Eight years ago, I wrote about the history of Milwaukee's Gaenslen School, and of its predecessors, open-air schools that almost created outdoor classrooms, albeit with ceilings and some wall structure.

The flow of fresh air helped make it possible for ailing children to be together more safely during a time of pandemic infectious disease.

Today, I'm resharing this story below in its entirety, because the open-air classroom just might make a comeback as school districts consider ways to educate children in the coronavirus era.

To read more about this idea, check out this recent Ginia Bellafante article in The New York Times.

Though Milwaukee's Gaenslen School – which has a special needs population approaching 50 percent – is named for Milwaukee's first orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Frederick J. Gaenslen, an argument could be made that it should have been called Potter School.

Then-MPS superintendent Milton Potter was the force behind the first classes held specifically for children with disabilities in 1913 (the district also had a school for the hearing impaired). Though that program was short-lived, Potter was determined to help educate students who couldn't physically get to regular classes.

He next started a system of providing instruction in the homes of children. By 1917, MPS – with Potter still at the helm – built the Lapham Park Open Air School at 8th and Walnut, next to Ninth Street School (currently the site of Elm Creative Arts, Alliance School and Roosevelt Middle School of the Arts). According to a district publication from a decade later, the school, which had an enrollment of 132, "provides education for weakened children in a wholesome atmosphere."

As the name implies, the building's many windows could be flung open to provide a constant stream of fresh air – such as it might have been in early 20th century industrial Milwaukee – which was recommended for many ailing children, especially those suffering from tuberculosis, which was rampant in the early decades of the 20th century.

Cots were provided in classrooms to, in the words of a newspaper photo caption of the day, "make children comfortable."

The idea for these schools originated in Germany and the first U.S. examples opened in Rhode Island in 1907.

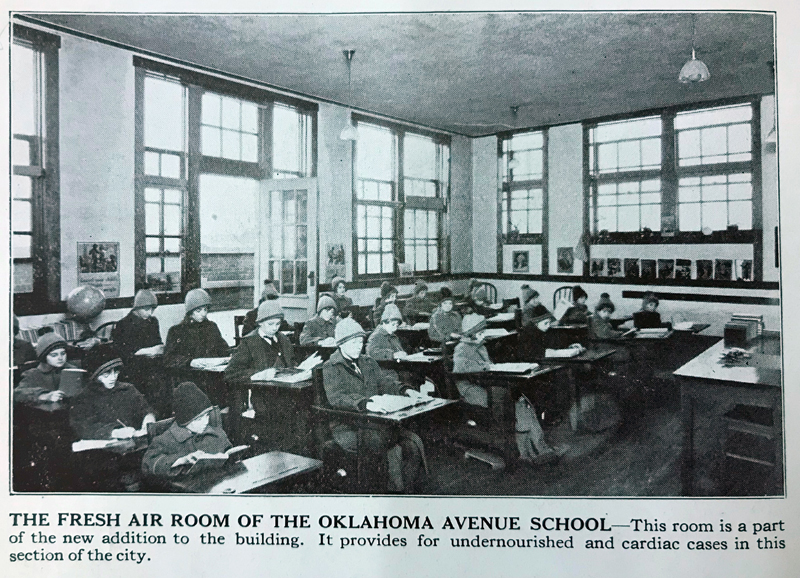

A 1921 newspaper article noted that the district also had an open-air facilities at Eugene Field and Lincoln Avenue Schools on the South Side. Oklahoma Avenue School also had a fresh-air room in the '20s.

In 1928, the school welcomed children with physical disabilities, too. Although 11 kids were at the school on its first day, enrollment was expected to be about 20 and the district provided transportation for them.

Nine years later, the school – which was educating kids who "needed open-air treatment" and those who had disabilities – was renamed Gaenslen.

Two years later, a new state of the art building, designed by Alexander Bauer of Eschweiler and Eschweiler Architects Associated, was erected along the Milwaukee River on a six-acre site between Burleigh Street and Auer Avenue in Riverwest.

The building's classroom wing overhung the riverbank, with views out across the river, and the riverfront property which had been designated as a bird sanctuary.

