Like Ryan Braun, Charley Parham was a prodigious slugger whose career ran afoul of his own lies and a chemical substance. In the case of Parham, an exciting, popular middleweight boxer in the mid-1940s, the latter was not a steroid but a truth serum administered to Parham by order of the Milwaukee County District Attorney.

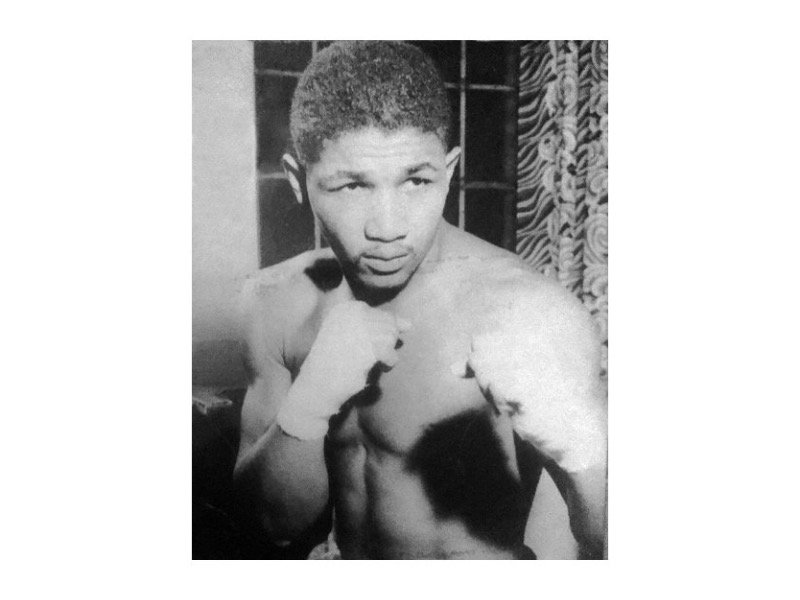

A Golden Gloves champion in his native Detroit, Parham came to Milwaukee around 1941 when pro boxing was enjoying a local resurgence. The 5-foot, 3-inch Parham ramped up that process by knocking out six straight opponents in such spectacular fashion that he picked up two nicknames: "Chiller Charley" and "The Mayhem Man."

When Parham landed a punch the other guy usually took a 10-second nap. When he missed, as happened just as frequently, the centrifugal force of the swing often sent Parham sprawling on the canvas himself.

Slick boxers like welterweight contender Cecil Hudson jabbed him silly, and in the biggest fight of his career, on Dec. 7, 1945, future middleweight champion Jake LaMotta went Pearl Harbor on Parham at Chicago Stadium because the Milwaukee fighter (who’d earlier that year won the state welterweight title by knocking out previously un-knockoutable Savior Canadeo at the Auditorium) entered the ring almost paralyzed with fear of "The Bronx Bull." Too chilled to fight, Parham was knocked down in every round until the referee stopped it in the sixth.

Outside of the ring, Parham – a high school dropout whose mother was 13 when he was born – was as unsophisticated, impressionable and audacious as a child. He signed anything put in front of him, which led to frequent court actions brought by a dizzying swarm of managers and promoters brandishing "exclusive" contracts bearing Charley’s signature. As soon as the judge straightened things out, Parham went out and signed a new raft of conflicting contracts.

According to The Ring magazine, The Mayhem Man was "so religious he’s never without the Bible"; and Parham himself once proclaimed, "Honesty is my motto." But Milwaukee Journal sports editor R.G. Lynch called him "the most wanton liar in this reporter’s experience."

"If Parham actually saw a robber run out of a bank, gun in one hand and money in the other, and identified the man positively, it would be impossible to convict the man on that testimony," wrote Lynch.

Charley didn’t lie maliciously. In the case of all those contracts, Parham told a judge, he hadn’t bothered to even read them but signed because "I didn’t want any more aggravation."

Charley fancied himself as good a singer as he was a puncher, and that actually wasn’t as big a stretch as some of his other claims. Crooning in, as he put it, "the key of Frank Sinatra," the Chiller performed in nightclubs in Milwaukee’s historic Bronzeville neighborhood whose epicenter was W. Walnut St.

The day after jazz icon Lionel Hampton and his orchestra played here on June 18, 1945, there was a picture in the newspaper of a stylishly double-breasted, pinstriped Parham singing on the Riverside Theater stage next to Hampton.

But it was the singing Parham did after he won a 10-round decision over Art Brown of Chicago on Sept. 17, 1946, that won him his greatest notoriety.

In his dressing room at the Auditorium Charley said that several days earlier he was offered $1,000 by a local saloonkeeper named Harry Klein to go into the tank – i.e. lose on purpose – against Brown.

When District Attorney William McCawley issued a warrant for Klein’s arrest the next day, Parham recanted, saying he’d made up the story about the bribe attempt because "I wanted publicity. The truth is the big thing in my life. I’m ready to go to jail if necessary for telling a lie yesterday. I’m all through as a fighter. I have plans of being a singer now."

McCawley took the unprecedented step of having Parham taken to County Hospital and injected by a doctor with sodium amatol, commonly known as truth serum. The result was as wild as one of the Chiller’s fights. As the truth serum started to enter his bloodstream, Parham went back to his first story, claiming Klein had tried to bribe him and saying he had refused for "the honor and glory of Wisconsin."

Later, however, coming out of the deep sleep induced by the serum, Parham called that version "a dastardly and uncouth lie" he’d told "just for the fun of it" and because "it would look nice in the papers, (which) have lots of space to waste printing stories like that."

"I lie an awful lot," he said. "I lie habitually and profusely, but I am not a pathological liar. I don’t know why I lie so much. They tell me I lack mental stability, but there is nothing abnormal about me."

Four more times in the course of the session, Parham denied the attempted bribe, and at one point whined, "I wanna go home to my momma."

He went to the county jail, instead, and the next morning Charley met with D.A. McCawley and, incredibly, reversed himself once more. He’d told the truth the first time, he informed the D.A. – Klein had tried to bribe him to throw the fight.

The thoroughly flummoxed McCawley threw up his hands and issued a statement to the press:

"Charles Parham was ordered released today by me and the warrant against Harold Klein is withdrawn for the reason I have exhausted every means of arriving at the truth. I am satisfied Parham is in such a confused state of mind his word is not dependable and no conviction could result from any prosecution based upon Parham’s conflicting stories."

After a two-month suspension imposed by the state athletic commission for "actions detrimental and injurious to boxing in Wisconsin," Parham resumed boxing until it was discovered that he was half-blind – hence those flagrant wild swings – and his license was yanked for good, albeit with great reluctance on the part of some of the boxing commissioners.

"He’s been fighting for five years, so why bring up his eyesight now?" groused one. Another said it was a shame to bar him because fight fans wanted to see Parham fight "even if Charley has to be led into the ring."

Broke and sick, Parham died in a north side nursing home in 1970, at 42. The obits were surprisingly kind, not even mentioning the episode that was front-page news 26 years earlier and instead highlighting his uber-exciting efforts in the ring.

The latest most wanton liar in Milwaukee sports should be so lucky.