The coronavirus pandemic has changed our everyday life, but it doesn't need to change who we are. So, in addition to our ongoing coverage of the coronavirus, OnMilwaukee will continue to report on cool, fun, inspiring and strange stories from our city and beyond. Stay safe, stay healthy, stay informed and stay joyful. We're all in this together. #InThisTogetherMKE

Announced in September, the Mandel Group’s $150 million Harbor Yards mixed-use development with a hotel, apartments, office space, public green space and more will remake the south bank of the Milwaukee River as it heads out to the lake.

It will also bring a vibrant new life to a stretch of South Water Street that has long been an industrial zone.

One casualty of the 4.25-acre project is the old grain elevator that goes by a variety of names, reflecting the convoluted history of many Milwaukee maltsers over the decades.

A rendering of the future Harbor Yards. (PHOTO: Mandel Group)

Mandel Group hopes to have the silos demolished this year, but plans to save the foundation, upon which it will build a 10-story office building. Next door will be a residential building and just north of that, a hotel is planned.

Though the developer hasn’t yet sought bids for the demolition, Elizabeth Adler says the previous owner – Kurth Malting – did so a few years ago and they ran upwards of $2 million.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

When the current elevator was erected by the Burrell Engineering and Construction Co. in 1932, the company was called Zinn Malting.

Born in Milwaukee to German immigrant parents, Albert Zinn got his start in grain working as a bookkeeper in the Nunnemacher flour mill in 1877, but six years later, he and his brother were partners in the Zinn Malting Co., which Adolph opened in 1875 on the site of the original Schlitz Brewery at 5th and Juneau.

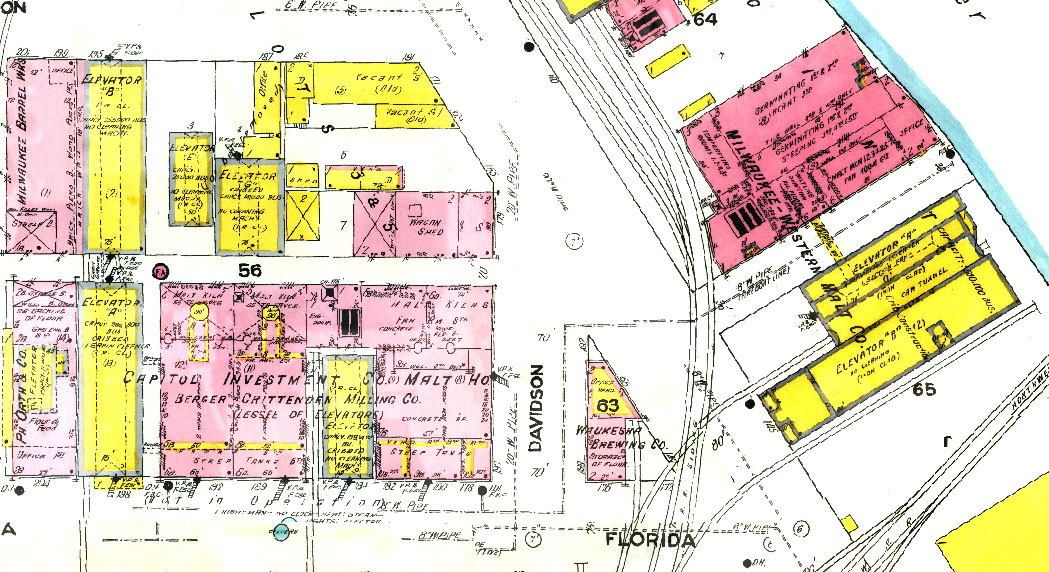

The 1910 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows the complex and those of nearby maltsters, too.

Merging with Asmuth Malt & Grain in 1892, the new company – Milwaukee Malt & Grain – was sold five years later to American Malting Co., where Zinn was assistant general manager for three years before joining the Milwaukee-Waukesha Brewing Company briefly. He later spent a little time as a general manager at Miller Brewing.

