The Clock Tower Building, 2266 N. Prospect Ave., at the corner of Prospect and North Avenues is most assuredly an East Side landmark, visible from all directions and across generations who have gazed up at its three faces to synchronize watches or make sure a meeting wasn’t missed.

Folks looking at it recently surely noted the absence of the minute and hour hands on all three clocks. The hands are now back.

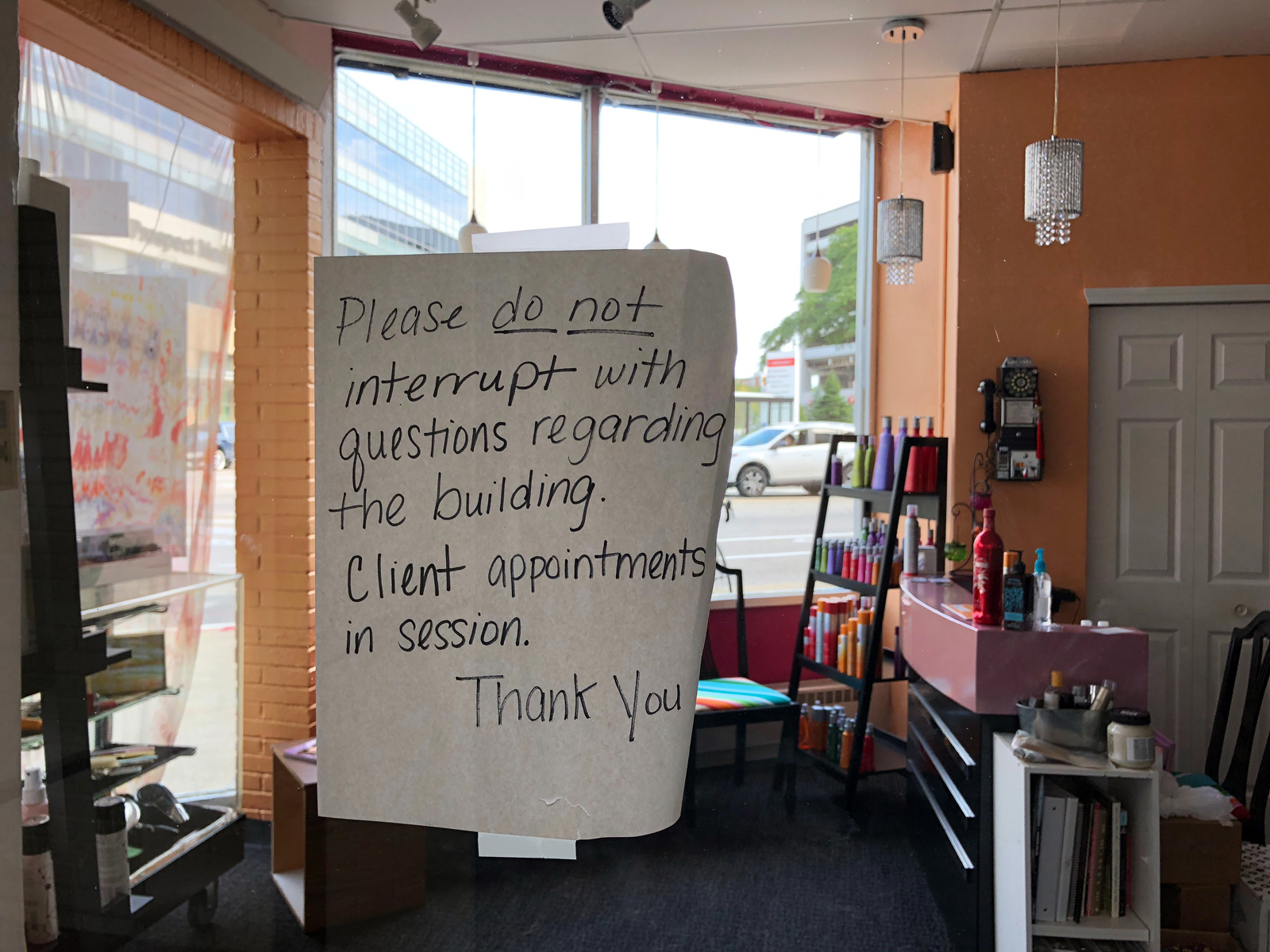

Passersby are so curious about the building and its clock that the salon has been forced to request they don't interrupt haircuts and dye jobs with questions about it.

