Few players get a chance to win multiple NBA championships, let alone one. Some can throw a bag of rings on a table; others lose track of time because there is no hardware, no inscription, to remind them of an anniversary.

Each applies to men who coached and played in the 1974 NBA Finals, seven games played over 15 spring days that has tied the Boston Celtics and Milwaukee Bucks together, forever.

On the 40th anniversary of that finals, OnMilwaukee.com takes you back – along with a dozen people affiliated with the series – to that classic, seven-game duel that featured six future Hall of Famers and an additional five All-Stars.

It's the history of that Finals as they know it, since no video exists of many of the games. The road team won five times, including the ultimate game – the first Game 7 of a Finals won by a visitor in NBA history.

"It’s got to stand out," said Celtics forward Don Nelson, who won five titles as a player and went on to coach the Bucks in the 1980s. "It was a great series."

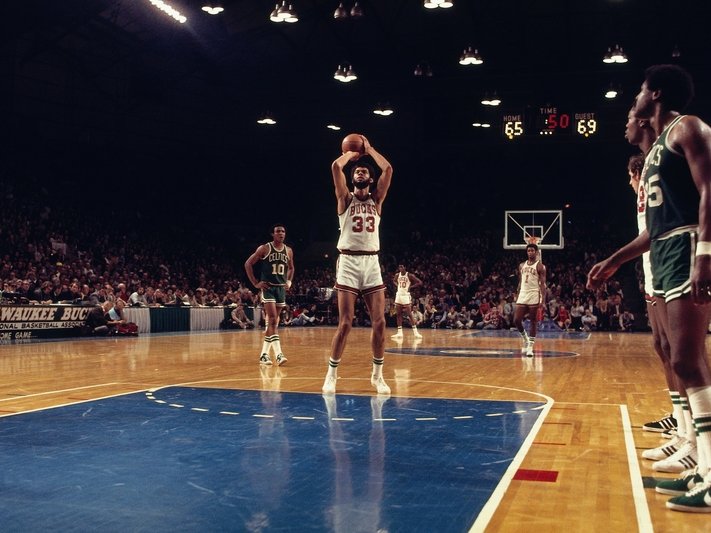

Milwaukee had the Most Valuable Player in Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and the legendary Oscar Robertson, who finished their fourth year together leading the league's best team.

"We were the David and they were the Goliath," Celtics head coach Tom Heinsohn said.

But Robertson, as well as other key contributors on the Bucks, were injured as they prepared to take on Boston, a team which had rebuilt with a 25-year-old center named Dave Cowens and was ready to reclaim its throne in the post-Bill Russell era.

But … "If you got a guy like Oscar Robertson and Kareem, no matter who you put out there you were going to have a good chance of winning," said Bucks reserve Dick Garrett. "That was kind of the mindset on this team.

"I don't think any of us thought we'd lose."

The lost games

The first five contests have been lost to time, even for those who lived them.

All can recall the intensity, the chess match between Bucks coach Larry Costello and Heinsohn, and the decision to harangue Robertson with a full court, man press while singling Abdul-Jabbar with Cowens. Without Allen, Heinsohn had wanted to take advantage of Don Chaney and Jo Jo White’s quickness in the backcourt.

It worked – the Celtics stole Game 1 98-83 at Milwaukee Arena, "The Mecca." The teams traded victories over the next four games, including a Bucks overtime triumph in Game 2 after the Celtics rallied back from a 14-point halftime deficit.

But no accessible video remains of those games – every player OnMilwaukee.com interviewed has never seen them. Even the family of former Bucks owner Jim Fitzgerald, who became a pioneer in cable television, has no tape of the CBS broadcasts.

"What I wish is that I'd like to be able to watch all seven games," Cowens lamented. "I wish somebody has the tape of all seven games. All you see is basically one game, the double overtime. And the final game, you see some clips from that. But what about game one through five? You don't really see too much of that.

"There were some good games."

There were – but ultimately they proved to be the table setters for an amazing three days in May.

