s. She maintained strong, lifelong relationships with the first vendors and bankers who extended credit to the business. She was on a first name basis with everyone.

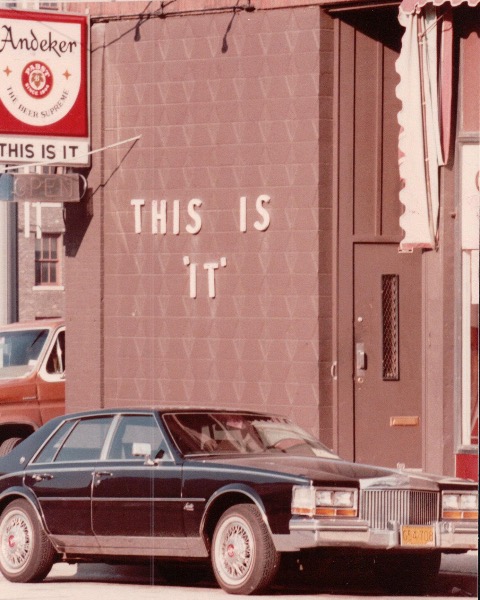

"Andeker and Pabst were among the first breweries that would allow their signs to hang outside a gay bar," said Schneider. "June never forgot that kindness."

June and her son Joe Brehm, long-time owners of the bar.

June and her son Joe Brehm, long-time owners of the bar.

Back when the bar accepted checks, June was the one who called to collect from customers when their checks bounced. She began these early morning calls with a strong-arm, scolding stance that eventually warmed into a warm, compassionate and accommodating approach.

"She was tough, don’t get me wrong, especially if she felt someone had cheated her. But if someone was going through a really hard time, she would go through that hard time with them," Joe Brehm said in 2008.

"When AIDS started, we lost so many customers. Just so many. You have no idea what that was like. So many faces that we just never saw again and didn’t ever know what happened to them. They wouldn’t even run obituaries sometimes because the family was ashamed. But when they got sick and stopped coming to the bar, and we’d find out why, she would call them up and let them know she missed them and make sure they would care of themselves. Oh, those were hard calls. People were so scared, and many times, so alone. So many people died alone. Their own families wouldn’t call them and check on them. But she did."

Mother of two, grandmother of five, great-grandmother of six, and spiritual mother to hundreds if not thousands of long-time customers, June Brehm passed away on Jan. 3, 2010 at the age of 92.

Generation next

When he was "freshly 21," George Schneider visited This Is It for the first time.

"My friend Aaron told me, 'Hey, this place is really different from the other gay bars, but it’s chill and you’re going to like it,'" said Schneider. "And it was the weirdest thing, because I stopped myself as I was walking in, right by the old cigarette machine. I was overcome with this déjà vu feeling, but also a feeling of meaningful belong. I said, I’m supposed to be here, I’m meant to be here. And someday, I’m going to work here. At the time, that made no sense because I had never worked in a bar or a restaurant."

While living and working Downtown years later, This Is It became Schneider’s favorite after work spot. He developed a relationship with Joe Brehm, from whom he bought the bar’s old jukebox. Later yet, he started working at the bar part-time while pursuing his next full-time role. Over the next 18 months, he took on more and more shared management functions.

Upon receiving a new job opportunity, Schneider also received an important message from Joe: "Before you say yes, I’d like to talk to you."

"I never thought Joe wanted to invite me into a partnership," Schneider said. "I knew what I was doing was important to the bar, but our relationship had always been more professional than personal. I never thought he would make this offer. I was so honored."

Joe Brehm and George Schneider in 2015.

Joe Brehm and George Schneider in 2015.

In August 2015, Joe was diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease). He passed away on April 3, 2016. As a generous supporter of local causes, organizations, events and individuals, as well as a cherished friend and father figure to so many loyal customers, Joe was deeply missed by Milwaukee’s LGBTQ community.

For the first time in four decades, the bar would be operated outside the Brehm family. Some worried that this community treasure might quietly close, but Schneider insists that was never an option.

"I knew I had to do something to protect the business," said Schneider, "because I knew I couldn’t do this on my own. So, much as Joe saw passion, skill and ownership in me, I sought out the same in a business partner. Fortunately, I found that person in Michael Fisher, who stepped up from bartender to partner in late 2016."

Since then, Fisher and Schneider have been co-owners of This Is it.

With the anniversary approaching, Schneider has become both a teacher and a student of the bar’s history. He’s heard many interesting stories about the olden days and learned quite a bit more about Joe, June and the business.

"I got to see a more personal side of them that I never knew," said Schneider. "When I met Joe, he was already in his golden years. I didn’t know him when he was my age and running this bar, but I now think we have the same spirit, just separated by time. This has been an unexpected reward of all this party planning."