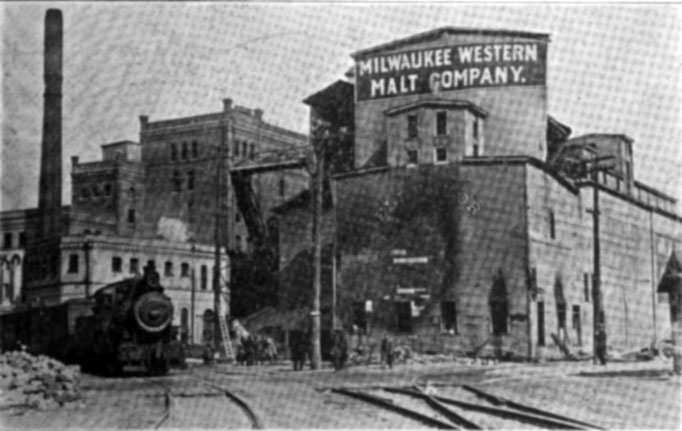

But by 1903, the Zinns partnered with Charles Manegold Jr., who had sold his Milwaukee Malting Co. to American Malting in 1898, to create a new maltster called Milwaukee-Western Malt Co. and the new company built its headquarters on the west side of South Water Street and its malt house and grain elevator on the east side of the street, along the river.

A 1908 advertisement.

Back then, elevators were often built of wood and clad in corrugated iron, and tended not to last very long.

In fact, the book "Beertown Blazes" has an entire chapter on the seemingly endless stream of grain-related elevator and building fires, at breweries, maltsters, flour mills and other related businesses.

"Probably nowhere else in local history is there a similar record of every single major building of its type having been destroyed by fire," noted the authors James S. Haight and R. L. Nailen.

The malster's offices across South Water Street.

"Fire hazards abounded in these structures. Overheated shaft bearings, and friction sparks in the machinery, were later joined by electric lights and wiring. There were no sprinklers or alarm systems as a rule. Electrical storms were a danger, too. But the worst hazard of all was the constant danger of spontaneous ignition followed by dust explosion. ... Grain dust explosions were a factor in many such fires.