Friday, May 10:

Game 6 at the Boston Garden

One of the most difficult environments to play on in the NBA welcomed the Bucks in Game 6. Bucks forward Bob Dandridge admitted the Celtics' gamesmanship played on the minds of opponents, like when an open window chilled the visitor locker room of the nearly 50-year old arena, and that the Celtics faithful could hang over the rails to welcome an opponent to the court.

This was where the Bucks, trailing three games to two, absolutely had to win to stay alive.

"Game 6 was one of the great games in NBA, not just Bucks, history," Bucks forward Jon McGlocklin said.

Milwaukee took an eight point first quarter lead, which was whittled to seven, then to six, after three quarters. The Celtics tied the game, but the Bucks had a chance to win at the end of regulation when McGlocklin set up on the left baseline and Robertson found him with three seconds left. His attempt, however, was short.

"Every time I jumped it felt like somebody stuck a knife in my calf," McGlocklin said. "I jumped off of one leg so it meant I was totally off balance. And I will guarantee you, had I been healthy that game would have ended right there."

Each team scored four points in the first extra session, and it was a putback by series MVP John Havlicek with five seconds left that sent the game into a second overtime.

Cowens then fouled out, which brought Hank Finkel off the bench to defend Abdul-Jabbar, but the Celtics looked to have clinched the title when Havlicek hit a baseline jumper over a closing Abdul-Jabbar with seven seconds left to give the Celtics a 101-100 lead.

Costello called for time.

He broke out his ever-present yellow legal pad and scribbled furiously, diagramming a half court set. Robertson would inbound, with Abdul-Jabbar, Davis, McGlocklin and Dandridge on the floor.

As Costello began marking players, they noticed Davis and McGlocklin were mentioned twice, in two different spots.

"Larry was kind of like, frantic, trying to think up a great play," Abdul-Jabbar said. "And, we just couldn’t figure it out all the way, who was supposed to get free."

Well, some were trying to figure it out – Dandridge wasn’t even paying attention.

"Everybody knew who was going to take the last shot, so in my mind there wasn't a need for a huddle!" Dandridge said. "I mean, you knew the ‘Big O’ or Kareem was going to take the last shot. So, everybody else just had to get out of the way."

The timeout ended, and Davis and McGlocklin asked each other what they were supposed to be doing.

"No one can remember what it was because no one really understood what it was!" Abdul-Jabbar said, laughing. "For all we know – I heard Jon McGlocklin’s name mentioned, and we have to do this, this, this. Then they were like, alright, we have to take the ball inbounds."

As for Dandridge?

"I was probably as far away from it as I could get because I didn't want my man to go in there and give any help on Kareem. I was somewhere between the top of the key and half court. For one thing, I didn't want the shot."

He belly laughed.

"I didn't want to be available for that shot."

Abdul-Jabbar cut across the lane, but he thought he was screening for McGlocklin. Instead, he broke up court to prevent a 5-second call and ended up with the ball.

"We did have a play," Robertson clarified with a chuckle. "You might call a play but in a basketball game the defense does something, so there are alternatives you're going to do and I had to catch Kareem open."

As precious seconds ticked away, and with no other option available, Abdul-Jabbar had to take it – even though Finkel had pushed him out to about 15 feet.

The long, awkwardly angled hook found the bottom of the net.

"I had no shot at blocking it because the hook shot is taken in outer space, you know?" Finkel said. "So I tried to push him a little farther out without fouling him, and that’s what I did, but he made it."

Paul Westphal, Nelson and Cowens were on the Celtics bench as Abdul-Jabbar evaded Chaney, who nearly stripped the ball.

"I think we played great defense and put him in a pretty tough spot and Kareem got the ball, turned and made a tremendous shot," Cowens said.

Nelson laughed. He couldn’t recall much from early in that game, but that shot?

"You see it all the time on the replays," he said. "They won’t let you forget that."

"I saw him make a lot of those sky hooks over my lifetime, between UCLA and his career in the pros with Milwaukee and the Lakers," added Westphal, who played against Abdul-Jabbar in college while at USC. "I’ve probably been on the receiving end of more of those sky hooks than almost anybody. That was deeper than most, though."

From his spot calling the game in the balcony, Bucks play-by-play man Eddie Doucette saw the chaos unfolding as a perfectly orchestrated symphony.