When the new Gaenslen building opened, it served a K-12 population and, according to a Wisconsin Architect article that appeared after the building's completion, "there are cases of infantile paralysis, spastic paralysis, or other birth injuries, cardiac difficulties, and accidental injuries. Anyone who anticipates a depressing sight, will be amazed at seeing these children ... They are probably the most cheerful group of pupils at any school in the city."

The unsigned February 1940 article describes the building, which was a single-story, variegated brick building with limestone trim, with an art deco flair, as having four functions: instructional, therapeutic, recreational and administrative.

"Many inquiries have already been turned over to the architects for information concerning the many unique innovations included in the design and plan of the new Gaenslen School."

Interestingly, Gaenslen's innovations may have helped render it outmoded at an early age. A year before the building would have celebrated its 50th anniversary, a replacement building – the current Gaenslen School – was completed.

"The old building may not have been that old compared to others in MPS' inventory of educational facilities," says Mark Zimmerman of Zimmerman Architectural Studios, which designed the current building, "but the needs and strategies had advanced that the old building was not as user-friendly with where the needs and the competition across the country were for these students with special needs."

Zimmerman, whose firm has designed a number of schools, says that there were many things to consider in designing Gaenslen.

"It was not a simple or typical tweak of a traditional school floor plan. Some of the drivers of the design were meeting a wide range of physically challenged students and their mode of mobility assistance, from wheel chairs, to wagons, to 'creepers,' but there was a full spectrum of mobility challenges and needs."

Because attitudes toward children with diverse needs have changed over the years, the approach to designing a school that serves those children has changed, too. There is perhaps an increased sensitivity not only to physical, but also to the emotional, needs.

"You add a want and need for equity and fairness," says Zimmerman. "Able-bodied students were an important part of the student population. They wanted to achieve a mix of mainstream students learning side by side with physically and mentally challenged students. So as not to call attention to the handicap, chalkboards, for instance, were built away from the wall so the knees didn't get jammed while a student completed a math problem at the board while seated in a wheel chair."

New teaching and learning methods also affected how educators envisioned a new Gaenslen School building.

"Teachers wanted flexibility to open up these fixed barriers from old traditional schools and teach in groups and teams," recalls Zimmerman. "Couple that with added space for maneuvering and access and the need for a new school was apparent. There were spaces programmed for therapy including hydro therapy, indoor play areas for rainy or snowy days with floor drains allowing for messy projects with hose-down clean-up capability was included, covered bus drop off areas.

"In the old school, the kids were let off one by one with a motorized platform that raised and lowered students very inefficiently and slowly. On a rainy or snowy day, these kids would be out in the elements getting wet and cold waiting to load or unload. Now they're at the same level as the bus floor and covered."

So, now that the current building is half the age its predecessor was when it was demolished and replaced, will advances in technology and changes in approaches to educating special needs students mean that Gaenslen School will need to be replaced in the next couple decades?

"Tough question," says Zimmerman. "I think we (as a society) have become somewhat of a disposable society. In the late '80s I was part of the Bradley Center design team. To hear talk of replacing it less than 24 years after it opened shocks me. But there is an embrace of sustainable design concepts and principles as well as environmentally responsible gestures like recycling old buildings/current buildings and finding adaptive reuses for architecture that once functioned to a different user.

"One thing that was visionary in Gaenslen was the moveable classroom walls which made the buildings and spaces adaptable, flexible and nimble. The test of time will be was it flexible enough? I probably wouldn't recognize a classroom today from when I was in school. With laptops, iPads, smart boards, and the like, the environments and the way children pay attention and learn are remarkably different."

Creating the current Gaenslen building was exciting, says Dave Stroik, Zimmerman's president and CEO.

"We did the school just as accessibility was becoming a hot topic, so it was fascinating to be on the bleeding edge. The new building was able to deal with many more issues of independence than the original such as projecting chalkboards that allowed real wheelchair access and a 'stimulation' room that blasted sound and light to underdeveloped senses of some of the students."

Stroik points out that while it wasn't possible to save the Eschweiler and Eschweiler building, he did make sure it lived on in some way in the new building.

"We incorporated some of the original art and the nursery rhyme friezes into the new building," he says. "But it was difficult to capture all of the intimate charm of the original school."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.