’Tis Dining Month, the tastiest time of year! This means we’re dishing up fun and fascinating food content throughout October. Dig in, Milwaukee!

In honor of Dining Month, we're resharing this story of a classic Milwaukee restaurant (and, now, bar!). Enjoy!

While there are a number of landmark Milwaukee restaurants, there is perhaps no restaurant that says "Brew City" more than Mader’s, 1041 N. Old World 3rd St.

While we’ve lost a few similar places – I’m thinking Karl Ratszch’s and John Ernest Cafe, for a start – Mader’s has survived, plating the Old World German specialties for which its always been known, but in a brighter, more modern way.

The result is that Mader’s has not only survived, it appears to be thriving.

When I stopped over for lunch recently, I arrived early to take a few photos. By the time the door was unlocked at 11:30 a.m., more than a dozen folks were lined up waiting to get inside.

That’s where they found exactly what they were waiting for: a German-American restaurant blending elements of fine and casual dining, along with the de rigueur lineup of ceramic beer steins, old photos from the restaurant’s history, vintage chandeliers, a seriously antique suit of armor and, of course, that food.

While it might seem like Mader’s never changes, it does, albeit subtly.

The sublime potato pancakes are still there, but they arrive on an oval white plate with swoosh of apple sauce. The schnitzel is crispy as ever, but comes with more reasonably sized sides of sauerkraut and spaetzle instead of the pound and a half that used to arrive.

That slow, simmering accommodation to the passage of time and the changing of tastes is why the restaurant Charles Mader started – at least in its original form – in 1902 still has a dozen diners waiting for the doors to open on a weekday morning.

A bit of history

Charles Mader was born on May 25, 1875 in Germersheim, a town in the Rhineland-Palatinate (fewer than 40 miles from the town where my own Milwaukee German roots lie), which was part of Bavaria from 1814. The surname is a deep-rooted one in Germersheim and a search on a genealogy website turns up more than 10,250 results for the name in the town.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Sailing from Liverpool on the Cunard Line's Campania, Mader arrived at Ellis Island on Nov. 24, 1901, where after being eyed up and down by an immigrant inspector, was deemed to stand 5-foot-3-and-a-half inches tall, weight 180 pounds and have dark eyes and hair.

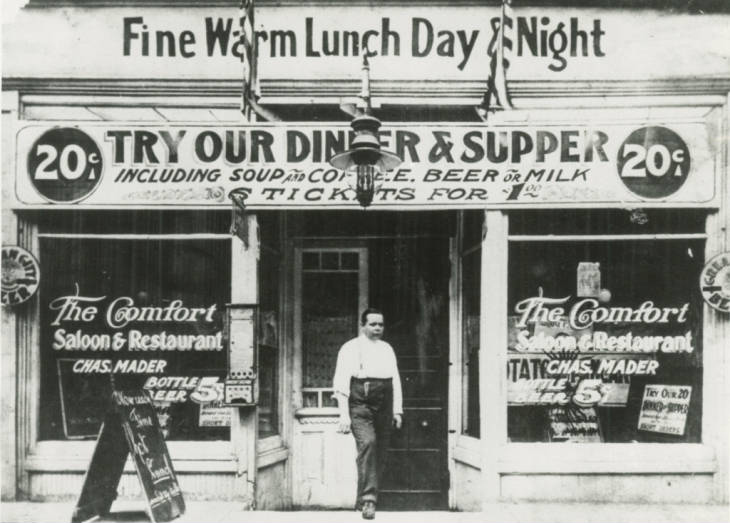

Upon arriving in Milwaukee, Mader is said to have taken a job as a waiter at the Schlitz Palm Garden on 3rd and Wisconsin, but he quickly saved enough to open his own place on West Water Street (now Plankinton Avenue), which he called The Comfort.

Charles Mader outside his The Comfort Saloon & Restaurant.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library)

According to a history on the Mader’s website, "In 1902, A porterhouse steak or half roast duckling dinner were priced at 20 cents, or six for $1. Lunch was four cents, but if you drank two steins of beer at three cents for one stein, or a nickel for two steins, your lunch was free.

"The tables and chairs were wooden and rickety, the walls and bar uneven. The ceiling was tin, a fan provided the air circulation. Often the rugged men who frequently Mader’s became inebriated, and stumbled out."

Added a 1929 Milwaukee Sentinel article, "The Comfort offered a ‘fine warm lunch day and night’ at 20 cents, including soup and coffee, beer or milk. There was a special bargain, six tickets for $1. Men with handlebar mustaches leaned against his long bar, discussing among other things, the ‘high cost’ of $3.50 shoes."

Interestingly, not only is the restaurant absent from the 1902 Milwaukee City Directory, The Comfort is never listed in those books. In fact, the first mention of Mader, who was then living at 652 Market St., is as a waiter at an unidentified business.