"It was just one fluid motion and it looked perfect to me," Doucette said. "And the way it turned out, it was perfect. So if there was confusion – I like to refer to the old adage – and that is where there is confusion there's opportunity, and the opportunity turned out to work out for the Bucks. It worked out the way it was supposed to."

In his office, Heinsohn and assistant coach John Killilea were licking their wounds. They were seven seconds away from a championship, and it was taken in an unlikely instant. Now the series shifted back to Milwaukee for the deciding game.

Celtics legend Bob Cousy, who had been fired earlier that year as the coach of the Kansas City-Omaha Kings, was in the Garden and made his way into Heinsohn’s office.

"Why don’t you double?" Cousy asked.

Heinsohn didn’t believe in that strategy, even on a player as dominant as Abdul-Jabbar. He didn’t see the point heading into the series – it didn’t work for everyone else, including Cousy’s Kings – all year long anyway. Abdul-Jabbar had developed into an excellent passer, and his teammates would find themselves at the rim with uncontested layups. Heinsohn believed constant pressure on Robertson was the best way to neutralize Abdul-Jabbar.

But as they rehashed what could have been, and prepared for what was coming in less than 48 hours at The Mecca, the idea of a double-team as a final move to end the game with Costello, resonated.

After all of Heinsohn's protestations about the idea, his sudden turnaround threw Cousy.

"Not because I believe the strategy will work," Heinsohn clarified. "But because I think it will cause a surprise and it will take a while for them to adjust, and maybe we can take the crowd out of the game in the first quarter."

Heinsohn was about to toss his defense out the window with no practice, shootaround or walkthrough to implement the new one. Despite the fact he had eight championship rings of his own as a player and 258 wins as a coach, he was nervous.

"This was a situation where if it didn’t work I might have been out of a job because the press being what it was – could a coach expect to change an entire defense in one day and play for the championship? What is he crazy?" Heinsohn admitted. "That’s the type of thing you were facing making a decision like that in one day. I had to really convince the players."

At Logan Airport, a worn Mickey Davis ran into CBS play-by-plan Pat Summerall as they waited to depart.

"What’s it going to be like tomorrow?" Summerall asked.

The teams alternated victories the last six games, the road team had won the last four, and two had gone to overtime.

"It’s truly anybody’s guess," Davis replied.

It didn’t take long for Summerall to add, "Boy, this is a fantastic series."

It struck Davis, who for the better part of two weeks had heard the same compliment from strangers in airports in Milwaukee and Boston – that he was living, playing, in one of the greatest NBA Finals to date.

"There was that vein, that type of thought that ran through everybody," Davis said.

That afternoon in Milwaukee, Heinsohn wanted to make sure it turned historic for Boston.

The Celtics didn’t practice on travel days, and they never had a shootaround. In a championship series where seven games were played over 15 days, it was just show up and play.

In a film session, Heinsohn pitched his idea. He had decided it would be the 6-foot, 7-inch Paul Silas who would leave his man and crash down on Abdul-Jabbar.

"We’re going to find out if Cornell Warner is a great player," Heinsohn said of the Bucks forward who would be left open.

Time would later bear out that five key players in this plan – Silas, Cowens, Nelson, Chaney and Westphal – would become NBA head coaches.

"To ask those guys to make an adjustment, that’s not that big of a leap," Westphal said of his teammates. "Those guys were real pros. It was a great idea by Tommy and for sure, it was an adjustment series and that was kind of the ultimate adjustment we hadn’t done yet and it was something that team could pull off. A lot of teams couldn’t but that team could."

"They recognized immediately this might work," Heinsohn said. "The idea was then to make Cornell Warner the hero of Milwaukee if he could adjust to the situation because he was the guy who going to be the given his opportunity to score. So, we gambled on that."

That night, in Milwaukee, the teams tried to rest as much as possible. An afternoon tip awaited.

"You should go back and ask the people in charge of scheduling those games, why did they do that?" Robertson said. "I'm sure the Celtics were in the same position we were in. They were tired and banged up, too."

