"The New York fight mob includes a ready supply of behind-the-scenes managers capable of ordering or executing a murder. The most notorious is Frank Carbo ... Robert K. Christenberry, chairman of the New York Athletic Commission, revealed that Carbo and his henchmen influence the fate of perhaps two-thirds of the fighters importantly active today. Christenberry also added that Carbo and his mob or their stand-ins do business with the legitimate promoters of boxing ..."

The above quote and other excerpts from an expose published in LOOK magazine appeared in a column by Lloyd Larson, editor of the Milwaukee Sentinel, on Jan. 17, 1954. For most of that decade, Frankie Carbo controlled and operated professional boxing like his own private chessboard, deciding which fighters won titles and prearranging results of fights to guarantee the biggest financial score (for himself and his stooges, not the boxers). In 1958 he went to the clink for his crimes.

Exactly one week after the above-mentioned column ran, Larson wrote one about a fight happening the next evening, Jan. 25, at the Milwaukee Arena. The 12-round main event for the middleweight championship of Wisconsin was between Milwaukee's Ted Olla and Al Andrews, who was born and raised in Oliver, a village eight miles south of Superior.

Larson hyped the fight as "a throwback to the old and happier pugilistic days when Milwaukee crowds were treated to real contests," and even more so because the promoter – a "sucker for a left when the magic word charity is mentioned" – had promised that $1,000 from the live gate would be donated to the March of Dimes "even if the show loses money and I have to dig into my own pocket." (Which, by the way, he did.)

"Drives having to do with polio, cancer and other dread diseases are close to my heart," the promoter told Larson. "I believe in them and I'll stick with them. That goes even if nobody helps."

"Solid attitude, don't you think?" asked Larson at the end of his column - probably the last time anybody in the Milwaukee media said that about Frank Balistrieri, who seven years later became the don of the Midwestern mafia and eventually did his own prison stretch for his transgressions as Milwaukee's Godfather.

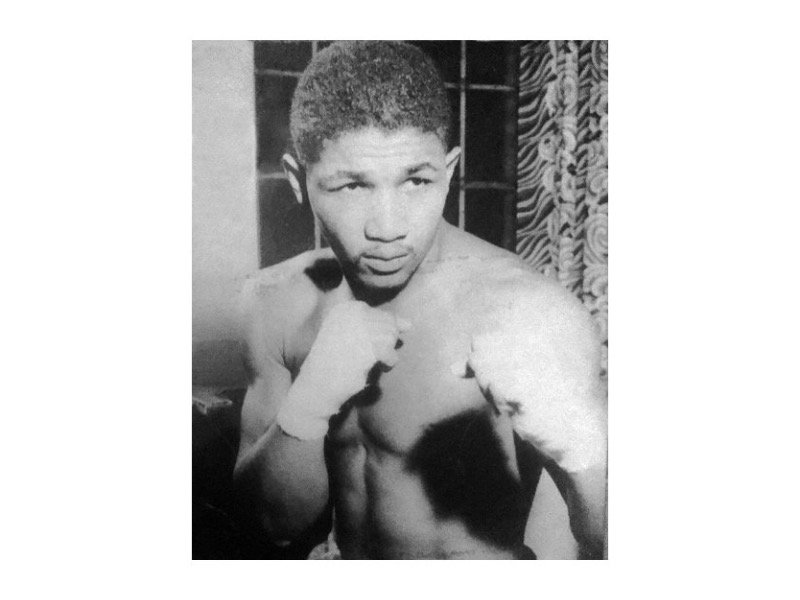

All this comes to mind with the belated news of Al Andrews' death in a Mellen, Wisconsin nursing home three days before Christmas, at age 81.

Born July 17, 1931, Andrews learned how to box growing up in Oliver with his seven brothers in a house that didn't have indoor plumbing. They carried water in by the bucketful from a well and the nearby St. Louis River. Al also learned how to play the accordion, and as boy he performed at area weddings.

He quit high school at 17, joined the military and won the Fifth Army middleweight title. But when he was discharged in 1952 the plan was to play his accordion for a living, until a member of his musical trio drowned in an accident. Then Andrews decided to ditch the squeezebox and go with his other specialty – making chin music with his fists.

"I was a young guy and I needed money," he told me in a 1995 interview, "and that was the fastest way I knew how to make it."

He won all but four of his first 31 bouts, including a pair of decisions over Chuck Davey. Davey was the Golden Boy of professional boxing when fights sponsored by Pabst Blue Ribbon and other advertisers were broadcast in primetime three times a week by the national TV networks. With his blond good looks and fast hands, Andrews fought on the tube more than 20 times in boxing's first and most popular television era.

Two weeks before he fought Olla in Milwaukee, Andrews won his first bout in New York and wowed the cynical Gotham boxing press. "He fights like a throwback to the glory days of fisticuffs," enthused Caswell Adams.

Andrews recalled the Olla fight as one of the easiest of his 91-bout career. "I won 12 out of 12 rounds," he said, recalling that after the last bell even Olla – an honorable bruiser – told him, "You won the fight."

But the judges saw it otherwise and awarded the decision to Olla.

In his nine-year ring career there were other questionable decisions against Andrews. He lost to Joey Giardello, Gene Fullmer, Denny Moyer and Jose Torres – all future world champions. But as the onetime Lawrence Welk wannabe who fought only three times in his home state put it, "When you fight in somebody's backyard, you dance to the hometown band."

Andrews' biggest televised fight was at Chicago Stadium on Sept. 29, 1954. Normally not a heavy puncher, he spectacularly flattened welterweight contender Gil Turner in the third round, for which Al credited giving up his two-pack-a-day cigarette addiction for a month instead sticking to his usual routine of cutting down to half-a-pack on the day of a fight.

Not smoking for a month "pretty near killed me," remembered Andrews. "I really suffered. I got so much pressure in my body, I couldn't believe it."

Neither could Turner, who was out cold for five minutes. The only mistake Andrews made that night was celebrating by falling off the wagon. "I grabbed one (cigarette) and was hooked right back again. If it hadn't been for cigarettes, I could've become champion of the world."

Andrews stayed in the ring too long, fighting even after incurring neurological damage. But he didn't regret it.

"Boxing's a hell of a sport," he said in 1999. "If I could do it all over again, I'd be the same guy, do the same thing. I'd just throw the cigarettes away."

His biggest purse was just $5,000, but Andrews did achieve one of his goals. He had running water and a toilet installed in the house in Oliver.

"Those were things my mother never had," said the tough guy whose boxing career was as noble and praiseworthy as Frankie Carbo's was not. "I loved my mother."