The public announcement that the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra is working to renovate the former Warner Grand Theatre, 212 W. Wisconsin Ave. – an idea that’s been swirling around, on and off, since it was first floated in 2001 – is big news.

It’s big news for the MSO, which says that having its own home would allow it to grow.

It’s big news for Marcus Theatres, which I’d think would be happy to move on from the theater, which closed in 1995 and has been moribund ever since, staring at us as a constant reminder that Milwaukee’s once, ahem, grand Downtown movie tradition is as faint and flickery as an old talkie.

It’s big news for Westown, which could use a jolt across from the struggling mall.

It’s big news for me, because I have many fond memories of the place – and judging from reaction to this story, you do, too.

The history

What many of us remember as the two-screen Grand was built as a huge single-screen theater by Warner Brothers in 1930.

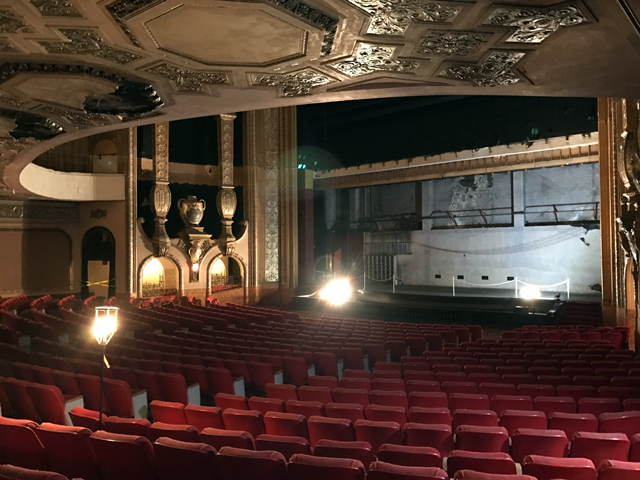

Designed by architects Rapp and Rapp – who had drawn the Uptown four years earlier and the Modjeska on Mitchell Street and the Wisconsin on 6th and Wisconsin in 1924 – the Warner could seat just shy of 2,500 patrons in its stunning French Renaissance theater.

Designed by architects Rapp and Rapp – who had drawn the Uptown four years earlier and the Modjeska on Mitchell Street and the Wisconsin on 6th and Wisconsin in 1924 – the Warner could seat just shy of 2,500 patrons in its stunning French Renaissance theater.

Brothers Cornelius and George Rapp hailed from Carbondale, Illinois, but worked in Chicago, where they made their names building a slew of gorgeous theaters – some of which you can still see now, like the Chicago Theater on State Street, the Oriental Theater and Cadillac Palace Theatre on Randolph, the Riviera on Racine and the Uptown on Broadway.

These guys knew a thing or two about designing theaters. It’s interesting the way they blended styles at the Warner, which, despite its elaborate retro French vibe in the theater itself, has an Art Deco lobby that relies on a much simpler, cleaner approach. The exterior of the building is also executed in the Moderne style that was all the rage at the time.

An advertisement for the Warner boasted that "within the dreamlike portals of this enchanted playhouse, is imparted a breath of the medieval French and the ultra modernistic where patrons will glory in the beauty of its inspiring environment."

The brothers used the same approach for Chicago’s Oriental, which draws on both extravagant European court decor and Art Deco styles – with a dash of Eastern flavor in homage to the name. The Warner was apparently quite similar to the design the brothers did in 1927 for the Portland Publix Theater (later the Paramount and now the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall).

The theater boasted a 28-rank Kimball pipe organ. That organ – restored by the Kimball Theatre Organ Society – can now be seen and heard at the Oriental on the East Side.

According to Cinema Treasures, an encyclopedic online cinema history resource, the Depression did cause Warner Brothers to scale back on some – but not all – features.

"The blueprints show that provision was made for a motorized orchestra pit elevator, but along with other amenities, it was omitted as a cost conservation as the Great Depression made itself felt. They did find money, however, for a display fountain in the basement lounge, as well as on the next three levels above."

The exterior of the 13-story office and theater building is pure Deco, with dark polished granite and hints of pink on the first-through-third floors, narrowing in steps on the fourth and fifth. Above that, in the four center vertical rows – or Empire Lines – each window's capped with a decorative cast metal panel. Look closely and you can still see the hardware that held the old vertical sign between the fifth and sixth and the eighth and ninth floors.