From 1906 to 1908, Mader, whose home address changed annually, was listed as running a saloon at 223 W. Water St., The Comfort’s address. In ‘09, interestingly, Mader was listed as living at 221 W. Water (likely above the tavern), but with no mention of a job or business.

From 1906 to 1908, Mader, whose home address changed annually, was listed as running a saloon at 223 W. Water St., The Comfort’s address. In ‘09, interestingly, Mader was listed as living at 221 W. Water (likely above the tavern), but with no mention of a job or business.

Soon – after a brief stint next to the Marshall and Illsley Bank on the west side of Water Street, between Wisconsin and Mason – Mader left Downtown to try his hand at running a business up at 270 Port Washington Rd., at Silver Spring Drive, in what a newspaper report called "a huge frame building."

But life up there must not have suited Mader because by 1911 he was back in the Milwaukee directory.

The tavern on Juneau where Mader operated before moving to the current site. (PHOTO: Courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library)

Back Downtown, Mader operated a saloon at 7th and Juneau, where he also lived, sharing the business with Henry Adler until about 1916, when Mader takes Gustave Trimmel on as a new partner. (Later, the place would operate as Trimmel's Cafe, and, after Gus Trimmel's retirement, it was run by Walter Kirchhuebel for eight years until his death in 1961. His wife Irma collapsed at her husband's funeral and died a week later.)

Interestingly, in 1915, the City Directory listed Mader as living at 7th and Juneau but working as a bar manager at Trimmel’s saloon at 309 3rd St. That same year, Mader became an American citizen and Sam Trimmel, Gustav’s father, was one of his witnesses.

This job also seems to mark Mader’s initial contact with the current site of the restaurant, a tavern building that was erected in 1913.

The saloon replaced an earlier structure with the same address and with an equally illustrious history.

When it was about to be torn down in April 1913, the Sentinel ran a photograph of the exterior and noted, "A landmark at 309 Third Street soon to be razed to make room for a moving picture theater. Victor Schlitz, proprietor of the saloon shown in the view, is a nephew of Joseph Schlitz, founder of Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company, and he has occupied this stand since 1880. Previous to that time it was occupied by the tinshop of George A. Geuder, father of William Geuder, one time a candidate for mayor of Milwaukee and founder of the tin and japanned ware store on St. Paul Avenue and 15th Street, now conducted under the firm name of Geuder, Paschke & Frey."

In addition to running a saloon, Schlitz also operated a wine and liquor wholesaling business out of the same address.

The building’s owners, the Rottman brothers, razed the old building and hired architects Leiser and Holst to draw plans for a new one-story commercial building to cost $4,500. The new place was put up by Williams Brothers carpenters and mason R. Reisinger.

When it opened, saloonkeeper Carl Pelzel ran the place, but not for long, because by the following year, it was already Trimmel’s. By 1918, the names Trimmel & Mader were painted on the sign ouside.

At the dawn of Prohibition in 1920, things changed. Trimmel had moved on and Mader had to find a new focus for his business now that beer was outlawed.

"Mader hung a large sign in his window: ‘Prohibition is near at hand. Prepare for the worst. Stock up now! Today and tomorrow there’s beer. Soon there’ll be only the lake,’ reads the official history on the restaurant’s website.

"When Prohibition struck in 1920 Mader’s wife Celia, saved Mader’s. She turned her full attention to creating the rustic, famous German dishes from her homeland. The sauerbraten, wiener schnitzel and pork shank were called on to meet the challenge and hold the trade without the compliment of the traditional stein of beer."

In 1921, Mader took on veteran neighborhood saloonkeeper Charles Ruge as a partner and two years later, the storefront was altered.

Mader, along with one of his sons and their staff, outside the restaurant, circa 1920s.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library)

More big changes arrived in 1928, as Ruge left the business and, worst of all, Cecelia Mader died, leaving Charles to run the business with their sons George and Gustave.

Cecelia, wrote the Sentinel, "round and slightly taller than her short husband, was the cook who created Mader’s first famous dishes. Charles was his own bartender. He filled many of the old ber stein which still decorate Mader’s restaurant. The price: Two for a nickel."

Together, the two had created not only a well-oiled restaurant machine, but one that was already beloved.

"One glance at the bill of fare will convince any one that this is THE place to eat; this is THE place where once can get a wonderful appetizing German meal, prepared as only mother knew how to do it, and at prices within the reach of all," the morning paper continued. "Mr. Mader prides himself upon the fact that every meal is full, rich and abundant."

In 1931, owner Albert Rottmann expanded the building, creating more space for the booming Mader’s restaurant.

Soon, when Repeal arrived in 1933, things got even better.