Cowens began the day by pulling his own luggage down Kilbourn Ave. to the arena, a night after spending the night downtown visiting with family. His ease was symbolic: Boston felt little pressure.

There were butterflies, of course. A championship was on the line. The Arena was alive.

"Knowing that we had a better in season record and knowing going in what the home court advantage meant and knowing that we would get the last say, I had a strong feeling that we were going to win this thing," Doucette said, echoing the sentiments of many media, and assuredly the fans, in Milwaukee.

"We're going home. Enough of this losing on the home floor. It's gotta turn around, it's gotta break and maybe Sunday, with our fans and the enthusiasm and excitement, we could get it done."

Despite having already won twice in Milwaukee and armed with this defensive switch, the Bucks still had Abdul-Jabbar and Robertson.

"We were in big trouble," Nelson said. "We had to play a perfect game and everybody had to play extremely well to win."

In the home locker room, however, Goliath was wounded.

"We didn’t have a lot of confidence – you had confidence – but you knew but you knew you were limping in there on hope, to some degree," McGlocklin said. "But yet, we still had Kareem. Mickey Davis had done a great job. Bobby. Oscar was pulling his freight as best he could and we took ‘em to seven and we were at home. We didn’t see them dominating us.

"Going in, we certainly had hopes that we could win."

The ball was tipped and …

"It was total confusion," Heinsohn remembered fondly.

The double-team worked, as the Celtics broke the game open in the second quarter in stretching a 22-20 lead to 53-40 at the half. The Bucks rallied, briefly, in the second half before succumbing 102-87.

"The last game, I know I was tired," Abdul-Jabbar said. "I played two overtime games. It wasn’t there for us to win."

The league MVP finished 26 points, but on 10 of 21 shooting.

"The only way you could try – I stipulate the word try – the only way you could try to stop Kareem was by doubling him up," Finkel said. "No one man could stop Kareem. He was such a great shooter. He was a great offensive player. And being as tall as he was it made it that much more difficult to throw his shot off or block his shot, so the only way you could slow him down is to try to double team, and I think that’s what Coach Heinsohn had in mind at the time, and the perfect guy to double up is Silas. We knew we weren’t going to stop Kareem. Kareem was like Wilt (Chamberlain) – you don’t stop ‘em. But you try to slow ‘em down."

Heinsohn had won his match with Costello. Silas may well have yelled checkmate on his way to double Abdul-Jabbar.

"We had a forward who didn't even hardly score, or hardly play, so you call timeout and you try to get adjustments made – it's up to the coach to make the final decision," Robertson said. "Cornell Warner could not have been the hero of that situation because we didn't call on Cornell Warner to shoot the whole year, so why would we put all that pressure on him then? We should've put a shooter over there."

Warner scored one point, and took just three shots.

And with help for the first time, Cowens was unleashed.

"I thought Dave Cowens going into that third quarter was able to be as aggressive defensively against Kareem as anybody I've ever seen," Dandridge said.

Cowens was also making Abdul-Jabbar work defensively, never allowing for a breath a night after most on the Bucks believed their MVP played 50 minutes in Game 6. Cowens put up 25 shots and scored a game-high 28 points.

"Kareem was exhausted and we had nothing left," Doucette said. "No gas in the tank on that Sunday afternoon."

"We were flat," Davis added. "I’m not going to say … we certainly didn’t choke but I also think there was such a strong desire to do well at home in that seventh game I think, you know, maybe our muscles were a little tight in our shooting arms more so than they had been in the past. I don’t know. But I think anybody in their right mind would assume that type of pressure and stress would be greater at home, on the home team, then it would be on the visiting team. It’s easier to lose away than it is at home, obviously."

There was little celebration on the part of the Celtics, at least on court.

The Bucks looked around The Mecca, partly stunned, mostly fatigued.

"At the end of a series like that, you're just glad it's over," Dandridge said. "You know, you're like, OK, it's over, they won and you're exhausted and you know you laid everything out there so let's just go ahead and move on to the summer. It takes you, once you regain your juices and you've rested, then you reflect back on the pain of losing the game. For me, Boston won. They were the better team for that seven game series. Then it's over."