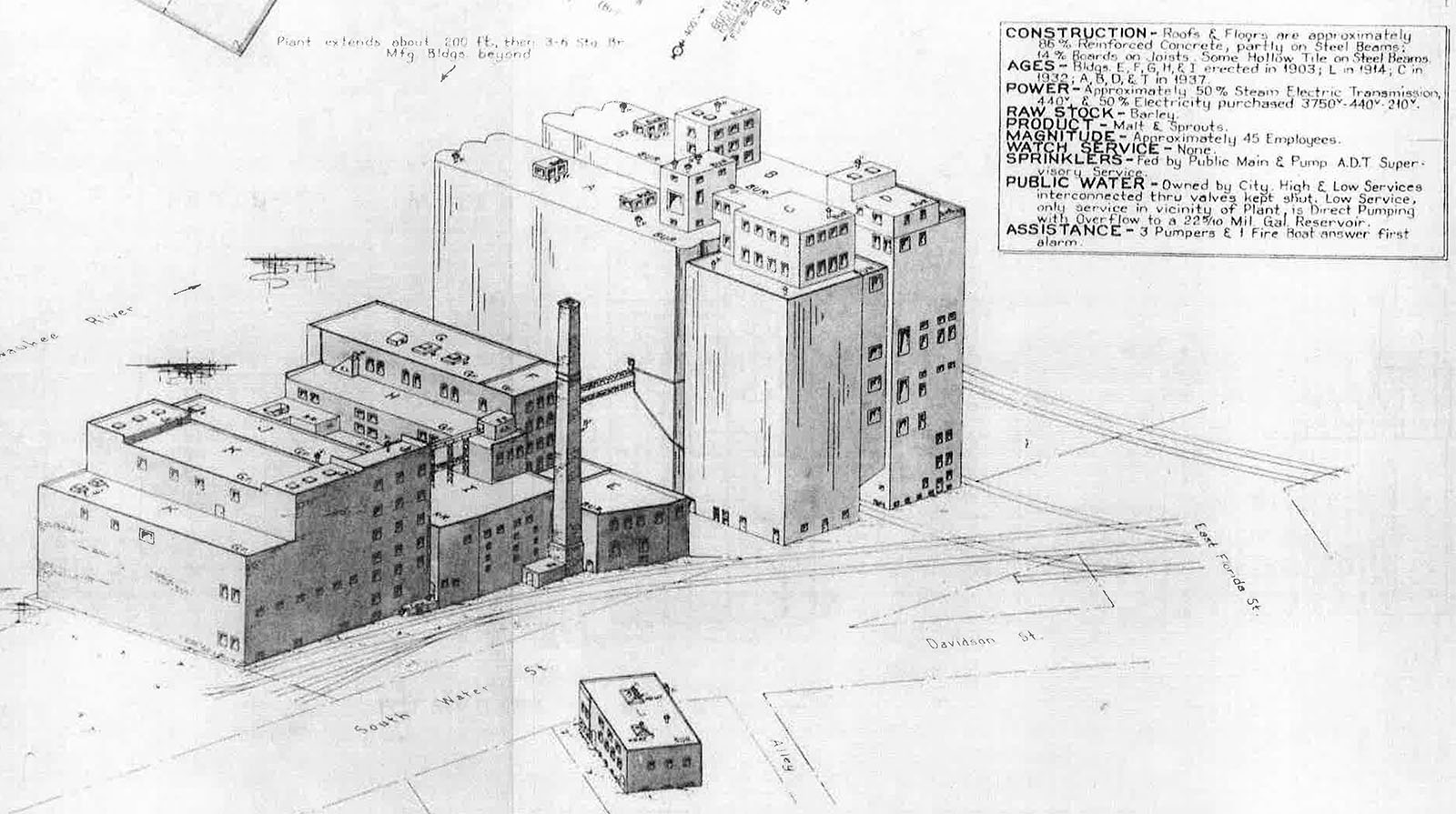

The complex as it stood in 1938.

"In the memory of south side firemen 50 years ago (in the 1920s), ‘Grain elevator fires were our biggest problem. And we had to keep going back afterward – stand outside and pour on water. Those sheets of corrugated iron kept falling off the walls; they could slice a man in half. At the Kneisler elevator on Florida Street (December 1923), we had to work at those ruins for three months.’"

One such fire burned so brightly that the flames could be seen reflected on the water by sailors 30 miles out. At another, the glow was visible in Chicago. One lone wooden elevator survived into the modern elevator, the one at JM Riebs Grain and Malt Co. on 29th and Pierce. It, too, burned in the end, in 1971.

By the time Albert Zinn died in 1919, his family’s grain elevator had suffered at least two major fires – in 1916 and 1918 – according to "Beertown Blazes."

After the 1916 fire.

That would explain why the company, which later took the name of its co-founder, becoming Zinn Malting Co., built its new $40,000 grain elevator of concrete in 1932.

For a time, the elevator was owned by Kurth Malting (later Fleischmann Kurth Malting), which was started by the same family that created Kurth Brewery in Columbus, northeast of Madison.

Interestingly, the 1910 Sanborn fire insurance map for Milwaukee shows an elevator (marked Elevators A and B) on the exact footprint of the current structure, with markings that suggest the elevator was built in three segments, with a fourth part added after 1910, and a rail car tunnel passing through the center of the ground floor.

