"A fat English Pug meets a long, lean dachshund on a street corner," joked the Milwaukee Journal in 1938. "'Good gracious, you’ve certainly reduced!' said the Pug. The dachshund responds, 'Three weeks ago, I was sold to a vegetarian.'"

Milwaukee was a strange place to find vegetarians in 1938. True, vegetarians had existed for thousands of years, dating back to Plato and Plutarch, but the meatless diet was always a hard sell in the Dairy State. Newspaper reports spoke of strange gourmet restaurants in London and New York where patrons dined only on flowers, grasses and dirt.

Local "vegetable health" cafes had come and gone, including the Vegetarian Cafeteria (759 N. Water St.) which beckoned, "Don’t judge a vegetarian meal by hearsay ... discover how really delicious and healthful our scientific food can be!"

Milwaukeeans scoffed at these short-lived ventures. Vegetarians were seen as curious creatures, believed to spend most of their time starving. They were eyed as suspiciously as someone who claimed not to drink or smoke. Meat was a symbol of prosperity, luxury, hospitality and good health. Going meatless was un-American; after all, Adolph Hitler was the era’s most well-known vegetarian.

Knowing that, who would choose not to eat meat?

Henry Lightfoot Nunn, that’s who. As the president of Nunn Bush Shoe Company, Henry L. Nunn (1878-1972) had won over the workforce with the state’s first annual pay plan in 1935, which guaranteed 48 weekly paychecks per year regardless of actual production.

Beloved, respected and idolized as a benevolent business leader, Nunn surprised everyone when he came out as a vegetarian in 1916. "With Henry Nunn, vegetarianism is not a means to health or a way to keep slim," commented the Milwaukee Sentinel. "It is a religion."

Sickly his entire life, Nunn went vegetarian at age 38. His health improved so dramatically that he became a national advocate for the meatless lifestyle, influencing friends and family members to do the same.

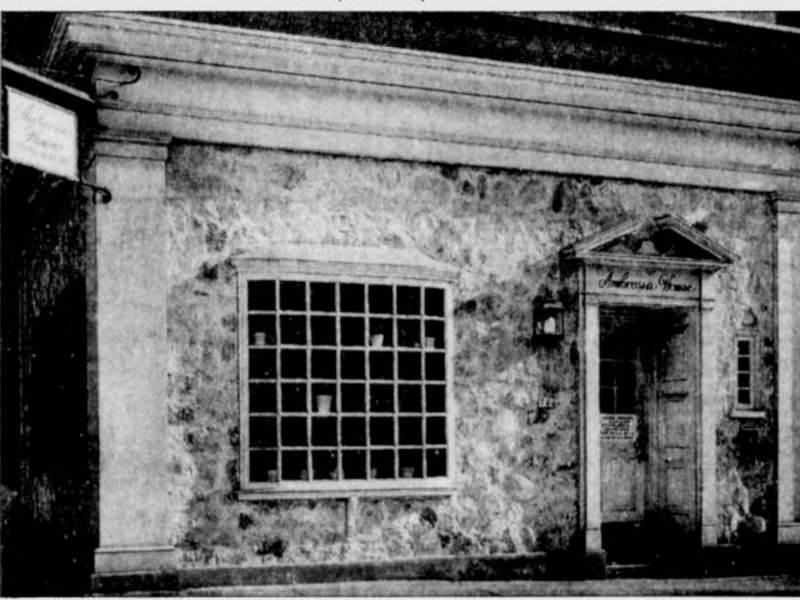

Visiting guests often told Nunn that if there was anywhere to buy meals like those he served in his own home, they would become vegetarians too. In fall 1938, Nunn decided to make that possible by opening Milwaukee’s first full-service vegetarian restaurant, the Ambrosia House (744 N. Jefferson St.).

(PHOTO: Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

(PHOTO: Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

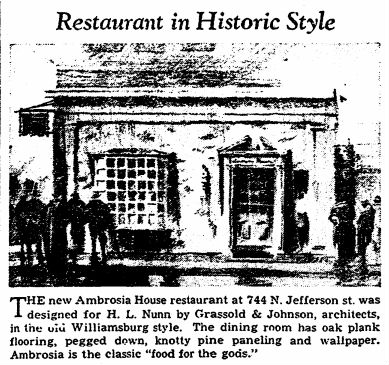

"Upon his Temple of Taste, Mr. Nunn will spend thousands to reincarnate an old edifice in the style and atmosphere of those early American buildings Mr. Rockefeller has reconstructed at Williamsburg, Virginia," said the Milwaukee Journal on Sept. 18, 1938. Milwaukee architects Grassold & Johnson, from a nearby firm, were contracted to complete the build.