Unsurprisingly, the opening of such a place in Milwaukee at the time drew much attention.

Unsurprisingly, the opening of such a place in Milwaukee at the time drew much attention.

"In 1931, as if to defy the Depression that gripped America’s purse strings, the grandest of Milwaukee’s movie palaces, the Warner, opened on the site previously occupied by the Butterfly Theater," wrote Larry Widen and Judi Anderson in their book, "Silver Screens."

"Opening night at the $2.5 million ($34.4 million today) Warner Theatre was an extravagant, sold-out affair attended by thousands," Widen continues. "Milwaukee photographer Albert Kuhli was hired by Warner Brothers to photograph the inaugural festivities. Kuhli recalled how he was told to ‘make a lot of noise’ and explode flash powder at various intervals, even if he was not really taking a picture, to add to the glamour of the evening.

"Newly arriving guests were greeted by 44 blue-clad ushers who provided curbside service and assistance into the foyer, where a classical string quartet played. The program for the evening began with the 'Star Spangled Banner,' followed by an address by Mayor Daniel Hoan. Next on the bill was a newsreel, two comedy shorts, and a solo performance by Giovanni Martinelli, leading tenor of New York’s Metropolitan Opera Company. The evening’s feature film was ‘Sit Tight,’ a comedy starring Joe E. Brown."

The new theater was to be the shining star, the jewel in the 10-theater Warner crown in Milwaukee, which also included the Venetian, Egyptian, State, Downer, Kosciuszko, Granada, Riviera, Juneau and Lake Theatres.

Widen and Anderson also noted what it meant to work at a place like The Warner, quoting veteran projectionist Gilbert Freundl:

"When you worked at the Warner, you weren’t allowed to make mistakes. They expected the best. You learned your craft in one of Warner’s smaller houses, like the State, or the Downer, out in the neighborhoods, and slowly worked your way to Downtown. You had to prove yourself before working there."

The Warner, however, would be the last for a while. While a couple more would trickle through, Widen and Anderson say that the Warner was the "beginning of the end of theater building in Milwaukee. ... The Great Depression effectively ended Milwaukee’s seven-year theater construction boom."

But the Warner would remain active for another 60 years. According to "Silver Screens," Marcus bought it in 1964 and, two years later, renamed it the Centre. In 1973, a ceiling was built about halfway up the theater – along the bottom of the balcony – to create two cinemas: one on the main level and one that used the balcony seats as an upper theater. That divider has since been removed.

In 1981, artist Richard Haas painted a mural on the side of the building that depicts the Pabst Building, which was soon to disappear from the Downtown landscape.

In 1982, the theater was renamed The Grand in conjunction with the gala opening of the sparkling new Grand Avenue Mall across the street. Just 13 years later, in June 1995, the doors were locked, and the story appeared to end there.

When I moved here in 1983, it was the first place I saw films. I’ll always remember it as the place I saw a double feature of "48 Hours" and the then-new "Trading Places." Where I stood in line to see Prince’s exciting "Purple Rain." Where I saw "Dune." And "Beat Street" and "Breakin'." Where I hung out with Grandmaster Melle Mel and the Furious Five before and after their performance there. The last time I was in the building was to see a press screening of a film in the basement screening room sometime in the early 2000s.

Like a lot of you, I’ve been eager to see inside again. This week, thanks to the MSO and Marcus Theatres, I finally got the opportunity.

Enter the MSO

Though in recent years there had been at least one initiative to get the Warner Grand Theatre opened again, it would appear that the MSO’s plan has the longest, strongest legs and offers the most hope for fans of this place.

"Here we are 15 years later, hopefully going to see this thing come through," says Mark Niehaus, president and executive director of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra. "The stars are kind of aligning for all this. It’s really neat."

A key driver for the project is the fact that the MSO currently performs at the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts, which is a heavily utilized facility.

"I don’t fault the Marcus Center at all," says Niehaus. "They should be doing Broadway. That’s part of what our city should have: great Broadway. We should have great ballet. We should have great opera, and we should have a great symphony. Trying to think that all four of those things should co-exist in one room, Uihlein Hall ... we’re busting at the seams.

"We do enough that another building could live off of us."

In recent years, there had been talk of a new MSO performance space as part of the upcoming Couture development at the lakefront.