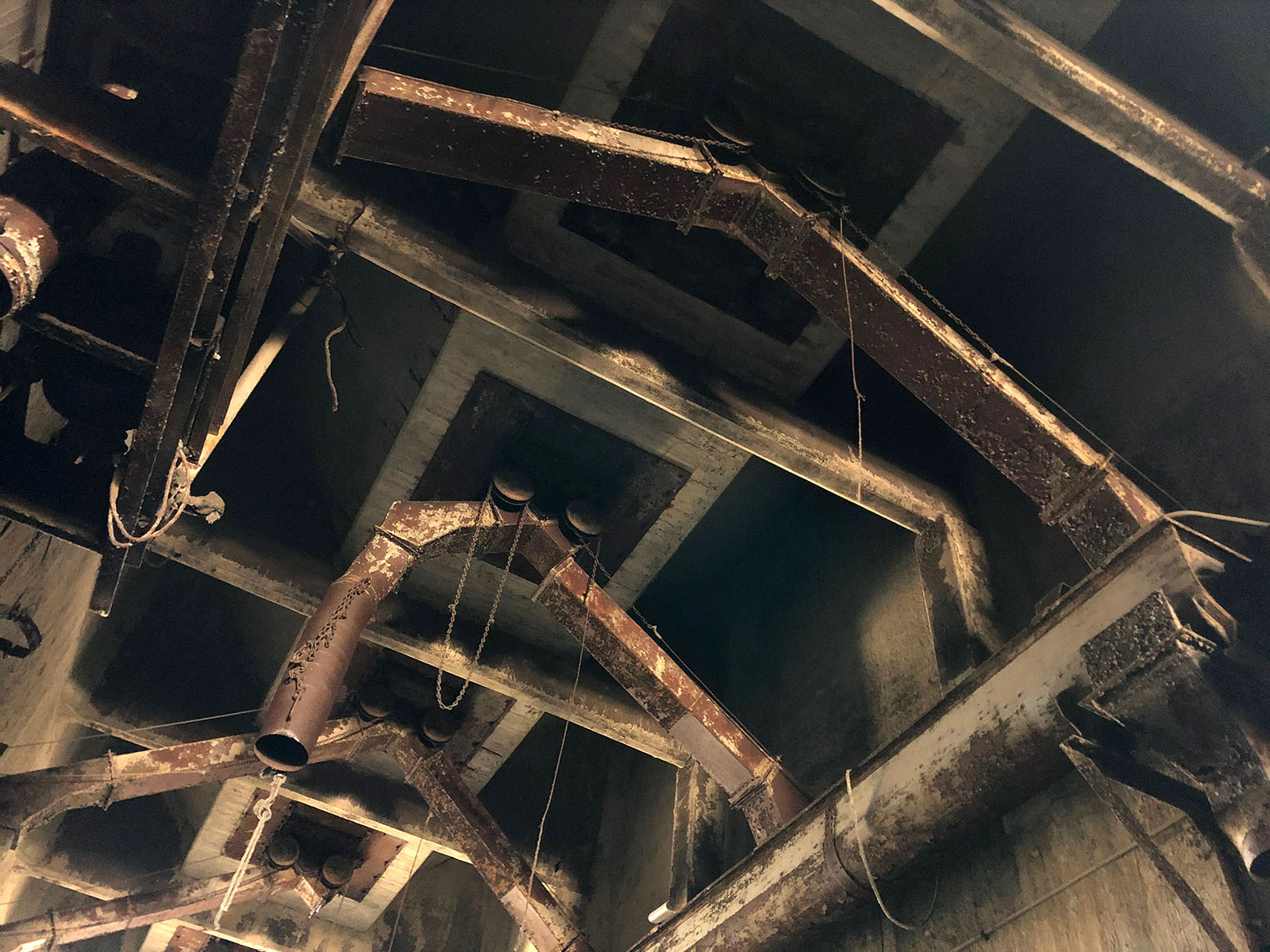

Above and below, two views inside the rail car tunnel.

Those segments can be seen in aerial views of the current building (and there’s a rail tunnel in the same spot), suggesting at the very least that the 1932 mimicked a predecessor and that, potentially, the 1932 building was not built from the ground up but perhaps put concrete around an existing structure.

A Milwaukee Sentinel article of Aug. 14, 1932 would appear to put any doubts to rest, however.