"I’m having the clock professionally repaired," Carole Wehner of Milwaukee Executive Realty, who has owned the building since 1999, told me when I visited. "It's been repaired several times. We’re refurbishing them, making sure their weight is exact, and weatherproofing them. Because after a hundred years, they kind of get beat up up there.

"It works, but the weight of the hands has to be exact. They all have to work in sync together. If one of them is off a little, it'll drag it, because it's an old fashioned gearbox. It always ran, but one face would be off, and then it would start. Then the other two would start to be off. After a week it would be a half-hour off."

Wehner hired John Witkowiak of Muskego-based Lee Manufacturing Co. to do the work. She said that Witkowiak’s grandfather built the clockworks in the 1960s.

The clockworks are accessed by a door on the roof at the base of the squat tower. From up there, you can see the one side of the four-sided tower that has no clock face.

Interestingly, however, some doors on the roof have extremely ornate knobs and escutcheon plates.

"He took the whole internal part out," she said. "That center circle of the clock comes in. He removed it all from the inside. That was pretty cool. All he does is clock towers and bell towers, probably all over the world, but he happens to be in Milwaukee."

The clock is run by a small clock attached to the works.

The clock is run by a small clock attached to the works.

She recently had the north facade of the building tuckpointed and soon she will have it painted.

"It's going to be basic," she said. "A gray base with terracotta color."

While time has stood still, let’s turn back the clock for a look at the building’s history.

The earliest part of the structure is the section faced in white glazed terra cotta, adorned with Egpytian-themed faces (all the faces are the same except for one) and some neo-Gothic elemets: six floors on the corner and just the first two floors along the north side.

"Glazed white terra cotta ... helped market the structure as fireproof," wrote Ben Tyjeski in his book, "Architectural Terra Cotta of Milwaukee County."

"Corbel tables patterned with rosettes decorate the belt course and parapet. Each face of the clock tower is framed in ogee arches that terminate in fleur-de-lis finials and bellflowers. ... Most compelling are the portraits of pharaohs near the ground floor. There display two kinds of fashions. One has a fan-like crown and lotus flowers and the other has a Nemes headdress and beard. While there is only one left of the latter, originally a second copy was on the northwest corner."

Tyjeski added that the Egyptian motifs were a subtle nod to the building's – and the company's – safety.

"The symbols from ancient Egypt were more than an expression of the contagious admiration for antiquity. Howard Carter's discovery of King Tutankhamen's tomb in 1922 astonished the world. The precious artifacts were so well preserved that the tomb seemed like a vessel for immortality. A warehouse may not be a tomb for a royal family, but its quality could strive for the same type of ambition."

This section was drawn by Chicago architect George S. Kingsley and built by Walter Olflein in 1925 as a new storage warehouse for Coakley Brothers. It was the largest warehouse in Wisconsin when it was built, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society’s architectural inventory.

Among the folks who worked on the building were Froemming Brothers, who did the excavation, Otis installed the elevator, and McClymont did the marble installation. Ritter Brothers were tapped to paint.

The beautiful terra cotta was the work of the Northwestern Terra Cotta Co.

Charles and William Coakley founded the business with $165 in 1888, along with another brother, George, who later left the business, but it started out as the Lightning Express Messenger and Express Service, which moved freight to and from train cars, as well as providing messenger services.

When they started work on the Clock Tower Building, the Coakleys divested themselves of their Downtown restaurant, called Jersey Lunch, at 6th and Wisconsin, selling it to William Hill.

According to a report in the Milwaukee Journal, "Their restaurant, one of the biggest in the city, had been controlled by Coakley Bros. for 15 years ... (the brothers) decided their warehousing operations required all their attention. Warehouse now in course of erection at North and Prospect Avenues will be completed in December."

When the Clock Tower Building opened in April 1926, the Sentinel raved.