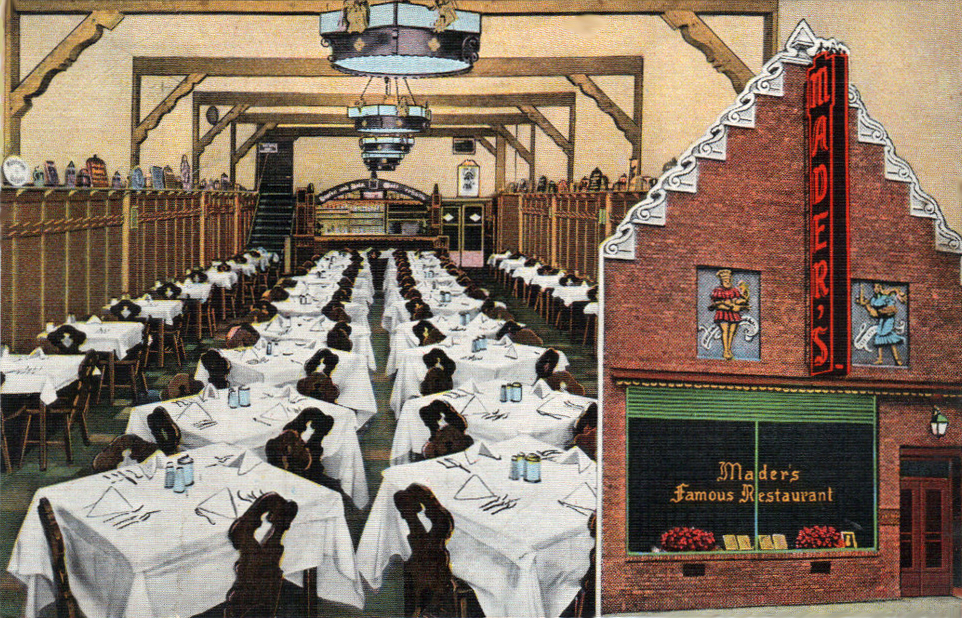

Mader's dining room in 1933.

"(On) that jubilant, cheering night of April 7, 1933, marking the end of Prohibition," notes the company history, "Mader’s was there to serve that first legal stein of beer in Milwaukee and it was announced from Mader’s on the city’s only radio station on that historic midnight."

Added the Milwaukee Sentinel, "Charles Mader, round and hefty in his trim suit, was packing exuberant Milwaukeeans into his German restaurant, sighing at the throngs that couldn’t fit at his big wooden tables. For the hard working restaurant proprietor, the stroke of midnight, when once again steins of beer would be raised in toast, heralded a memorable hour. In the future he foresaw even greater expansion of his business which Prohibition had curtailed in one way but improved in another. When selling liquor became illegal in 1920, Charles Mader turned heavily to food specialties."

Charles Mader and sons with their staff, 1935.

On March 19, 1937, Mader died of stroke while in Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he’d gone to rest after suffering what was described as a "slight heart attack."

Fortunately, he’d groomed his sons to take over and that’s what they did.

"World War II came and Mader’s de-emphasized its German theme but fared well," according to Mader’s own history. "People often lined up hungrily awaiting their chance to indulge in a crispy pork shank, tender wiener schnitzel or tangy platter of sauerbraten. Gus and George celebrated Mader’s 50th anniversary by adding a new dining room, the ‘Jaeger Stube.’"

In 1950 and ‘51, the most visible and enduring changes occurred: Mader hired architect William J. Ames to expand the building and alter the facade, creating the turreted, half-timbered Germanic face that Mader’s still presents to the public today.

Mader’s also grew again, enlarging the restaurant into the adjacent building to the south, adding offices, a service bar, a new dining room and building the marquee.

In 1958, George Mader died, and Gus briefly ran the restaurant on his own.

"In 1961, Gus enrolled his son, Victor, In Michigan State University’s Hotel and Restaurant Management College," says the website history. "After graduation, Victor spent five months working in Europe. In 1964, Victor joined Gus in the running of the family’s Milwaukee restaurant."

Under Victor’s watchful eye, Mader’s added the extremely popular Sunday Viennese Brunch in 1977 and created a small art gallery in the lobby that later moved upstairs to house a multi-million-dollar art collection. It was remodeled into the Tower Galleries in 1980.

Around the same time, the private Baron’s Rhine Stube dining room was added upstairs and panels depicting legends of the Rhineland were added, as were the suits of armor and other antiquities.

In 1988, another new dining room, the Burg Halle, was created during a full remodel.

Since 1996, Mader’s has also operated a catering arm.

And I can assure you that the Knight’s Bar is a great place for a hearty and satisfying German lunch washed down with a crisp and clean Old World pilsner.

I wouldn’t expect that to change anytime soon.

These days, the restaurant is run by manager Kristin Mader, who, as Victor’s daughter, is the fourth generation Mader at the helm ... 117 years after her great-grandfather left Schlitz’s Palm Garden to open a legendary place of his own.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.