As the whiff of repeal of Prohibition grew stronger in the air, the paper wrote, "The courage to build Milwaukee’s newest $150,000 structure found its origin in the firm conviction of the building that the manufacture and sale of beer and light wines will be legalized in this country within 18 months.

"The building – a huge grain and malt storage elevator at 338 S. Water St., believed to be the heaviest concrete structure in the state – has just been complete for the Milwaukee Western Malt company, whose president, Walter A. Zinn (Adolph’s son), declares he was influenced to great extent by the probability of modification of the Eighteenth Amendment."

The paper reported that the 165-foot-tall elevator – designated Grain Elevator C – was made entirely of reinforced concrete and sat upon a foundation of steel weighing 30 tons. The 10-story structure could hold 300,000 bushels of grain – wheat and barley – and "each process operates strictly on a gravity principle."

Interestingly, 1910’s combination Elevators A and B had a capacity of 500,000 bushels.

"I am positive beer is on its way back," Zinn told the Sentinel. "I think we will see beer legalized by the fall of 1933 and I intend to be ready to handle grain and malt in the most efficient and economical way possible."

He was so intent that Zinn designed the elevator – the company’s third to be built on the site, the paper noted – himself and had it "rushed to completing in three weeks."

That’s not a typo. Three. Weeks.

Overseen by architects/contractors Klug & Smith, 180 men toiled day and night to allow the building to "grow 16 to 20 feet in 24 hours."

The 35 Allis-Chalmers employees that had been on the job since the previous week expected to be done installing all the electrical workings of the elevator in time to have the structure "completed, ready for use by Aug. 20."

The reason why the footprint of the current elevators matches that of the earlier ones is because Elevator C was built in the vacant corner of the land, with the old elevators wrapping around it like an L. In 1937, the old elevators were demolished and replaced with new concrete elevators A and B and an Elevator D.

"More than 60 percent of our malt is now consumed by cereal companies at Battle Creek, Michigan, and breweries here in Milwaukee," said Zinn, whose family had, by then, been in the malting game in Brew City for 65 years, in that 1932 article. "A great deal also goes to yeast manufacturing concerns. The real demand will come in the fall of 1933, I believe, with the return of beer."

Zinn was right. Prohibition was repealed in 1933 and Milwaukee’s breweries – as well as those across America – were back up and running ... at least some of them. The 18th Amendment did serious damage to the brewing and distilling industries in the country that would endure for decades to come, partnering with consolidation to wipe out small producers until the craft boom brought both industries back.

In 1955, Zinn Malting, which had about 40 employees (about five fewer than in 1938), was purchased by Kurth Malting – which operated a plant on 43rd Street, near one now owned by MaltEurop – and shut it down.

Walter Zinn died at the age of 81 in 1957, leaving more than one towering monument on the landscape. Since 1911 he’d worked diligently on building a dollhouse for his daughter and every year, the creation is dolled up (sorry) for the holidays and put on display at the The Washington County History Center in West Bend.

The day I climb to the top of the grain elevators, I meet Jerry Guyer, who runs a diving, boat storage, charter and dock business next door, on the site of the former malt house. He’s been there 22 years, and will soon have to leave to make room for the new development (he’s looking at a site in the Menomonee Valley, not too far away).

These three City of Milwaukee photos show the complex in 1994,

including the connection between the silos and the malt house.

"It's been closed the whole time (I’ve been here)," he tells me as we sit outside in his van on a chilly day, "I've always just leased it.

"Between 10 and 15 years ago the city came and said, ‘Well, you can't have all these broken windows,’ so the attorney for the Kurth family said, ‘Jerry, we need you to cover all the windows.’ I said, ‘We don't do that kind of work.’ ‘But you're the caretaker there. There is nobody else that does it either and it'd be too expensive for somebody else.’

"So they paid us for time and materials and it took us the whole summer, because you can see how many windows, and then there's on the top, there's three stories of buildings on the top. So it's pretty big."

Though Guyer remembers the malt house – he grew up in the neighborhood and his business was a little further up South Water Street before it was here – it was torn down before he moved to the site.