"At the Ambrosia House, neither fish, flesh nor fowl will be served, but this restaurant will have no other semblance to ordinary vegetable health restaurants. The food will be salted, peppered, spiced ... tasty, not tasteless. Ambrosia is defined as food for the gods."

With carved flagstone exteriors, hand-hewn timber ceilings, knotty pine paneled walls, barnwood plank floors, a hand-carved oak bar and a forever-roaring fireplace, the tiny little stone cottage was quite an architectural sight in the Teutonic Milwaukee of 1938. Still, most customers just raised their eyebrows at the Ambrosia House and mumbled "maybe."

Admittedly, the original menu didn’t win rave reviews. Raw mushroom cocktail? Nut loaf? Brewer’s yeast soup? Nothing was right. Nunn recruited his niece, Caroline Sweeney, for a mission: travel the country, sample vegetarian recipes from America’s top chefs and bring only the best back to the Ambrosia House.

Caroline was remarkably successful in that mission. As a dietician trained at Battle Creek College, Caroline pledged that only fresh fruits and vegetables would be used – never frozen. She promised to introduce Milwaukee to international spices and seasonings never before tasted in the region. Within months, the restaurant became the most popular gathering spot in East Town. In August 1939, the Ambrosia House doubled capacity to 125 customers by adding a basement snack room serving desserts, a Huckleberry Finn dining room reserved for men only and a remodeled main floor dining room.

(PHOTO: Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

(PHOTO: Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

At long last, the rave reviews started to roll in. And they just kept coming.

"On the block of Jefferson at Mason, just a block north of the Post Office, is the Ambrosia House, somewhere unusual and unusually good," said the Milwaukee Journal food critic in August 1943. "The atmosphere is quiet, peaceful and quaint. The food is of the home cooked style, served in generous portions by young women of refinement. No flesh foods of any kind are served. Housewives troubled by the current meat shortage will find the Ambrosia House a treasure house of ideas for tempting vegetarian dishes. Truly fine dining at truly low prices."

The columnist wasn’t kidding. Complete luncheons, consisting of a sandwich, salad, cake and beverage, were offered for just 30 cents until the end of World War II. The restaurant served three meals a day, starting with famous hot cinnamon rolls every morning for five cents apiece.

With esteemed East Town company, including the Pfister Hotel, Watts Tea Shop, the Layton Gallery of Art, T.A. Chapman’s, and a busy shopping district, the Ambrosia House became the place for ladies who lunch. It was the scene of high teas, fraternity reunions, sheepshead leagues, holiday dinners, political rallies, bridge clubs, business meetings, wedding receptions and family reunions. The Ambrosia House created new traditions, including Founder’s Day dinners, 4th of July parties and, of course, Lenten dinners every Easter. Many Milwaukee children remember the Ambrosia House as one of the first Downtown restaurants to offer free crayons and coloring placemats.

Caroline expertly managed the day-to-day operation, and eventually the Ambrosia House just became known as "Caroline’s." The restaurant welcomed celebrity guests, including Gloria Swanson, Jeannette MacDonald and Helen Hayes, as well as vegetarian chefs from around the globe. Later, Caroline’s sister Julia joined the business. The sisters appeared on local TV and radio shows to promote healthy living options. From 1949 to 1954, the sisters also ran a dessert lounge next door at 740 N. Jefferson that was known nationwide for its incomparable Baked Alaska and superb Schaum Torte.

Neither Caroline nor Julia ever married. After their uncle retired to La Jolla, California in 1950, the Sweeney sisters were left in Milwaukee with many friends and customers, but few relatives. Homesick for their extended family in Breckenridge, Texas, the sisters decided to exit the business in 1956.