Schneider has received a number of interesting artifacts, including a full jar of bar tokens, sports team memorabilia, neon beer signs and historic pride posters, some of which have been donated to the UWM LGBTQ Archives. He’s also located the long-lost eight storefront letters.

"When Joe came into the business, he decided to take down the signage because MSOE students were constantly rearranging the letters into inappropriate messages. If you look at the letters in THIS IS IT, you can probably guess what those were," Schneider said. "When I found them in the basement, even Joe didn’t know they were still around."

Over the years, the bar accumulated thousands of photos that compose today’s digital show reels. George estimates that over 2,500 historic photos are already running on the bar’s TVs, with another 5,000 waiting to be scanned into the collection. Recently, former bartender John "King" Kraus donated another 100 to the collection. New photos are constantly added – either by bar staff or patrons sharing their own – creating a never-ending stream for all to experience and enjoy.

"Everyone loves being part of our long and colorful story," said George. "Every night, we are making history."

In 2016, This Is It made an appeal for Milwaukee to implement rainbow crosswalks in Cathedral Square. While the request is still pending with the Department of Public Works, 16 other American cities have already installed them.

America’s disappearing LGBTQ landmarks

Admittedly, This Is It was more of a not-spot than a hot spot for young gay men of my generation. By the 1990s, the bar was known mostly by its mean-spirited nicknames, "This Is Old," "The Wrinkle Room" and "God’s Waiting Room." My cast of characters would only visit twice a year: during Jazz in the Park and during Bastille Days. We thought we had other, bigger, better options back then, when Milwaukee still had two to three dozen operating gay bars.

In spring 2008, I was asked by the now-defunct QLifeNews to write a story commemorating the 40th anniversary of This Is It. I spent countless hours at the bar, interviewing Joe and June Brehm, their bartenders, their long-time patrons, and even first-time visitors. Maybe it was the "Mad Men" cocktail culture nostalgia of that era, but I saw something truly remarkable happening during these visits. This Is It wasn’t just an older gentlemen’s bar anymore. It wasn’t just a happy hour hideout anymore. It had become a real destination again, for people from all walks of life, seven days a week, all hours of operation.

Since I wrote that article, the gay bar landscape has changed significantly. Milwaukee has seen a dramatic reduction in LGBTQ nightlife, with 16 of 23 gay bars closing since 2008. In fact, sociologist Greggor Mattson estimates that more than one-third of all American gay bars have closed since 2008. Shockingly, these have included some of the oldest gay bars in the country, including San Francisco’s Gangway (2017), Seattle’s Double Header (2016), New York’s Candle Bar (2015), and Chicago’s Lost and Found (2008).

Determining the oldest gay bars in America is a challenging task. Accepting 1933 as the end of Prohibition and the start of modern bar history, researchers believe Provincetown’s Atlantic House, New Orleans’ Café Lafitte in Exile, Oakland’s White Horse Tavern and New York City’s Julius’ are now the oldest in the country. But even these icons were not openly "gay friendly" until the 1950s – and even then, reluctantly and/or quietly so. In the case of Café Lafitte, the bar is operating at its second address after being exiled from its original location in 1953.

What about the legendary Stonewall Inn, so near and dear to the concept of gay liberation? It was America’s first national monument based on LGBTQ history and culture, as well as the one of the first LGBTQ sites added to the National Register of Historic Places. Yet, few people realize that the bar closed shortly after the June 1969 riots. When it reopened in 1990 at the same address, using half the original space, it used the abbreviated "Stonewall" name until closing again in 2006. Reopening in 2007, finally back under the original name of Stonewall Inn, the bar has enjoyed eleven years of tremendous success.

Meanwhile, This Is it was open throughout it all, continuously operating as a self-identified LGBTQ bar, at the same address, with the same name, within the same architecture for 50 full years. Its closest Wisconsin competitor, the dearly departed Mint Bar (1949-1986), could only hold that claim for 37.

So, how does it feel to own one of the oldest gay bars in the country?

"The weight of this important legacy is always there, but it’s a motivator and it makes me determined to carry it forward," said Schneider. "It makes me look to the future, while making good everyday on the promises I made to everyone who’s ever come through that door. Michael and I carry an obligation to be the custodians of this history and carry this legacy forward. It really can’t be said enough.

"I know that Joe and June would be real proud of what’s happening here. I know that Joe’s daughters and widow will be proud of what’s happening here. And that’s what matters most."

Want to learn more? Explore nearly 100 years of local LGBTQ heritage at the Wisconsin LGBT History Project website and the new book, LGBT Milwaukee.