"A storage warehouse which is more than the usual bleak cube of windowless walls is one of the architectural features of the east side since the completion and opening of the new building of Coakley Brothers at North and Prospect Avenues," the paper exclaimed.

"Fronting on the principal arterial thoroughfare of the East Side, the tower attracts the attention of thousands of motorists daily. A conspicuous clock in the tower is used by hundreds to check the accuracy of East Side clocks and watches. Erected at a cost of $350,000, the building incorporates all features of modern storage design."

Located on the first-floor was Northern Motor Sales, which inked a five-year lease for a 100x140-foot showroom with offices. A 100x25-foot stockroom was located above, and freight elevator to move the autos up and down was installed. It’s still there today.

At the dealership in 1928, deputy marshall William R. Phillips – who according to one account, "gained some experience in the art of ballyhoo by hawking hot dogs at carnivals years ago" – auctioned off eight cars that had been confiscated by Prohibition agents.

The building, in a photo taken after the expansion. (PHOTO: Courtesy of Coakley Brothers)

Later, the space was home to Studebaker Sales Co.

Business for the Coakley Brothers was good. Two days before the paper reported on the opening of the new warehouse, it wrote, "Coakley says that in 39 years’ experience he never has stood upon the threshold of such a large moving year as this promises to be. ‘We’re loaded way up with orders for May moving and so are other firms,’ he said. City has 350 moving companies."

By 1927, when they were ready to expand the Clock Tower, the Sentinel estimated the Coakleys’ "total net investment" at about $1.5 million.

Coakley hired hometown favorites Eschweiler & Eschweiler to design the expansion, which basically filled in the open part of the building. It’s the part that you can see now along North Avenue, made of brick.

Before the Eschweilers drew the addition to the Clock Tower, they were busy at work on a second iteration for the Coakleys, to be located at 37th Street and Wisconsin Avenue. This building (pictured at right in a photo courtesy of Coakley Brothers) also still stands.

In July 1927, the Sentinel reported that the West Side Coakley building would cost about $200,000.

"It will be similar to the one recently completed at North and Prospect Avenues. A distinctive feature will be a tower. Plans ... call for a structure 150 feet long, 75 feet wide and 85 feet high. Besides storage facilities, the building will contain and automobile showroom on the first floor. The permit has been taken out.

Four months later, the Journal chimed in that the "new Coakley warehouse at 37th and Wisconsin costing $275,000 will have a ‘ninth story’ in the roof on which automobiles will be parked. They will be taken up on elevators. ... The building is being constructed so that it could be used for light manufacturing or as a garage. On the first floor there is a large showroom, the ceiling of which is just below the third floor, the room having a mezzanine floor."

In June 1928, the expansion of the Clock Tower Building was announced.

In June 1928, the expansion of the Clock Tower Building was announced.

The new construction would add 250,000 square feet across five additional stories and cost about $60,000.

In September 1929, the Coakleys told the morning paper, "we have never experienced such a rush as we had this Saturday. The last three days have been very busy but in 39 years Saturday was our busiest day. We had 14 trucks out and kept busy."

Soon after, the crash on Wall Street would bring hard times for all, including the Coakleys.

In 1933, they partnered with Allied Van Lines, boosting their ability to ship goods long distances, and in 1952, the next generation took over the business, which later splintered into the competing Coakley companies that survive today in Milwaukee.

In 1959, the company sold the Clock Tower Building to George Bockl and he remodeled the warehouse into offices.

By the time Wehner bought it – from Bill Becker, who, she says, owned it briefly – it was in need of love.

"He did the mechanicals," she recalled. "But the place was 60 percent vacant when I got it. Shag carpeting every room. It was dirty. We went through and just started redoing offices and fixing it up. And now, there's over 60 tenants in here."

Hiding in the basement are some cool old signs (including a Suburpia one that hung outside for many years), as well as a former electrical substation that's locked up tight and periodically gets an inspection visit from We Energies.

Now that the clock is back up and running, allowing East Siders to check the accuracy of their clocks and watches, the building – which has at least two clocks and two images of the clocktower in its intimate lobby – continues to be worthy of its name.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.