"Bar Month" at OnMilwaukee is brought to you by Miller Brewing Company, calling Milwaukee home since 1855. For the entire month of March, we're serving up fun articles on bars, clubs and beverages – including guides, the latest trends, bar reviews, the results of our Best of Bars poll and more. Grab a designated driver and dive in!

When James McCartney returns to Milwaukee to perform at Shank Hall on Friday, April 14, he’ll be part of a circle that few people realize even exists.

That’s because the 28-year-old rock club on Milwaukee’s lower East Side has a "secret" musical history that almost nobody remembers. Even Shank Hall owner Peter Jest was surprised when I told him about it while working on this post.

James McCartney on stage at Shank Hall. (PHOTO: Peter Jest)

For years, the building long housed a garage, and in the most recent decades it’s been home to a music club. But what about the time in between?

The building is actually two buildings.

The front is a single-story, flat-roofed brick structure with a concrete floor and no basement. But at the back, there’s a two-story gabled building that looks more like an old home or coach house, but the details are fuzzy at best.

While the Wisconsin Historical Society lists 1920 as a date of construction for the two buildings, the one in the back looks quite a bit older. Walk down the narrow alley running along the south side of the building and you can quite obviously see where one was added to the other.

To further complicate things, a look back at the Sanborn insurance maps shows that both structures already occupied the land in 1910. The lot is shown as vacant on the 1894 map.

Then there’s a handwritten note on a 1931 permit held at the City’s Department of City Development that reads "this buildings has been occupied as a public garage for at least 52 years."

Huh?

Fifty-two is a pretty specific number, and one that suggests that it was built in 1879 or before. The back structure certainly looks like it could be that old, with its pair of gabled window bays on the second floor, facing east. There are windows on all other sides, too, though it’s impossible to tell what the front looked like since the lower building is now there.

The front part, with its heavy steel beam roof construction, is unlikely anywhere near as old.

The Sanborn maps do show homes and rear coach houses on neighboring properties. Is it possible that one of these was moved and now forms the back part of Shank Hall? Maybe.

The basement of the back building has rings embedded in the masonry of the east wall of the basement, suggesting a history as a coach house and a place to keep horses.

There are also closed-up doorways – including a wider one than you’d expect in a private home – facing Farwell Avenue. Perhaps the front section of the lot was sloped to allow horses to enter through these doors.

What we can say is that by the 1930s, the front building had been added and the building was in use as a garage – run by an R. Mages – for the storage and repair of automobiles. In 1938, we know it was called Farwell Avenue Garage, run by fellow named Cleary. By 1940, Lawrence Miller – who lived nearby on Warren Avenue – operated the auto repair shop there, giving way later that year to Clarence Williams.

At this point, the only toilets were in the basement of the back building. But that would change in 1947, when offices were created at the front of the building – in the area where the Shank Hall bar is now located – for a new tenant. At the same time, a skylight in the middle of the one-story building was removed and men’s and women’s rooms were added in the back right corner, up on the mezzanine behind the stage (pictured below).

That tenant was the most exciting find of my research. Beginning in June 1947, the building became the Wisconsin home of Capitol Records Distribution, whose job was the distribution of "phono(graph) records."

Capitol was founded in 1942, and by ‘46 had already sold nearly 50 million records and had become one of the "Big Six" American major record labels.

That means the groundbreaking, popular records that hometown boy Les Paul made with Mary Ford for the label were distributed out of what is now Shank Hall. All the fine records made at that point by Nat King Cole (who had been recorded at Milwaukee’s LaSalle Hotel in ‘46) would have come through the building on their way to local shops.

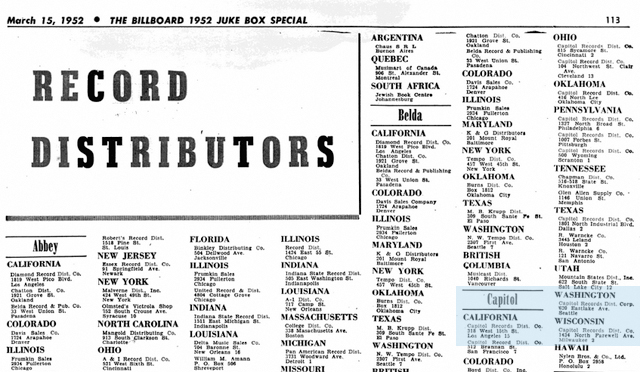

A 1952 issue of Billboard has a list of all the record label distribution hubs around the country and Capitol’s at 1434 N. Farwell Ave. is included there. Three years later, Britain’s EMI bought Capitol and the distribution center remained in place on Milwaukee’s lower East Side.

In the ‘50s, the building would’ve been full of 78s, then 45s and LPs by Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Louis Prima, Tennessee Ernie Ford and, yes, Bozo the Clown.

But the most exciting era for us rock and roll fans was about to arrive. In late 1962, cartons of "Surfin’ Safari," the first Capitol album by the Beach Boys, would have been carried into the building for distribution to area record shops, like Downtown’s legendary Radio Doctors shop on 3rd and Wells.

When Capitol boss Alan Livingston rush-released the 45 of The Beatles’ "I Want to Hold Your Hand" on Capitol’s swirling orange and yellow label on the day after Christmas in 1963, boxes of them surely landed on Farwell Avenue.