"That was great because it started the conversation," Niehaus says. "If we could’ve raised the money, we would’ve done it. I thought it was a pretty thoughtful design. The idea of a condominium symphony hall attached to somebody else’s building, and they heat it and clean it for you. That was very interesting to us. That, however, still would’ve been more expensive than what we’re doing here.

"I love the idea of the symphony activating the lakefront as a destination, I think even more the idea of the symphony activating West Wisconsin Avenue as a destination. We talk internally about our triple bottom line here. We’re rationalizing the symphony’s business model, we’re saving a historic gem and we’re activating West Wisconsin Avenue. All in one shot. That’s the kind of case you want as a fundraiser. Maybe you’re not so into the symphony, but you really love architecture and you really love economic development Downtown. Boy, have we got a project for you."

Inside the theater

Stepping into the lobby is a revelation. All glass and bright aluminum Art Deco decoration, this is clearly the entrance to a classic movie palace. To the right is a long staircase up to the balcony. Just a little further in is another one and behind it the stairs to the lower level restrooms. Further along on the right are more entrances to the theater – a couple old phone booths, the lights of which turn on automatically when you shut the doors – and to the left a pair of men's and women's lounges.

Inside the theater itself, there is, again, decoration everywhere. Panels painted by Chicago's Louis Grell depict idyllic scenes – a man playing the flute, a man pushing a woman on a swing, a woman playing a long-necked lute, a man lounging and reading a book. Every surface is covered, and your eye hardly knows where to go first.

In front of the stage is an orchestra pit, the border of which is traced with a low rail. The back of the stage wall is the exterior wall facing 2nd Street. There is no backstage because this was built as a movie house.

The room is extremely live, acoustically speaking.

"The symphony built a plywood stage in 2001 and did acoustical testing in here; I actually was playing in the orchestra at that point, and I remember playing on the stage and the sound was amazing," Niehaus recalls. "We know it’s amazing."

Fortunately, Marcus had the foresight when splitting the theater in two to not do much damage, and what damage has been done can likely be repaired according to Niehaus. Changes to the front of the balcony appear to be the biggest issue, but Niehaus believes that can be restored. Most other changes, like removing the projection booth added on the first floor, can be done without any damage to the original decoration.

Whether or all of this will be restored and renewed remains in question, but it sounds like the prospects for the theater's revival are good. The MSO is in the midst of a campaign to raise the $120 million it estimates would be required to buy the building and prep it for re-opening (that figure, says Niehaus also includes an endowment and eliminating a pension liability) and Niehaus says it has already raised more than half that amount.

The MSO has brought in Conrad Schmitt to discuss restoration possibilities and is working with Kahler Slater Architects – which initially became involved in 2011 – on the plans, which include making the building ADA accessible.

What this means for the MSO

"The MSO is the only major orchestra in the United States without control over its own performance venue," says Niehaus. "The symphony hall in St. Louis is a Rapp & Rapp theater. Heinz Hall in Pittsburgh is a Rapp & Rapp theater; the Warner Theatre in Erie, Pennsylvania, is the same thing. So we're not the first to do this. It's kind of a no-brainer. This thing has been sitting here just waiting for us."

Having its own home would allow the MSO to create new sources of revenue, Niehaus says, from things like facility rental fees – something it has discussed informally with The Pabst, Riverside and Turner Hall operators – and concession sales.

"There’s absolutely no reason those (Pabst) guys can’t be in here on the nights the symphony aren’t playing," Niehaus says. "They’ve developed an amazing business model, and it’s at capacity. We don’t have an agreement, but there is interest by them and others to fill our empty dates."

The Symphony estimates it could boost its revenue by as much as 60 percent. Plus, the orchestra would have complete control over its own scheduling, something it does not have in its current home, the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts, which it shares with a number of other arts groups and events.

The tower above the theater is empty and has long been so, according to Niehaus, who says that part of the building isn't the focus for the MSO, which might consider moving its offices there, but that's a discussion for later.

"I believe it's been empty just about as long," he says. "It's class B office space, and there's a glut of that in Milwaukee. We don't have any income in our revenue model from the tower. The last money we will invest will be for administrative office space."

Considering the impact it could have in its immediate neighborhood, too, in terms of restaurants and the like, I think it’s an exciting idea. But, I admit, what I’m most excited about is the preservation of Milwaukee’s last great movie palace, and of memories we all made there.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.