Though he boarded up the windows on the silos, he’s never occupied them, he says.

"We put stuff in there over the years, in the alleyway in between," he says, referring to the train car tunnel. "There were tracks right here where we're standing, too (just north of the silos). We had a man stop by one day who said he was working for the railroad when they used to take the cars in there and dump the grain. In fact, he said they just rolled them in. There was enough of a grade that they'd roll right in there on their own. Then they had to be pulled back out."

Guyer says the biggest challenge he’s faced as caretaker of the elevator has been vandalism and trespassers.

"Yeah, trying to keep them from getting on top of it," he says. "We've been diligent and we're here every day. There was a fire escape on the backside where the last 20 feet you could pull down a section. We took that off early on. Then we realized the kids would just stack up stuff we had and get up there. So we took another 20 feet off.

"We kept taking more off, more off until we couldn't reach any higher to take any more off. And still they stole extension ladders from the project across the river, carried them around the bridge – I don't know how anybody didn't stop them – and put these 40 foot ladders up so now we had to take another 20 feet off. I wouldn't get on that fire escape even if the building was on fire. It's 100 years old."

Then he tells me about the big painted graffiti that was once near the top on the north side of the elevators. It read, simply, "FCR," which was there when he arrived more than 20 years ago and which is still there, but now hidden by a big Mandel banner advertising the new development.

"We deal with the police department a lot because of the work we do on the river, and we actually know the gang squad people," Guyer says. "They came over one day and I said, ‘Look at that up there.’ He said, ‘We know what that is. That's the Fat Chicks Rule gang.’

Up on the roof (above and below)

"If you look at it, that's really an impressive thing. It wasn't done from the ground reaching up. It was done with them hanging over the edge with a roller on a long stick. You'd have to put pressure on the roller (while you lean). Can you imagine the nerve?"

Well, I couldn’t imagine it and when I finally get to the top of the silos, about 12 stories up, I find that there’s no way I would even get within a couple yards of the edge, which has no barrier of any kind. It’s simply an edge and a sheer drop. How anyone had the fearlessness (or deathwish) to paint those three outsized letters is simply beyond my imagination.

However, I wasn’t afraid to go inside. We started inside the train car tunnel, which still has a lot of Guyer’s boats stacked up inside, and walk through a door at the base of the north silos to get to the metal stairs that reach all the way to the roof, occasionally with crossovers to the south silos.

Stepping inside the doorway, the stairs are on the right, but on the left is an open single-person "elevator," the likes of which I’ve only ever seen in parking structures for valets.

But those (see the example in the video below) were typically in tubes and only a few stories high. This one was completely open, with a rail to stand on and another to hold on to and 12 stories tall.

Clearly, between this and the FCR there are people far more comfortable with heights than I am.

As we ascend, there are spaces with rusting equipment that makes me wish I’d brought along Bob Wright from Malteurop so he could identify everything. There were also long troughs with horizontal augurs used to move grain along.

And as at the Pabst silos I visited last year, there were many holes in the floor – mostly, but not all, with caps – offering looks (or a deadly fall if you’re not careful) into the storage spaces for grain.

All the way at the top, there are three stories of small buildings, with a variety of rooms. Some are empty, some have more equipment and one is a penthouse with the motor for the (non-working) elevator.

The views up here are as amazing as you’d expect, looking out over the Hoan Bridge and Jones Island, north toward Downtown, south toward Bay View, west of Walker’s Point and clear out to Holy Hill on a clear day.

On the way back down, I take a moment to stop and imagine the place up and running in Zinn’s day, with the smell of fresh grain mingling with the scents from the malthouse next door – cucumber as the barley germinates, a smoky nuttiness as it dries in the kilns – and the hubbub of workers manning the machines and ascending and descending that terrifying lift.

There’s no doubt that the Mandel development, with its apartments, hotel rooms and offices will be a boon to the city and to this neighborhood, but, still, I’ll always spare a thought to the malting history that lived along the Milwaukee River on this site.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.

%20copy.jpg)