Robertson agreed, even though he, along with Garrett and McGlocklin, felt Costello could've utilized his bench more throughout the series.

"I would love to have won, but basketball to me is a game – you go out and give the best effort you can, they just had more baskets than we did at the end," Robertson said. "You can always say 'you should've done this or that' but we didn't."

Garrett, for one, was crestfallen. It was his second chance at a championship, having lost in seven games to the New York Knicks in 1970 while with the Los Angeles Lakers.

"If you’ve ever been an athlete and have had just played your heart out and played with everything that you had, and have a sense of just being sad about it," he said. "But at the same time you realize I’ve given it all I got and sometimes that’s all you can ask of a guy."

Unlike the other games from the series, game seven is accessible. Davis has a copy, and that’s good enough for him.

"I’ve never watched it," he said. "I’ve never gone back. People here will pull up YouTube, or wherever I worked pull up YouTube and I just never have and I don’t know why. That’s kind of how I think about. I tell people it was great just to be there."

Even for Bucks like Abdul-Jabbar and McGlocklin, who won the franchise's lone championship in 1971, it still stings.

"It’s very frustrating because if we were healthy, I think we would have beat them in six games," Abdul-Jabbar said. "If we had Oscar (full strength) and Lucius (Allen), because they were our perimeter guys. Lucius was a great shot, especially he if could get that wide open jump shot right around the free throw line, that’s a backbreaker. We just didn’t have the depth to match them coming off the bench."

"That one would have been really pleasing because it would have been the second time and you had to work so hard for it and you could see it out in front of you so far (away) whereas in ‘71 it was boom, and wonderful, magical," McGlocklin added. "But ‘74, that was labor. And we all would’ve loved it, you know? You don’t have fond memories of it, no. Nope."

The championship was Boston’s first in the post-Russell era, and they would win another in 1976.

"It was a very special series because it was Dave Cowens’ first championship and I’m sure it was Westy’s as well," Nelson said. "You win 11 out of 1(3) and then Russell retires and nobody expects much of you but we were in the championship games several years later. Yeah, it was a big deal for that squad without Bill Russell."

For the Bucks, however, 1974 would prove to be the end of an era.

Robertson retired after 14 seasons. Abdul-Jabbar would play one more year in Milwaukee before being traded to Los Angeles.

"I think we all knew it had a shelf life, but it’s not something you discussed," McGlocklin said.

McGlocklin called it the Golden Era for the franchise, but it's one that carries a tint of regret for many.

"We lose the game, we lose the series, we lost the chance, but like Oscar (has) said, we should've probably had three, four rings during that period," Doucette said.

Milwaukee has yet to reach another NBA Finals.

May 10: Postgame

Saturday, May 11

Sunday, May 12:

Game 7 at the Milwaukee ArenaEpilogue

Jim Owczarski is an award-winning sports journalist and comes to Milwaukee by way of the Chicago Sun-Times Media Network.

A three-year Wisconsin resident who has considered Milwaukee a second home for the better part of seven years, he brings to the market experience covering nearly all major and college sports.

To this point in his career, he has been awarded six national Associated Press Sports Editors awards for investigative reporting, feature writing, breaking news and projects. He is also a four-time nominee for the prestigious Peter J. Lisagor Awards for Exemplary Journalism, presented by the Chicago Headline Club, and is a two-time winner for Best Sports Story. He has also won numerous other Illinois Press Association, Illinois Associated Press and Northern Illinois Newspaper Association awards.

Jim's career started in earnest as a North Central College (Naperville, Ill.) senior in 2002 when he received a Richter Fellowship to cover the Chicago White Sox in spring training. He was hired by the Naperville Sun in 2003 and moved on to the Aurora Beacon News in 2007 before joining OnMilwaukee.com.

In that time, he has covered the events, news and personalities that make up the PGA Tour, LPGA Tour, Major League Baseball, the National Football League, the National Hockey League, NCAA football, baseball and men's and women's basketball as well as boxing, mixed martial arts and various U.S. Olympic teams.

Golf aficionados who venture into Illinois have also read Jim in GOLF Chicago Magazine as well as the Chicago District Golfer and Illinois Golfer magazines.