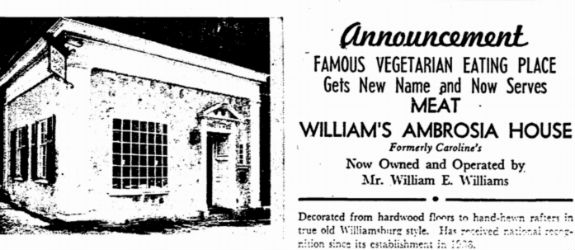

"For the first time in 18 years, meat dishes will be served at the Ambrosia House," read the Milwaukee Journal on March 7, 1956. New owner William E. Williams, proprietor of the Williams Cafeteria at 629 N. Broadway, vowed to maintain some of the vegetarian specialties, but felt that the restaurant could not compete without meat or fish entrees.

(PHOTO: Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

(PHOTO: Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

"The building will retain its Williamsburg atmosphere, and the name plate of William’s Ambrosia House," said the new owner, "but the most famous vegetarian eating spot in Milwaukee has become a thing of the past."

The gods did not smile on this hubris. Milwaukee’s finer restaurants had already added vegetarian entrees, so adding non-vegetarian options to the Ambrosia House did nothing more than level the playing field in favor of the competition. No longer a unique experience, William’s Ambrosia House closed sometime in 1959.

Later that year, restaurateur Otto Schuler took over the business and changed the name to the Seaway Inn. Commemorating the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway, the Seaway Inn blended the Early American theme with a nautical look and feel. It also became one of Milwaukee’s most popular gay bars of its era, especially after The Columns opened at the Pfister Hotel in 1960.

As a contributor to the Wisconsin LGBT History Project remembered, "The Seaway was a very cozy little bar, and rather good restaurant, where conversations would stop whenever someone stepped in. There were maybe 20 stools in the entire place and usually a roaring, crackling fire. It was dark, woody and smoky, but the lights and the smell were just right."

Otto Schuler went all out for the Seaway’s "Christmas in July" parties, which were as famous as they were infamous. People attending Downtown 4th of July fireworks and parades would often stop at the Seaway for their one-and-only annual visit.

For a while, two very different Seaway Inns operated in Milwaukee. Imagine the hijinks that ensued when patrons accidentally visited the other Seaway Inn of the 1960s (525 S. Water St.) that served as the official headquarters for the Outlaws motorcycle club. The bar, deemed "filthy" and "obscene" by City of Milwaukee officials, lost its license in 1966, putting an end to any confusion.

Few of the Seaway’s patrons knew or cared about its past lives, but most assumed the building to be an irreplaceable historic landmark. Since the old stone cottage only dated back to 1938, not colonial times, the city of Milwaukee didn’t exactly agree. The block was increasingly targeted as an ideal location for surface parking.

In December 1969, the East Town Association hosted a rally to save the Seaway and 36 other businesses from planned demolition. "In case you didn’t know it, that roof above your head will be razed," said Robert Aronin, association president. "The whole nature of East Town is threatened by tearing down one of its most interesting blocks." The battle raged on and on, while the Seaway’s neighbors were razed one by one, leaving behind a lonely stone cottage in a sea of surface parking.

After one last "Christmas in July" party, the Seaway closed in 1971. The building was razed in 1972. Ironically, Milwaukee’s most famous vegetarian restaurant was torn down – and founder Henry L. Nunn passed away at age 94 – just as the publication of Frances Moore Lappe’s "Diet for a Small Planet" was sparking new national interest in a vegetarian movement.

After relocating his bar to 173 S. 2nd St., and opening New Jamie’s Bar at 196 S. 2nd St., Otto Schuler died suddenly in November of 1973 at age 49. Caroline Sweeney (1909-1990) became a highly successful children’s department buyer at Neiman Marcus in Dallas. Her sister, Julia (1927-2011) worked her way up from the Neiman Marcus PR department and became a famous society columnist for the Dallas Time Herald. Both sisters reflected frequently on their remarkable experiences in Milwaukee.

Today, there are 7.3 million vegetarians in the United States, twice as many as surveyed a decade ago. Although Americans eat more meat than almost any country on the planet, consumption has dropped off in recent years. Vegetarian options now appear on almost every restaurant menu in Milwaukee, with many restaurants specializing in vegetarian and vegan fare.

Although there isn’t much groundbreaking at Jefferson and Mason today, the groundbreaking legacy of the Ambrosia House has never been more alive in Milwaukee.