Less than a month later, "Meet the Beatles" would arrive, too. And by February, when the Fab Four performed on "The Ed Sullivan Show," Beatlemania was in full effect and the Farwell Avenue distribution center must have been a hive of activity.

It would be fun to think that John, Paul, George and Ringo popped in to say hello when they played in Milwaukee in September 1964, but none of the accounts of that whirlwind day suggest such a visit occurred.

By late 1965, The Beatles were in transition, as evidenced by "Rubber Soul," released in early December in the U.S., and so was 1434 N. Farwell Ave. Capitol had closed its distribution center there and the office space was converted into a retail shop, which likely maintained a link to the Beatles.

The Record Farm music shop opened in October 1965, but would prove short-lived. By late ‘67, the space was again being remodeled, this time for a tavern. During the record shop years, the space behind was returned to use as a garage.

In 1968, Tony Machi opened The Barn, whose distinctive wood facade – resembling a barn (natch) – would survive into the Shank Hall era. In 1970, there was a fire, but the place was fixed and re-opened.

By 1973, it was renamed Teddy’s, for Machi’s son Ted, and a stage along the south wall of the bar – about halfway back in the main room – hosted local and national live music.

A backstage room for performers at Shank Hall.

John Lee Hooker played there in the early days, as did Muddy Waters, who played five straight nights to close out 1974 (after having done similar stints there in ‘73, too). Dave Van Ronk and Babe Ruth also played there.

In ‘1975, Machi renovated the place, embracing disco, but that appears to have been short-lived. The most memorable feature of this era of Teddy’s was the mechanical bull (the saddle survives today in the attic).

The music continued during this era, however, and in 1976, jazz great Charles Mingus performed on the small stage with his band.

Charles Mingus and his band at Teddy's in 1976.

(PHOTO: Kevin Lynch/Courtesy of the photographer and Milwaukee Jazz Vision)

Soon, influential local bands like The Haskels were playing at Teddy’s and by 1984 touring punk bands like Black Flag, Subhumans and TSOL were on the bill there, too.

But when the drinking age in Wisconsin was raised from 18 to 19 in 1984 – and it became clear that it would soon rise to 21 – live music clubs took a hit, and Teddy’s soon gave way to The Funny Bone, which lasted, according to Shank owner Jest, until New Year’s Eve 1988.

"The whole year it was empty until I opened November of '89," Jest says. "Jim Wiechmann owned the Fenwick office building next door, and then he bought this to sort of protect his business (and) make sure it wasn't something goofy.

"When The Funny Bone went out of business, he was looking for a renter. I'm 24, 25 at the time, and Century Hall had just burned down. Odd Rock was not long for this world, and by then, The Toad was more of a bar. I sort of knew we needed a place for live music. And this was a historic location. So this was it."

Jest bought the building in 1999 (he'd been renting before), and Shank Hall (named after a fabled club in the film "This is Spinal Tap") has now been open for nearly 30 years, which might make some of us feel pretty old ourselves.

After a fire around the same time, Jest heavily remodeled the club, putting on a new facade, removing a plexiglass wall (that had melted into a blob in the blaze) that separated the bar from the music area, updating the bar area, and adding a bathroom and an egress that allowed him to boost his capacity from 240 to 300.

"(We) sort of opened it up," he says. "There's not a bad seat in the house now, which is good for what we do. We're a music venue."

Jest takes me to the basement, which I’d never seen, to show me the bricked up doorways and the extremely high ceiling for a basement and, especially, the rings in the masonry that seem likely to have been for tying up horses.

Then we go upstairs to the attic, which I had seen a few times before when the space served as backstage for bands at Teddy’s and in the early days of Shank Hall. But my appreciation for construction and the skilled trades wasn’t quite as developed when I was 18 and in my early 20s, and so when we climbed the steps, I saw it with new eyes.

There’s no ceiling up here, so you can see the intersecting grids of joists that almost create an Escher-like scene. You can also see the inside of those great three-window bays whose tops are dormered into the roof.

There’s also some stuff stored up here, though not much. But the stained glass panels and the crumbling leather saddle from the mechanical bull at Teddy’s are here (both are pictured below), along with posters advertising old concerts and beer.

One of the windows opens, affording access to the roof of the low, front building and from here you can get a close-up view of the beautiful carpentry work of the eaves.

Could this attic have been a hayloft?

Sadly, this will all disappear soon, says Jest.

"Unfortunately, we're going to tear all this down and bring it level to the (lower) roof, because the (east) wall is leaning," he says, gesturing to a big crack in the masonry. A series of metal wires is helping to keep the wall from falling to the parking lots behind it.

"This summer we're going to tear it all down and put a new roof on, and then put a new roof on the main part, too. It doesn't make sense to build that wall back up for a place we don't use. There's no heat, no air-conditioning, squirrels get in. I know this has historic value, but we’ve got to sort of get rid of it."

The space is beautiful and you can imagine the possibilities, but they all come with a price tag. There’s no insulation, no second exit in case of emergency and, as Jest notes, there’s no heat or air conditioning. And there’s plenty of proof that birds and squirrels visit far more often than humans do.

And then there’s the cost of rebuilding the back wall. I’ll be sad to see it go, but I can’t blame him for his decision.

As for the club itself, at 28 years running, Jest surely most hold some sort of record for the longest-operating rock and roll club in Milwaukee. He’s hoping to make it to 40.

"That’s only 12 years," he says. "I think I can do it."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.